The Story of Atelier de Chronométrie

Kwan Ann Tan

If you have ever visited Barcelona and walked through the heart of the city, past its historic streets and Gaudí-designed architecture, you may have unknowingly wandered past the building that houses the Atelier de Chronométrie workshop. Nestled in an early 19th-century structure, complete with ornate iron and stone balconies, this is where the past – specifically the spirit of the 1930s and 40s – is kept alive.

Founded by Santiago Martínez and Montse Gimeno in 2016, Atelier de Chronométrie has gained a steady cult following over the past nine years. They are known for their adherence to classic case sizes and vintage-inspired designs, with a strong dedication to handmade parts in traditional styles and colourful variations. While they have retained a small core team of just three people today, they also work alongside a network of collaborators, local artisans, and suppliers. Their small size explains why their business model is geared towards extremely limited releases and a high level of customisability.

However, despite being a smaller independent brand located away from Switzerland, their output so far is impressive, having produced two watches (the AdC 21 and 30) for Only Watch auctions, and collaborated with reputed international retailers such as Japan-based Shellman. A strong spirit of independence permeates their culture, as they have continued to keep their workshop small and refused to take on investors, relying instead on their network of clients and moving in a direction driven by their own desires. We explore the story of how Atelier de Chronométrie came to be, some notable examples in their catalogue, and what’s next in store on their journey.

From Dealers to Makers

Martínez and Gimeno first made their entry to the watch world through dealing in vintage pieces. Their first enterprise, Mimandcroket, was founded in 2009 and remains active to this day. Their appreciation stemmed from a love of classic, timeless watches that still strongly appeal to today’s collectors. The duo’s interest only grew the more they were absorbed into this world, as part of the trade involved rigorous study to gain an intimate familiarity with the history and background of these watches.

As Gimeno explains, “We started off as dealers of vintage Patek Philippe. Our background as vintage dealers has helped [with Atelier de Chronométrie] because for 15 years, we saw the best calibres in the world. For us this was the best inspiration, to just open a caseback.

“Being independent gives us the freedom to create the designs we want and not be conditioned by the market. If we have to say no to someone, we say no to someone. We want to focus on the product, and the product is the result of our hard work.”

“In the past, the movement was only for the eyes of the watchmakers, not for the people. It’s always incredible to open a caseback and see a magnificent movement, made in the 30s or 40s by skilled watchmakers, with incredible finishing. This was a big inspiration for the design [for Atelier de Chronométrie] because the designs of the watches in the past were amazing, with crazy dials, incredible combinations and colours, cases, with different types of lugs.”

While not many vintage dealers make the jump to creating their own watches, it was a natural next step for them to create Atelier de Chronométrie, partly because of Martínez’s background as a designer who worked in the fashion industry for almost 13 years.

“The idea for the Atelier de Chronométrie came about in a very natural way,” Gimeno says. “We didn’t have any special intentions to create something like that, but Santi has always been a very creative person. We decided to create a watch that was technically and aesthetically beautiful. The idea was to create a super-classic watch. Nothing strange. Simple, timeless, and with a small case.”

Vintage Made Modern

The team today (Left to Right): Watchmaker Pierre Aubert, Martínez and Gimeno.

And just like that – the two established Atelier de Chronométrie in 2016. It was clear that vintage was always going to be the inspiration, given the founders’ background, but also that they would stick as closely as possible to classic aesthetics and styles, with the added bonus of customisability. In essence, they offered the rare proposition of creating the vintage watch of their and their clients’ dreams, powered by refurbished and improved vintage calibres suited to the style.

The team back then was equally small, consisting of just Martínez, Gimeno, and the watchmaker Moebius Rassmman, who had some experience with the Omega 266 calibre used in the early AdC watches from making his first watch, although he is no longer affiliated with the team today.

“For us, the best example is the Patek Philippe Ref. 96,” Martínez says, when asked about early inspirations for the first AdC watches. “It has the perfect [case design]. It’s quite small at just 30.5mm, but it has a lot of presence on the wrist, and the variety of dials is amazing. Crazy sector dials, diamond dials, Breguet numerals, etc. I think it’s our favourite reference.”

Gimeno adds, “We just wanted to make classic, clean pieces, that [don’t follow] a special moment of fashion or period, but something that can live forever and can be with you forever, because they never get old-fashioned. That was the idea.”

They were not only inspired by vintage designs and aesthetics, but also by the spirit of the period itself, with a stronger emphasis on close relationships between the maker and collector, which led them to create limited or customisable pieces. The idea of history and artisanal craft permeates their way of thinking. Gimeno says, “We were inspired by the type of relationship between artisans and customers that was more common in the past compared to now. We wanted to replicate that feeling, especially because each customer is a different person, our relationship with them is very different, and each watch has its own history.”

However, it was not necessarily all smooth sailing. “Making watches is very different [to dealing in them],” Gimeno says. “We realised it is more difficult to produce something than just to buy and sell. We have problems with the production of the watch, the delays with the supplier, technical problems, etc.

“Our philosophy makes things even more complicated because we want to create something unique each time. So it’s even more difficult than just making a repetitive product. But we try to apply the same strategy as with our vintage watches, where we prefer to buy less and find those of good quality. With our watches, we prefer not to have a big production, but to make very high quality, unique pieces. It’s the same strategy applied to two different types of businesses. And there is some connection between them because the vintage inspiration that Santi has in his mind is put into the Atelier watches. But without any doubt, they are very different businesses.”

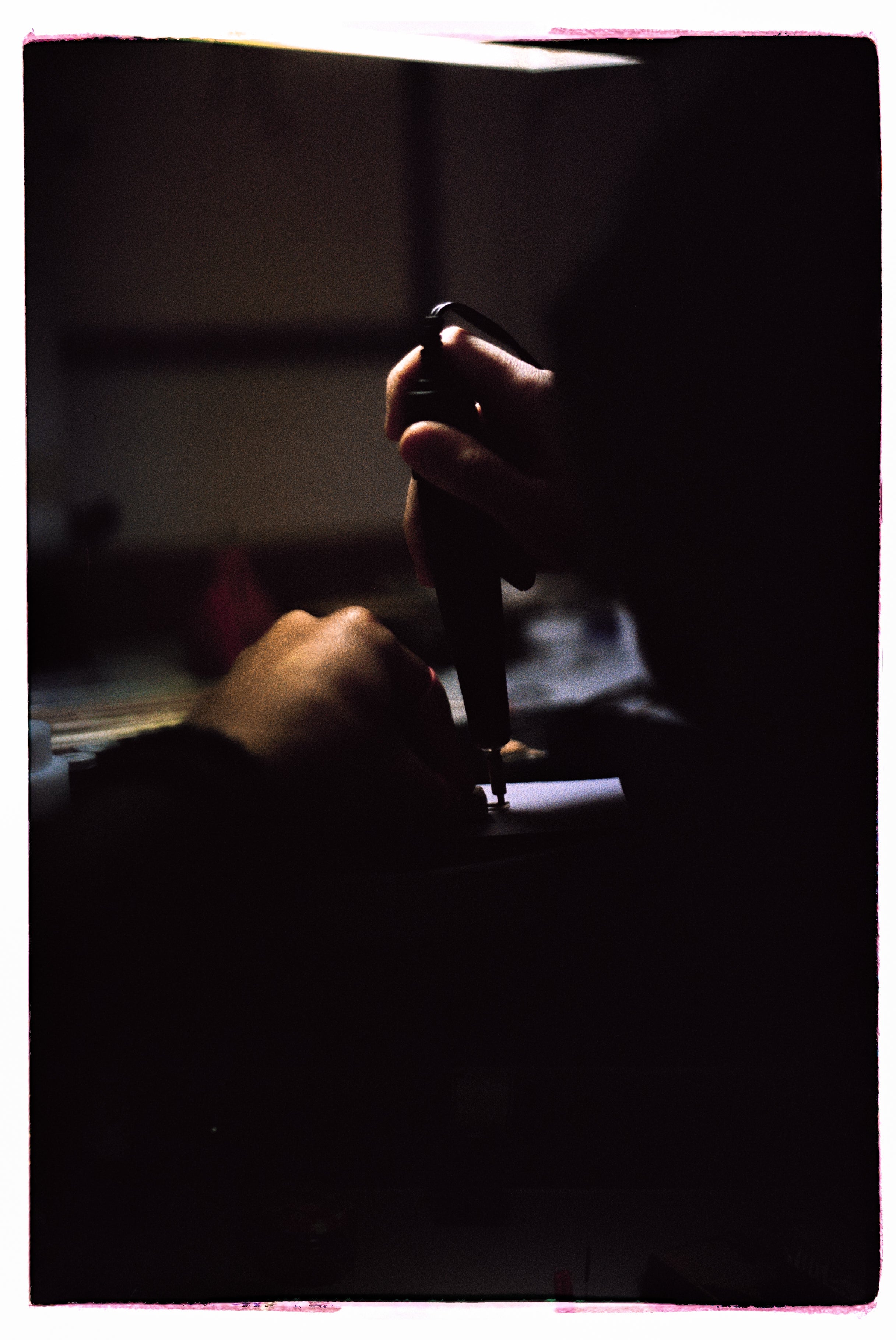

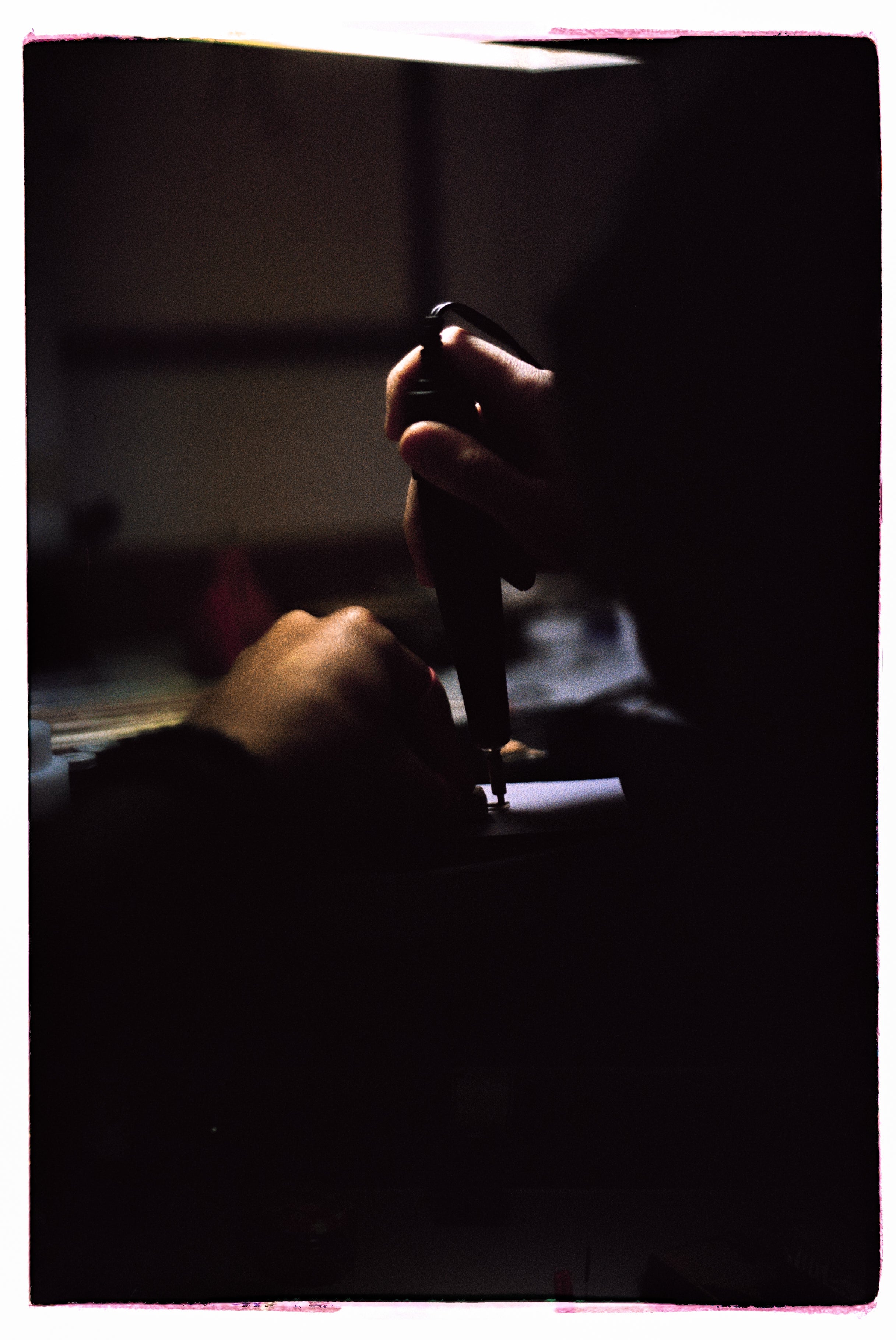

A glimpse into the case making process – deciding diameters and finishes.

Furthermore, back in 2015 when the trend was mostly geared towards large and larger watches anywhere from 42 to 44mm, with some of the largest hitting 50mm, their idea was met with some resistance when it came to the case size. As Martínez recounts, he spoke to collectors who commented that the 37.5mm diameter seemed more like these were watches specifically for women. However, this early feedback did not deter the Atelier de Chronométrie team, as they were already going against the grain by recreating vintage styles rather than simply being inspired by them, and never intended on having mass-market appeal, choosing to stick to their vision.

Another early problem they faced was the fact that they were not based in Switzerland. This challenge led them to become self-sufficient and develop their own networks of local craftspeople, working around difficulties while maintaining a connection to the Swiss industry. “We are in Spain, not in Switzerland, or Germany or France – they have a closer relation with watchmaking. In Spain, this is something unusual,” Martínez says. “But we were born and raised here – I’m Catalan, my wife is Catalan, we are from Barcelona and our families are here. That’s the only reason. We feel comfortable here, but it is not always easy to make watches in Barcelona.” Yet in some ways, this would turn out beneficial to their work – the lack of widespread industrial watchmaking in Spain meant they were able to find suppliers and collaborators who did things the traditional way.

The Technical Details

The decision to use a vintage calibre in their watches was mainly practical, as they were easier to source, refurbish, and adapt, without the resources to research and develop a new calibre entirely from scratch. There was also the bonus of the authenticity such an approach gave the watch, and the satisfaction of expanding upon the AdC team’s desire to create something rooted in history.

The first movement they chose was the Omega 266, a historic calibre first created in the 1940s, originally derived from the Omega 30T2, and made for more than 25 years. They followed in the footsteps of other independent makers who used vintage movements as a base for their pieces, such as Kari Voutilainen, Christian Klings, and Jean-Baptiste Viot. Martínez says, “We started with the Omega 266 because in the past, this was a very strong calibre. It was also easy to find spare parts and easy to repair for any watchmaker, so that’s why we chose it.”

The refurbished Omega 266 in the AdC 1 Prototype.

There were also a few factors for why this calibre was an ideal choice, such as its precision, and the raw industrial finish that allowed for significant aesthetic modifications. Furthermore, at just 30mm in size, it would fit very well in a 36mm case, with the leeway allowing the team to add complications when needed. One modification that was made early on was the addition of a free-sprung balance without a regulator and distinctive click mechanisms.

As the Atelier de Chronométrie catalogue expanded, the majority of their watches continued to retain the Omega 266 as a base, but they also inducted other vintage calibres into their offering, adapting them to their needs as the team explored other complications. For example, the AdC 2 and 21 both make use of the Omega 283 as a base. Martínez says, “We chose this for the centre seconds – it’s the same movement as the 266 but with an extra bridge for the centre seconds.”

Some other calibres also found in the watches include the Venus 185 and 179 in the AdC 8 and AdC 17 respectively, which were chosen because of their rattrapante functions. “These are difficult to work with and to find,” Martínez notes. “It’s also expensive, because we used to buy the entire watch only for the movement … But we don’t have a lot of other options for rattrapante movements.”

Over the last ten years, the workshop has come into its own, with experience expanding their capabilities and refining their approach.

The split seconds was a particular pain point for Atelier de Chronométrie, because of how delicate the rattrapante movement is. Speaking very frankly, Martínez describes working with it as “a nightmare”. He adds, “Its delivery is always quite delayed. Right now, we are working on the third one – so far we have the No. 8, the 17, and the 99 – which will be the last one for now. It’s very difficult to adjust the rattrapante. You have to adjust the chronograph first, then the rattrapante, which is really difficult because sometimes you have a lot of weight in the hands and there are a lot of pieces in the rattrapante itself. The other problem is that we use vintage calibres – we only have one calibre and we don’t have spare parts. So if any problems occur, we have to make the parts one by one, which is very difficult. To make sure that everything works properly, both new and old parts, there are always surprises. Or problems.”

The Design Process

A sketch of a dial before it’s rendered in metal.

According to Martínez, the length of time for the design process depends entirely on whether the watch has a time-only design or is a complicated piece, and can take anywhere from one to three months. With their core philosophy and aesthetics in mind, there is a clear pre-existing framework for each watch that they work within, with the limitations sometimes bringing out something more creative than you might otherwise imagine.

“I always make a hand drawing of the watch for the customer,” Martínez says. “Then we make a 2-D technical drawing of the dial to adjust some issues that we might not have seen with the hand drawing. Then once the design is approved by the customer, we make a 3-D rendering of the watch – the dial and case with hands – so the customer can see what the watch will look like in the future.”

This level of collaboration is highly unusual for any watchmaker-client relationship, even for an independent manufacture. Starting out with hand drawing, for example, is a very traditional way of doing things, although modern touches are later added through computer modelling. The main idea is to cultivate a strong relationship between both maker and client, adding a more personal touch to the overall process.

However, Martínez also explains that they also have the responsibility of guiding the customer, and staying true to Atelier de Chronométrie’s core aesthetics. “We listen to the ideas that they [the customers] have in mind, we recommend the best choices they should make, and then we make our proposal. Occasionally when a customer has a ‘bad’ idea, we try to propose some arguments to demonstrate why that wouldn’t work, and that sometimes happens because they are not designers. We also try to interpret the things that they have in mind and give them a nice design and, in the end, they are happy.”

“This could be anything from a bad combination of colours, for instance, or elements. Something that is not well-balanced – or other strange ideas, like creating a case that would be impossible to make or not wearable on the wrist. Sometimes it’s simply things that are not in line with our style or philosophy. Because we are inspired by the past, we aim to make classic products. So, if one customer wants something strange, or if we don’t feel comfortable with those ideas, then we have to say no – there are other brands that make these types of products, but not us.

“We offer an experience to the collector, and they feel that they can be a part of the process, both good and bad parts. They understand the way we do things, and the challenges that we face.”

“We are in Spain, not in Switzerland, or Germany or France – they have a closer relation with watchmaking. In Spain, this is something unusual. But we were born and raised here – I’m Catalan, my wife is Catalan, we are from Barcelona and our families are here.”

The fact that the design of some of these watches relies on such close communication and a shaping of ideas with collectors has led to some intriguing projects, such as the four watches commissioned by Mark Rawlins for himself and his three brothers, the AdC 11, 12, 14, and 15. The watches were made to commemorate the close-knit ties between the brothers, with the added bonus of the linguistic connection. This is because growing up, the Rawlins family was based in Argentina and moved around Latin America, so communications with the Atelier de Chronométrie team also took place in Spanish.

“The idea was that we would make four watches, and each of us would take a different dial colour,” Rawlins says. “I gave the team a short menu of aspects of the watch dial that I love, like Arabic Breguet-style numerals. I think I wanted the hands slightly thinner than what had been typically used in previous watches. Then Santi took that list of things and he came up with the first sketch made by hand. It was very close to what we ended up with. We went through about three or four iterations of the design, because I was pretty specific as to the components I wanted, but the whole back and forth was very easy.

“Something that’s not always shown in pictures is the plaque that we put in the back of the watch, which is small and gold, with the date of our parents’ wedding anniversary, and then right below that it has either my initials or my brothers’ initials, just to make it slightly more customised to each of us.” Another nod to the collector community, which tied in nicely with the sentiment of the watches, was the personalised double signature placed above the seconds sub-dial. Rawlins says, “We were just batting ideas back and forth and I must have said something like, ‘Could we do Rawlins, or something simple in the dial signature area?’ I think that’s when Santi said, ‘Hey, how about we do kind of the equivalent of a double signature?’ I loved the concept and plus it kept the Atelier de Chronométrie – Barcelona clean so that it wouldn’t be different from all the other watches they make”.

The AdC Village

One thing is clear – while Atelier de Chronométrie is an independent manufacture, they straddle the line of being “independent” and a “manufacture”. Without a single watchmaker’s name that represents the entirety of the brand, there is instead the sense of a close-knit community, with the main Atelier de Chronométrie team facilitating and directing the overall creative flow of everyone’s energy. Furthermore, the emphasis on traditional skills removes any aspect of this being simply a manufacture, making them occupy a rather unusual artisanal niche.

Gimeno expands on the concept. “We make everything,” she says. “Obviously, we don’t make the jewels, the hairsprings, but in all other aspects we multitask. There are a lot of things involved, from designing, producing, communication, etc. A lot of people participate in the process. The core team is small, and we are hoping to expand and find new watchmakers, but there are other very close collaborators that work with us more or less everyday, so in reality it’s more than just three people.”

Some of the people in their long list of collaborators over the years include Gilwatch SA in Switzerland who they worked with early on in the manufacture’s conception for dials. According to the team, this is mainly because Barcelona does not have dial makers that meet the manufacture’s high standards, and their dials continue to be made in Switzerland today. However, Atelier de Chronométrie makes nearly all of the other parts of the watch in their workshop in Barcelona, such as hands, crowns, cases, movements, and buckles.

When it comes to the enamelling found on dials such as the AdC 4 and AdC 9, Atelier de Chronométrie work closely with the Catalan artist Josep Ronsano, who had in the past created enamel dials for Patek Philippe, as well as the sisters Margarida and Teresa March who have dedicated themselves to the craft for more than 50 years.

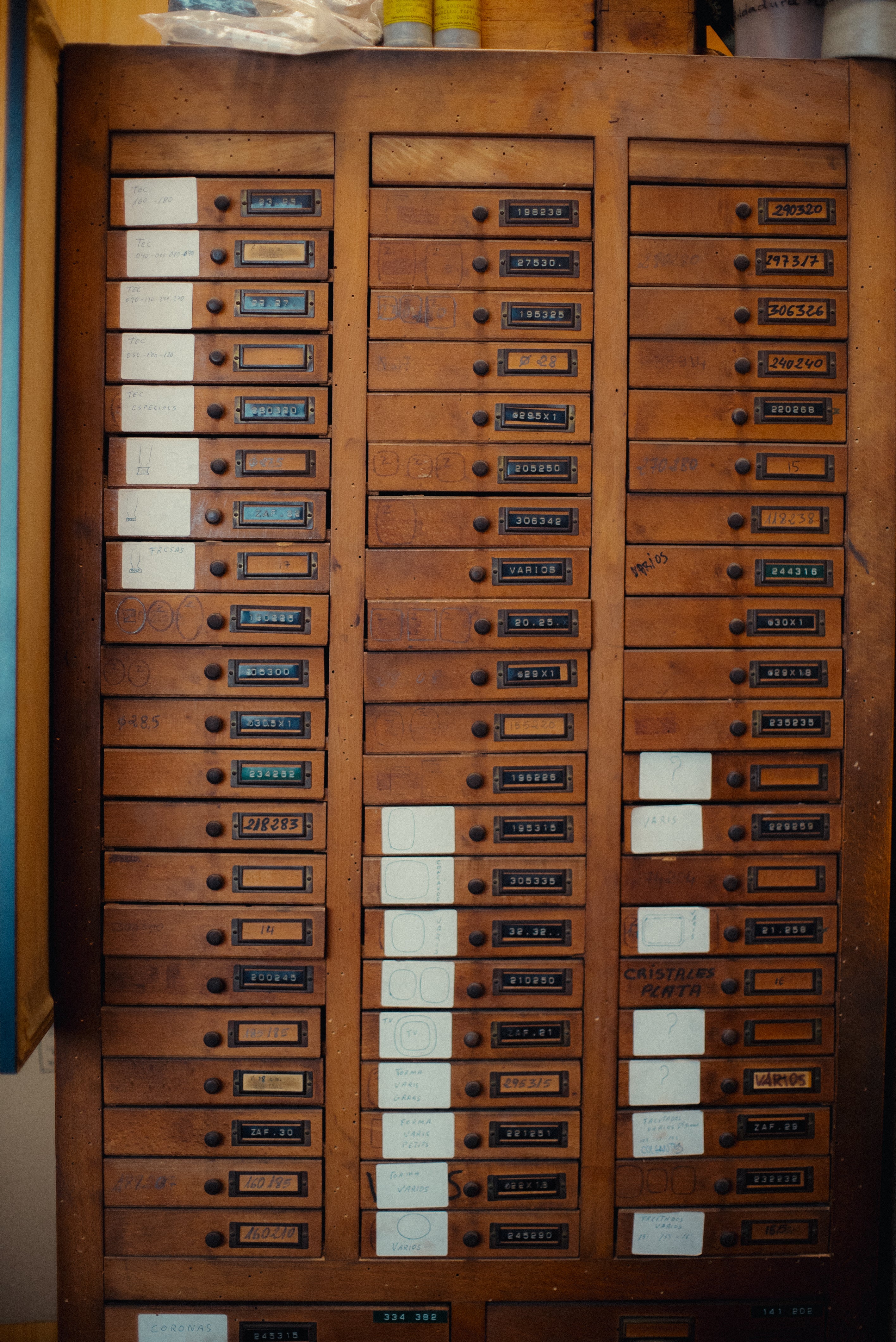

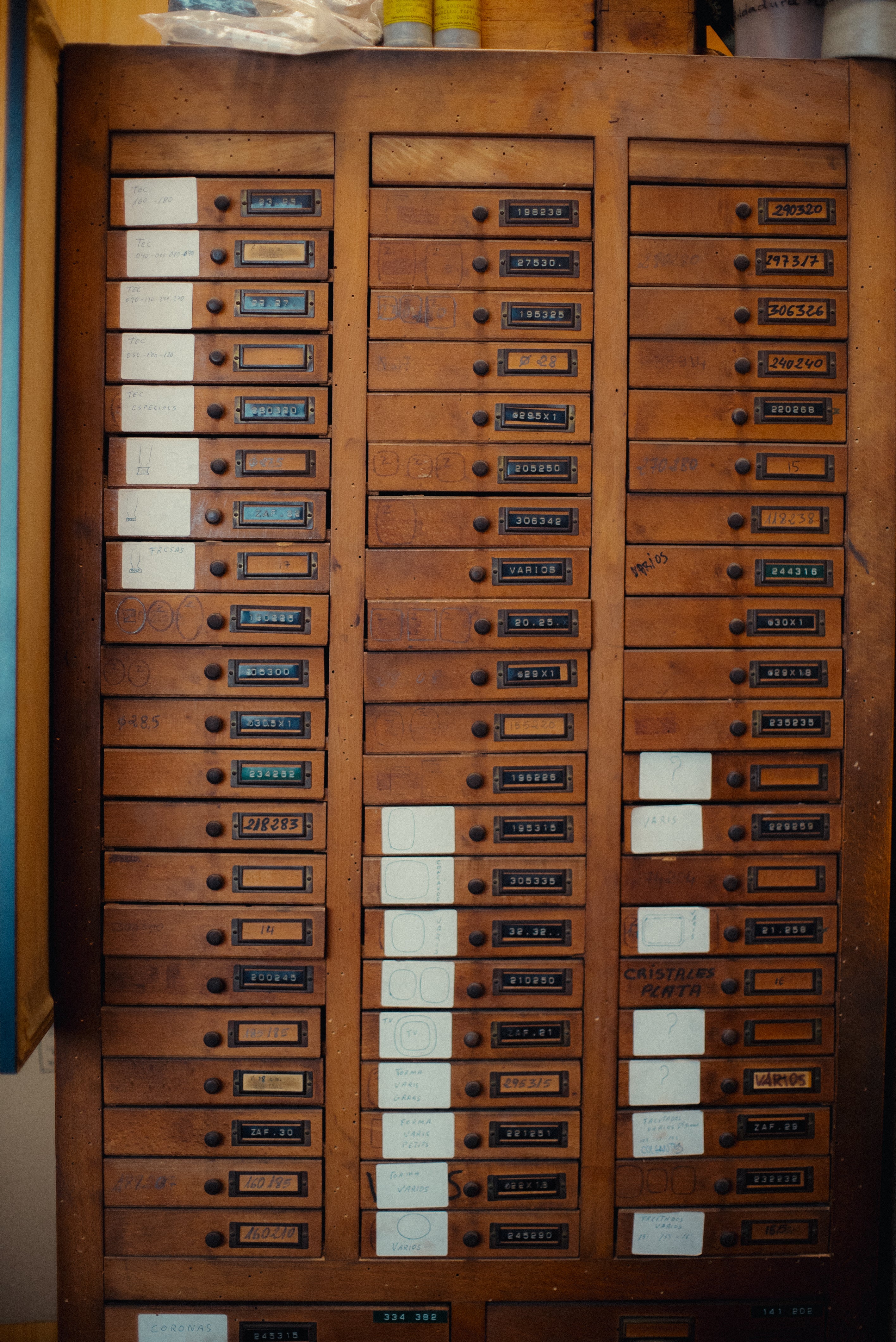

Details from their fascinating space, including a framed family tree of the last four González generations.

Two of their other standout collaborators include their casemakers, Victor and Helio González, who are second- and third-generation artisans that make all of Atelier de Chronométrie’s cases, bracelets, and buckles entirely by hand.

According to Gimeno, this process can take quite some time because of the artisanal process. “First, the bracelet beads are cast, and they are made slightly bigger than needed. After that, each link is filed down one by one, all of them by hand, to remove the extra material and the casting marks. We also create all the pins and screws [to remove links] completely by hand.

“Before bolting the entire bracelet, we pre-polish it by hand. Afterwards, we bolt the entire bracelet in rows and also solder in some special points to allow movement of the bracelet on the wrist. Once the bracelet is finished, we make the final polishing with some decoration, such as sandblasting on the clasp and hallmarking.”

The entire process takes from three weeks to a month – a lengthy but rewarding endeavour that produces very traditional-looking bracelets to complement the vintage-styled or true vintage pieces.

“A lot of people participate in the process. The core team is small, and we are hoping to expand and find new watchmakers, but there are other very close collaborators that work with us more or less everyday, so in reality it’s more than just three people.”

The Evolution of AdC

To date, AdC have officially produced 20 different models, all in either limited numbers or as entirely unique pieces. There is no strict numbering system for the watches, although several of the projects are placeholders that are still being worked on.

At large, each of the watches adopts several features that are shared with watches from the 1930s and 40s. These include but are not limited to: blued steel leaf hands, sector dials, or two-tone colouring on their dials. In general they possess a smaller case size with slimmer lugs. Here we provide a breakdown of some of their more notable models across their career so far.

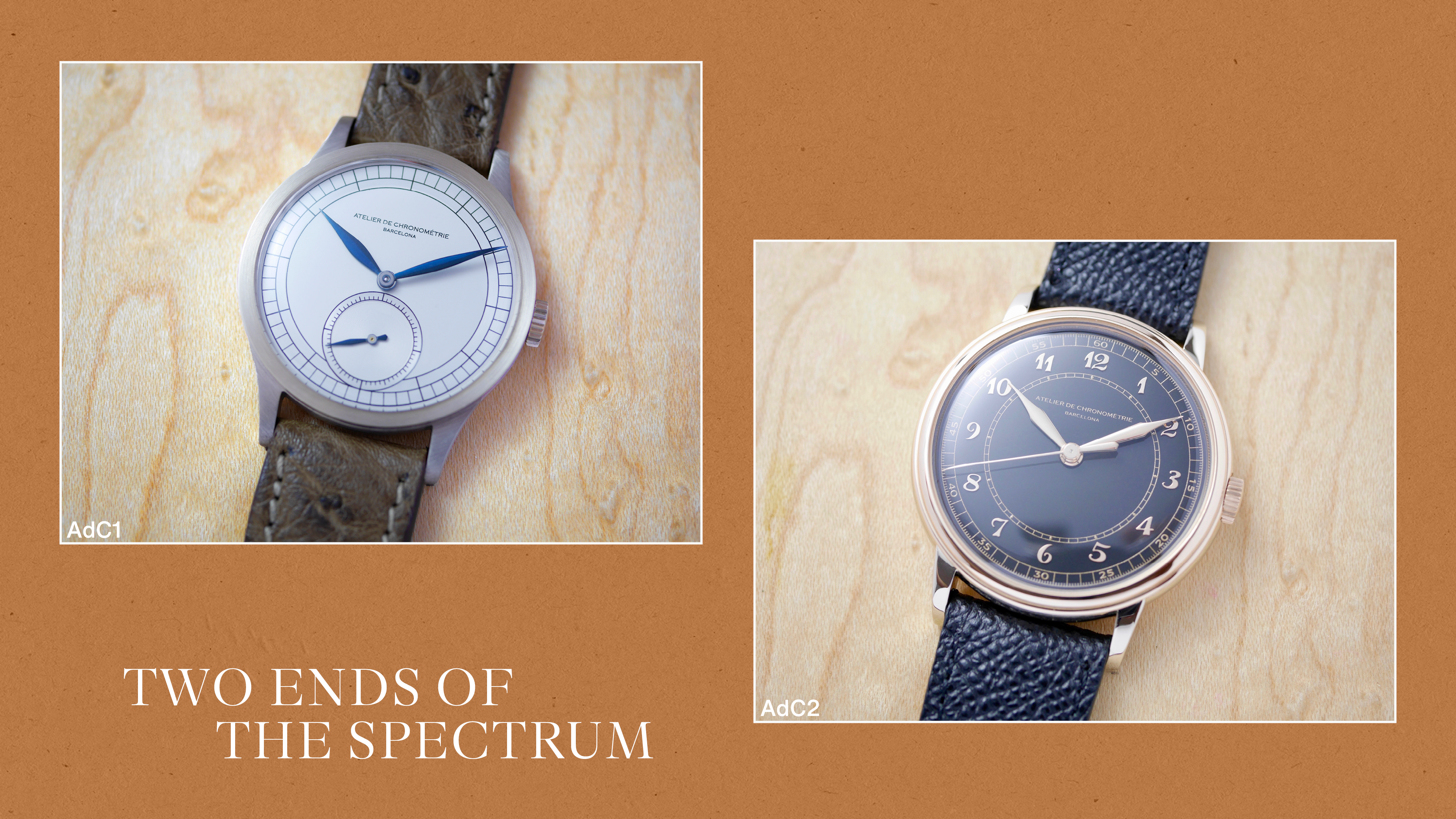

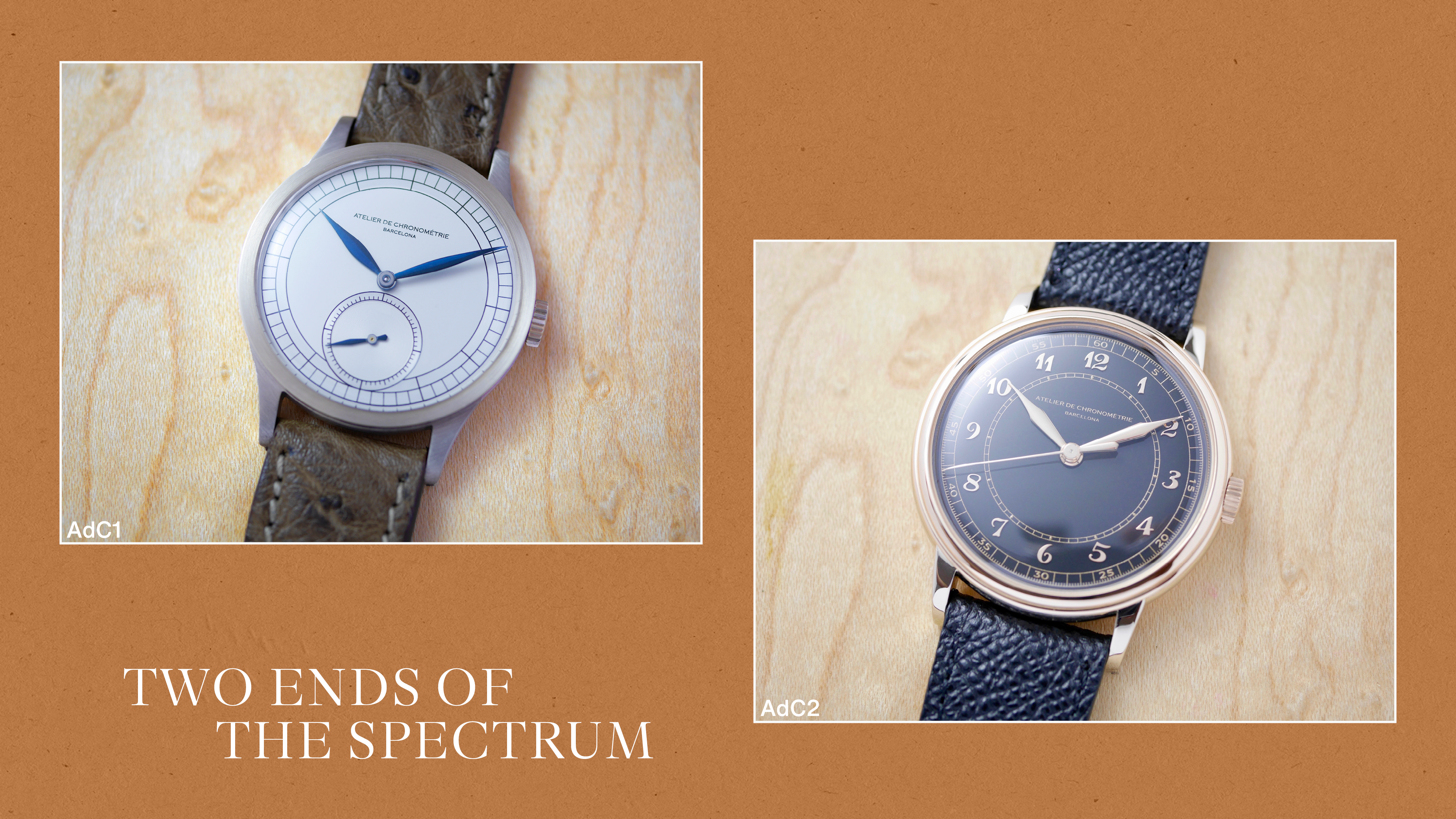

The first two watches to leave their workshop were an initial exploration of their aesthetic and featured an entirely remade Omega 266 and 283 respectively.

Both watches represented opposite ends of the spectrum – the AdC 1 keeping it extremely minimalist with a sector dial and sub-seconds, completely devoid of any indexes. Meanwhile, the AdC 2 evoked contrast with a black dial and gold markers, the Arabic Breguet numerals and seconds counter on the outer section of the dial. The AdC 2 was initially an experiment to try to create a bigger case (40mm) with a slightly different shape, but ultimately it was abandoned as the team felt it was incongruous with the style they were trying to achieve.

In both refurbished movements, certain aspects such as the wheels, anchor, balance wheel, main plate and winding mechanism were retained, while new bridges, clicks, caps, crown, posts, and some of the screws were made by hand. A titanium balance wheel was added, with aesthetic improvements such as polishing and bevelling added to the escape and ratchet wheels.

From the very beginning, the watches were distinguished by a high level of finishing on the movement, and in the case of the AdC 1, there was the added bonus of it being an Observatoire Chronometre, officially certified by the Besançon Observatory in France.

Expanding their catalogue and further delving into the possibilities of the vintage period they worked with, the AdC 4 was the first time that cloisonné enamel was used on an Atelier de Chronométrie watch. Crafted by Ronsano, this represented Earth and the moon as seen from outer space. With the AdC 4, around 42 parts had to be hand made, and the four bridges were constructed from German silver.

The AdC 9 continued their experiments with enamel, this time done by the March sisters. The dial depicted the Milky Way galaxy seen from a distance, with over nine layers and a process that included baking the dial seven times at temperatures ranging from 800 – 1000ºC. The movement itself integrated a new ratchet click compared to previous iterations.

Both the AdC 4 and 9 integrated a rarely seen complication that causes the dial to rotate, allowing the view of Earth and the Milky Way to change over the course of five and 23 hours respectively. Both watches demonstrate Atelier de Chronométrie’s potential, going beyond vintage elements to incorporate more whimsical and poetic sensibilities.

With the AdC 5, Atelier de Chronométrie truly began to hit their stride, achieving mainstream success with the combination of a two-tone dial, blued steel hands, and Breguet numerals.

Overall, the design was kept simple but slightly cleaner compared with the previous examples, and proved irresistible to collectors. The watch just so happened to be an excellent confluence of elements, and brought their emphasis on vintage styling to the forefront.

This run of watches marked a growing collaboration with Shellman Japan, an early affirmation of Atelier de Chronométrie’s concept that continued into the later numbers as their partnership developed.

The AdC 6 boldly took an even more vintage-inspired size, with a 35mm case size aimed at a Japanese audience, while its design closely followed the AdC 1. The watch also marked the first use of an in-house developed machine that allowed them to create their own form of Côtes de Genève.

With the AdC 7, a follow-up collaboration, we see that the style was a variant of the AdC 2, keeping the Breguet numerals and adding sub-seconds.

Later on in 2021, the AdC 18 would introduce a new design for Shellman, a galvanic black gilt dial – a design mirrored and expanded on from the AdC 88 released a few years earlier. The AdC 88 also featured a redesign of the case integrated in all subsequent watches, two dial variants, as well as a escapement wheel bridge made from carbon steel.

The AdC 31 was created in honour of Shellman’s 50th anniversary and featured a grand feu enamel dial with baton indexes. A later piece, this also was powered by the newer M284, rather than a reworked vintage calibre. Overall, it continued a fruitful relationship that served to underscore Atelier de Chronométrie’s close alignment with the vintage space and their inventive methods of incorporating vintage features with a modern twist.

As described earlier in the article, this run of four watches was made for the Rawlins brothers, and does feature a few things not yet seen on other AdC pieces, such as the double-signature on the dial and the variation in dial colours. In all other respects, however, they are clearly part of the AdC oeuvre, with a tasteful vintage-inspired design.

What this small collection highlights, however, is not just their focus on design, but how the process of creating a watch can be so personal, as well as how the smallest touches can hold great significance. Interestingly, the choice to exclude the number 13 from this run may have been conscious, given that it’s largely an unlucky number in Western culture. It remains to be seen if an AdC 13 will materialise later down the line, but that’s an entirely separate question.

Montse Gimeno

In 2020, having firmly established themselves with their time-only work, Atelier de Chronométrie ventured out of their comfort zone with the AdC 8, a split-seconds chronograph. The watch featured an entirely new case with teardrop lugs, inspired by vintage chronographs. Meanwhile, the dial had a pulsometer scale rendered in galvanic gilt on black, overall adhering closely to vintage examples, and especially reminiscent of Patek Philippe chronographs. The watch was a finalist in the GPHG awards for that year, in the chronograph category.

The difficulty of working with the Venus 185 ebauche has been documented above, but clearly the team had quickly forgotten their previous struggles, as they embarked upon the AdC 17 three years later in 2023. Based on the Venus 179, this was another unique piece with an unusual aviation KNOTS tachymeter scale requested by the client, in a vibrant salmon. The rattrapante only featured two counters, as opposed to the three with the AdC 8.

There are several other projects listed under the complications section on their site, meaning there are quite a few more upcoming pieces we can look forward to, including more triumphs over chronometry and all associated chronographs.

These watches marked a new era for Atelier de Chronométrie, as they were powered by an entirely new calibre designed from scratch with Luca Soprana. The design of the AdC 22 was kept very simple, allowing the calibre to shine through. At this point, it was a prototype with the team continuing to improve on the calibre. Meanwhile, the AdC 25 was the third example to be fitted with this movement, and was a reworked design of the AdC 88, with a vibrant blue galvanic gilt dial that hadn’t previously been used on other examples.

The Future and a New Calibre

With the growth of Atelier de Chronométrie, new directions had to be taken, and it seemed like a good time to introduce an in-house calibre. Sticking to the Omega 266 was not a sustainable solution and was quickly becoming a limitation. Gimeno explains their thought process. “One of the reasons was because we were not very happy with our previous calibre,” she says. “We wanted to improve and make a technical step forward. Also, right now it’s quite difficult to find a good Omega 266 base to continue to make watches under our previous system. But anyway, we always had the idea to make our own in-house calibre. We knew that at the beginning it was impossible, and it was easier and more practical to work with the Omega 266, but we knew that at some point we needed to make a step forward and create our own.”

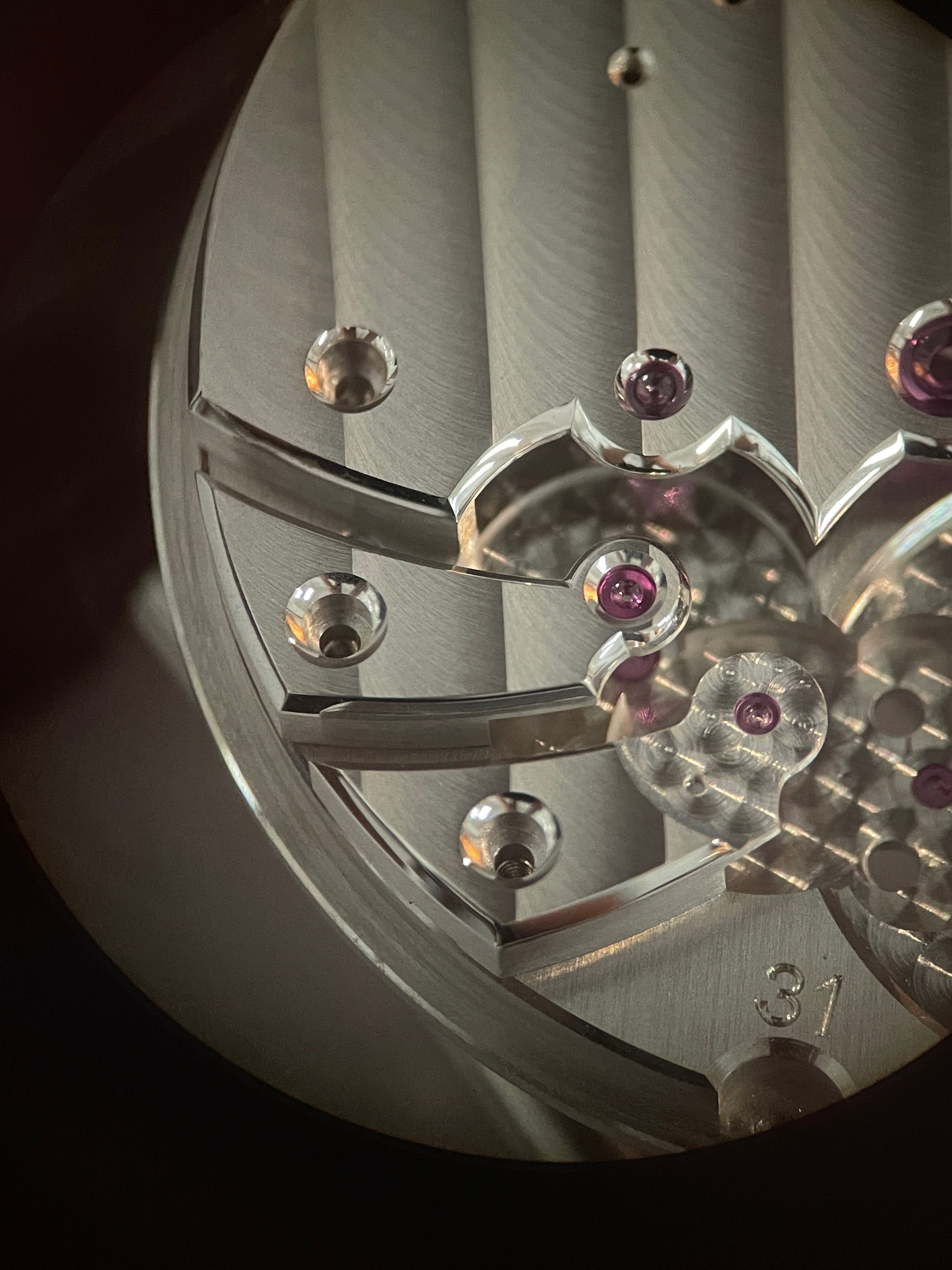

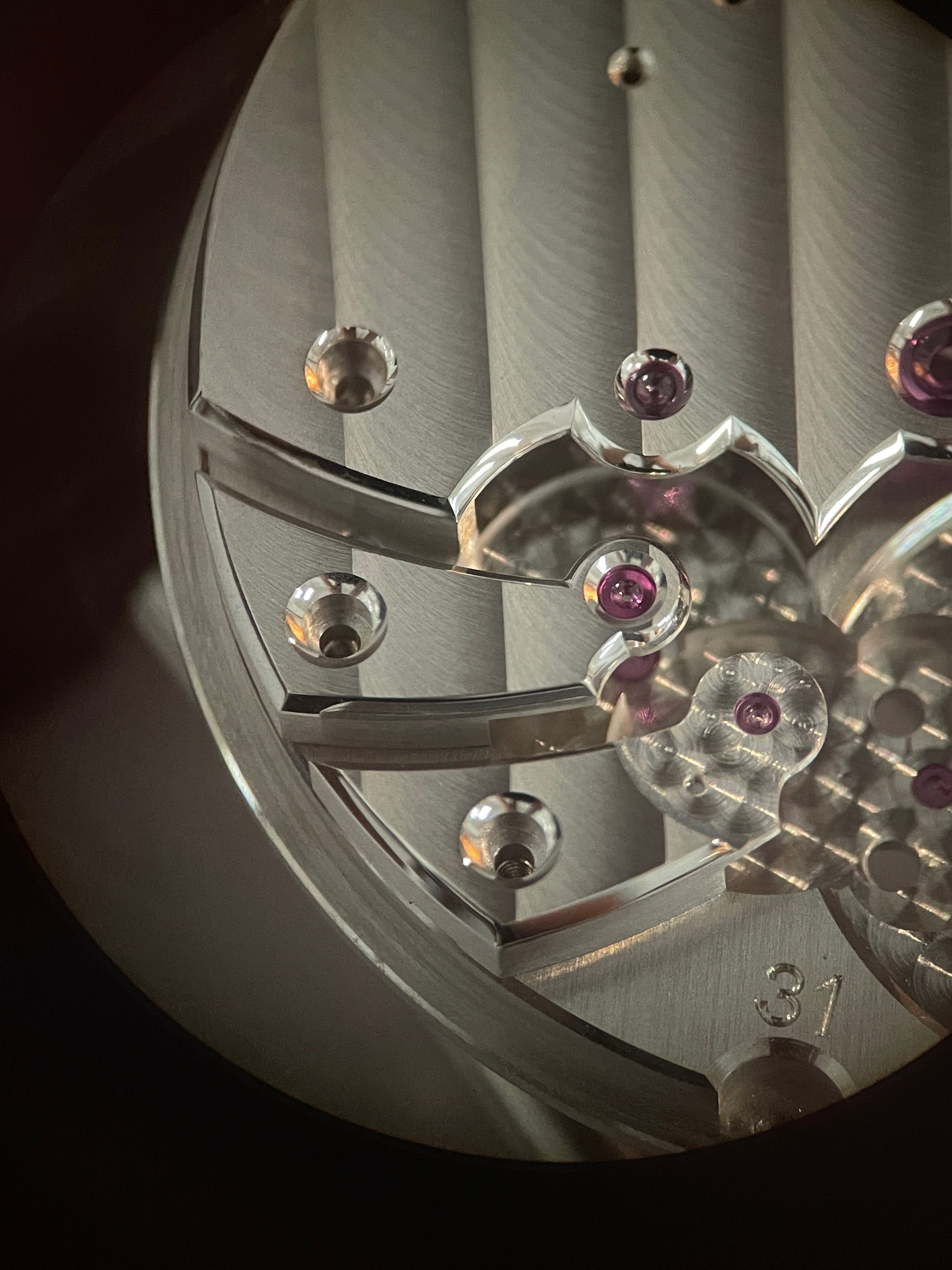

The mainplate of their new in-house movement, the M284.

The first question was: where should they start? Naturally, the answer would be found in vintage calibres that allowed for more experimentation. They eventually chose to base their new calibre on the Patek Philippe calibre 13-130, a significant piece in the history of chronographs.

“It took more than a year to develop the new calibre,” Martínez says. “We worked with Luca Soprana for this, and he [has been] a friend of ours for many years. We share the same passion for vintage movements, pocketwatches, and they helped us develop the calibre both technically and aesthetically. The idea was to create a calibre inspired by old observatoire chronometer movements, Geneva style. Very classic, something like the Patek 13. The idea was to make something that brings you back to the past. So that when someone sees our movement, they have the sensation of seeing a calibre from the 40s.”

Luca Soprana, an independent watchmaker based near Neuchâtel, is best known for his work on the Derek Pratt x Luca Soprana Remontoir d’Egalité as well as his “Old School” collaboration with Massena LAB, the latter of which has an aesthetic that makes it no surprise he would decide to work with Atelier de Chronométrie, given their shared sensibilities.

He mentions that they did not set out to create a new calibre, and that he was initially advising Atelier de Chronométrie on some technical issues they were having with restoring an old calibre. However, their partnership soon evolved into the creation of an entirely new calibre.

“I was mostly looking at pocket watches for inspiration,” Soprana says. “The big bridge found here [on the 284] is perhaps more common on German bridges, and I would say this is quite a special feature, because the style is also in the style of the 40s. We wanted to keep a very classic dimension of the movements, at 30mm. But the idea was really to respect the Geneva style in the sense that for the watch, if it was done in Geneva, it would be able to achieve the Geneva seal.”

According to Soprana, they also tried to keep modern elements to a minimum while creating the watch. “So it was easier for things to be done in a manual way, and totally by hand,” he says. “That’s why we also tried to make something like the teeth quite big, so that at the end of the day, all the components can be redone by a watchmaker in 10, 20 years, if the knowledge is still there.”

Since creating their own finishing machine, which was first put into use on the AdC 6, most of the movement finishing is done at the Atelier de Chronométrie workshop. The image on the right demonstrates the finishing on the AdC 31, with sharp bevelling, Geneva stripes, and perlage visible throughout.

A final consideration was also the fact that the calibre could be modified for any future complications, giving the team more room for creative freedom. “That’s why we chose to have a powerful mainspring, so the piece can have an evolution,” says Soprana. “It’s really ideal to have a basic calibre that allows more future development. It can easily be turned into a chronograph or any other complication.”

In the finishing particularly, Soprana’s level of attention to detail shines through, as even the size of the big bridges was calculated according to the number of Geneva stripes that the Atelier de Chronométrie team wanted to include on it, as all the finishing on the calibre is done entirely in their workshop. “We decided to put them at an angle and position where you can get the maximum visibility and you can get it into all the bridges,” he says. “I think that’s why they [the Atelier de Chronométrie team] got in touch with me, because they know that I’m very picky when I do this kind of work. I know the importance of that, and I think that is the big difference when you have someone designing the movement that is a watchmaker, and that has experience in restoration and development for other brands.”

There is more on the horizon for the new calibre, as Martínez and Gimeno shared that they are in the middle of continuing to improve the movement, continuing to tweak the escapement and the design in response to that, so we can expect to see a continued evolution of the M284 in the coming years.

On the Future

More than a decade later, Atelier de Chronométrie has largely stayed the same size as it is now, although their name has grown in stature and respect amongst collectors. Although they are determined to expand to meet demand, they are just as determined to retain their independence.

When asked about why they would choose to walk down this path, Gimeno says, “We don’t have any investors, and for us, independence means freedom – to make mistakes, to learn on your own, but without more pressure than the pressure you give yourself, and your own responsibility”.

Martínez concurs. “We feel that outside pressure will affect our creativity and philosophy,” he says. “Being independent gives us the freedom to create the designs we want and not be conditioned by the market. If we have to say no to someone, we say no to someone. We want to focus on the product, and the product is the result of our hard work.”

With the development of their new calibre and continued commitment to artisanal methods, it will be interesting to see how they continue to expand on their aesthetics.

There is much in store for Atelier de Chronométrie, and it’s clear that we can expect other intriguing pieces to leave their workshop in the near future. Their list of current projects seemed to go on and on, with some details about certain watches withheld (naturally, to heighten the surprise), but leaving a still-impressive amount on their plate.

“Right now, we are working on the creation of a new chronograph movement based on the Valjoux 23, and we are making five of these watches,” Martínez says. “We also have a very interesting project, which is a World Time with a cloisonne enamel dial made by Josep Ronsano. It will be a very classic World Time with a black dial. We have to create the World Time module to add to our in-house calibre. Then we are working on a super interesting project which is the creation of a tourbillon based on an Observatoire movement made by Longines. We found a box of seven movements, and it should be a fantastic project.”

Gimeno adds, “There is much more to come – things that are very original, very different when it comes to complications, shapes. We will also be making a series of watches with some retailers in Hong Kong and Japan, so we are very busy.”

One thing is for certain: the future for them remains vintage, a refrain that is consistent with their past and continued in their dedication to handcrafted pieces made in a community of skilled craftsmen and artisans, designers, and watchmakers.

Our thanks to the Atelier de Chronométrie team for inviting us into their space and sharing their work and experience.

Photography by Neal Fagan.