Looking Back to Look Forward at the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet

Kwan Ann Tan

What have we lost in watchmaking today? Amid the annual flurry of novelties, endless variations of the same watch in slightly different hues, and watches drawing upon ideas of heritage and nostalgia, is the world condemned to either pastiche or excess? If we take a step back from it all to observe this demand for the new, the fresh, and the novel, what might we really uncover about the watch industry? How do we discover what has been lost – and by what means can we discern the past’s influence on the future?

More than ever, the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet keeps its gaze firmly fixed on the future. The institution is a masterclass in design and curatorial practice, but represents something more. It is an impressive shaping of Audemars Piguet’s narrative, cementing its historical importance through the creation of this space. It also shapes public understanding of its surrounding location, the Valleé de Joux, which has long been hailed as the cradle of modern watchmaking. But can the past be an indicator of the future that Audemars Piguet intends to carve for itself?

We dive into the practicalities of what makes the museum tick, exploring the experience of digging through the archives, as well as restoring and interpreting the histories of the watches they curate. We also contemplate the shifting perceptions and cultures that influence the museum, before examining what the past has to offer – and how the way it is presented can reveal about today’s watchmaking landscape.

The Heart of the Valley

The drive to Le Brassus from Geneva is only an hour, but it seems much longer due to the winding paths taken to get there. The city melts away into an endless landscape of vibrant greenery, roads snaking around the natural rise and swell of the Jura mountains. On a rainy day, and especially early in the morning, you might be forgiven for mistaking the small, sparsely populated village that rises out of the mist to be some kind of fantastical location.

Past the tidy, whitewashed buildings, and right next to the Audemars Piguet manufacture, is the elusive Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet and the accompanying Hôtel Des Horlogers. Designed by Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) – a multinational architectural firm that won the competition Audemars Piguet hosted in 2014 to search for a structure that would blend with, rather than overshadow, the original workshops – the museum building is like a spiral, reminiscent of a tightly wound hairspring in a balance wheel. The structure appears to rise from the ground, a neatly kept strip of grass completing this subtle camouflage. Despite its striking yet slightly out-of-place modernity, a quick glance upwards through the skylight in the museum’s foyer allows you to see the original Audemars Piguet building looming above, an inescapable connection and reminder of their history.

The original Audemars Piguet building, slightly modernized but with its historical condition largely preserved.

It is the Musée Atelier building that houses the cultural heart of Audemars Piguet, containing its historical archives and acting as a diplomatic hub for visitors from all around the world, while projecting and shaping the brand’s image through the vivid object-histories of the watches in the museum’s displays.

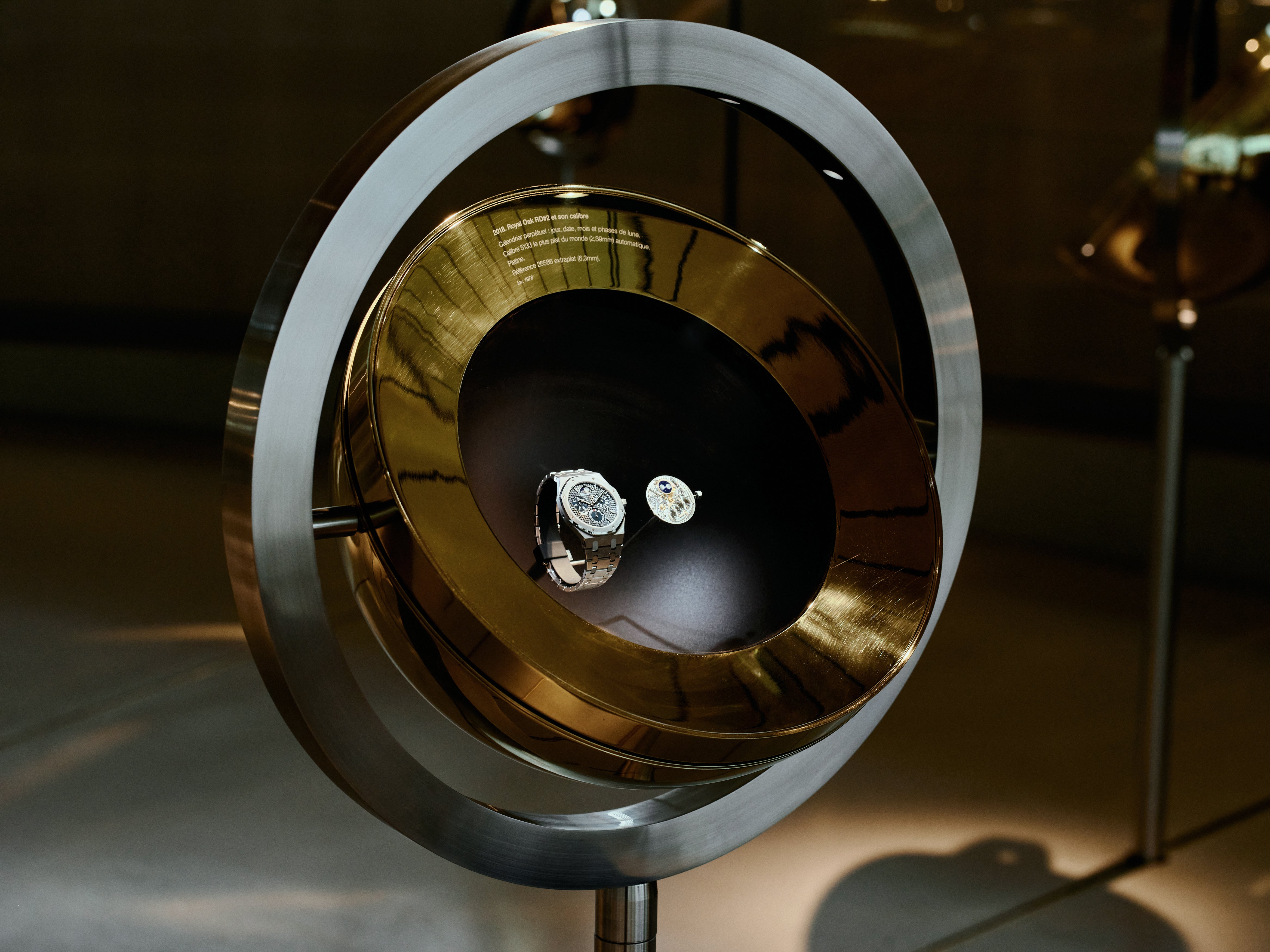

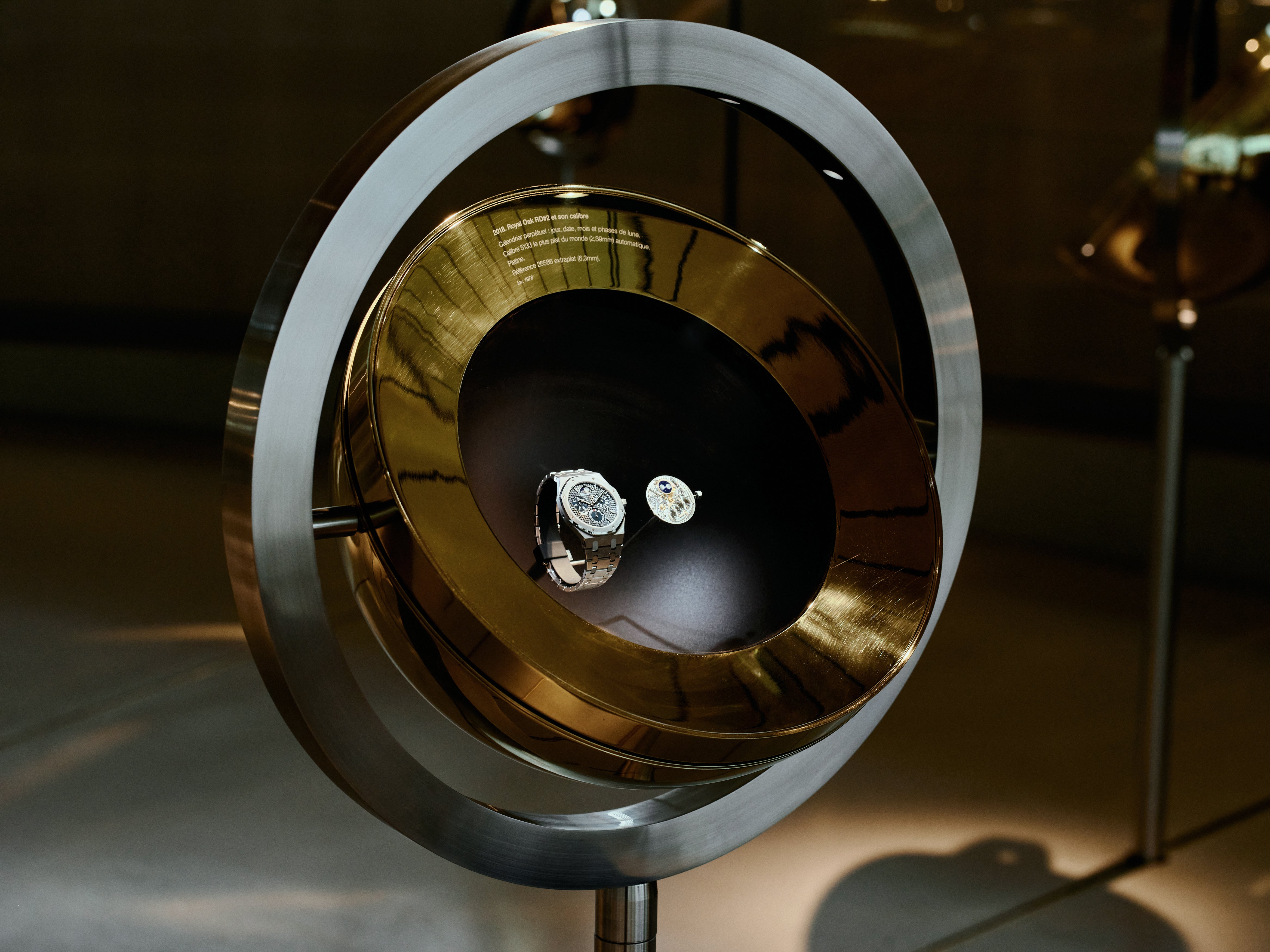

The space itself has been calibrated to a knife point of luxury, carefully giving off the impression of warmth and effortlessness, while being very thoughtfully arranged to foreground the visitor’s experience. Glass cases are interspersed with kinetic sculptures and familiar complications blown up to a larger scale to reveal how they work. The Royal Oak display takes up a significant and impressive section, complete with a dramatic reveal of black screens playing a video and lifting upwards to reveal row after row of Royal Oaks.

The museum can only be accessed by invitation only, so visitors are few and far between; in the intervening periods the space is transformed into a quiet area of contemplation, almost like a church of Audemars Piguet. However, the museum is also very much a working space. As you move through the spiral, the outermost section features watchmakers busily working at their desks – the museum is home to the those in charge of creating the Grandes Complication and Métiers d’Art pieces, with the restoration team working at the very top of the building.

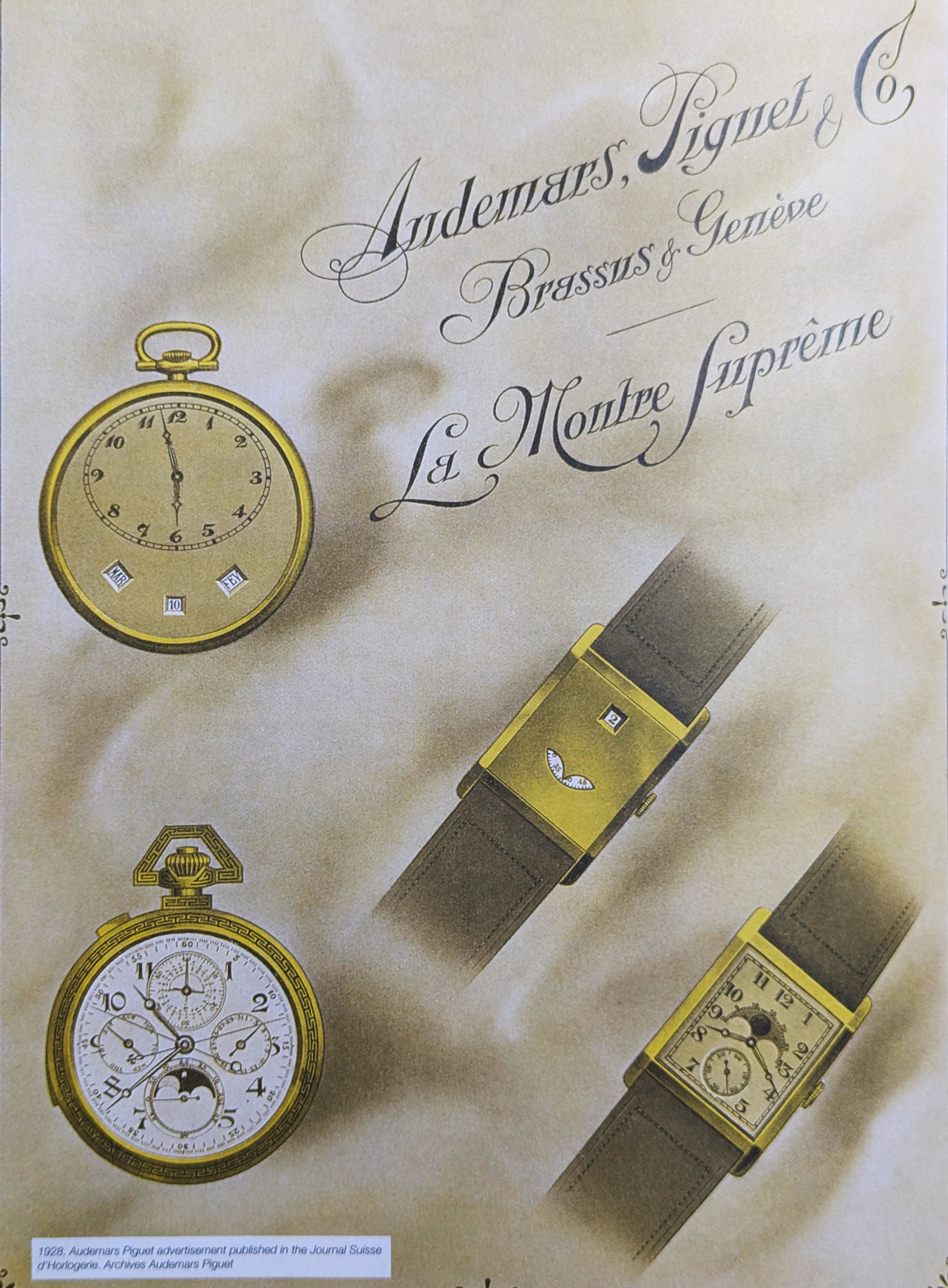

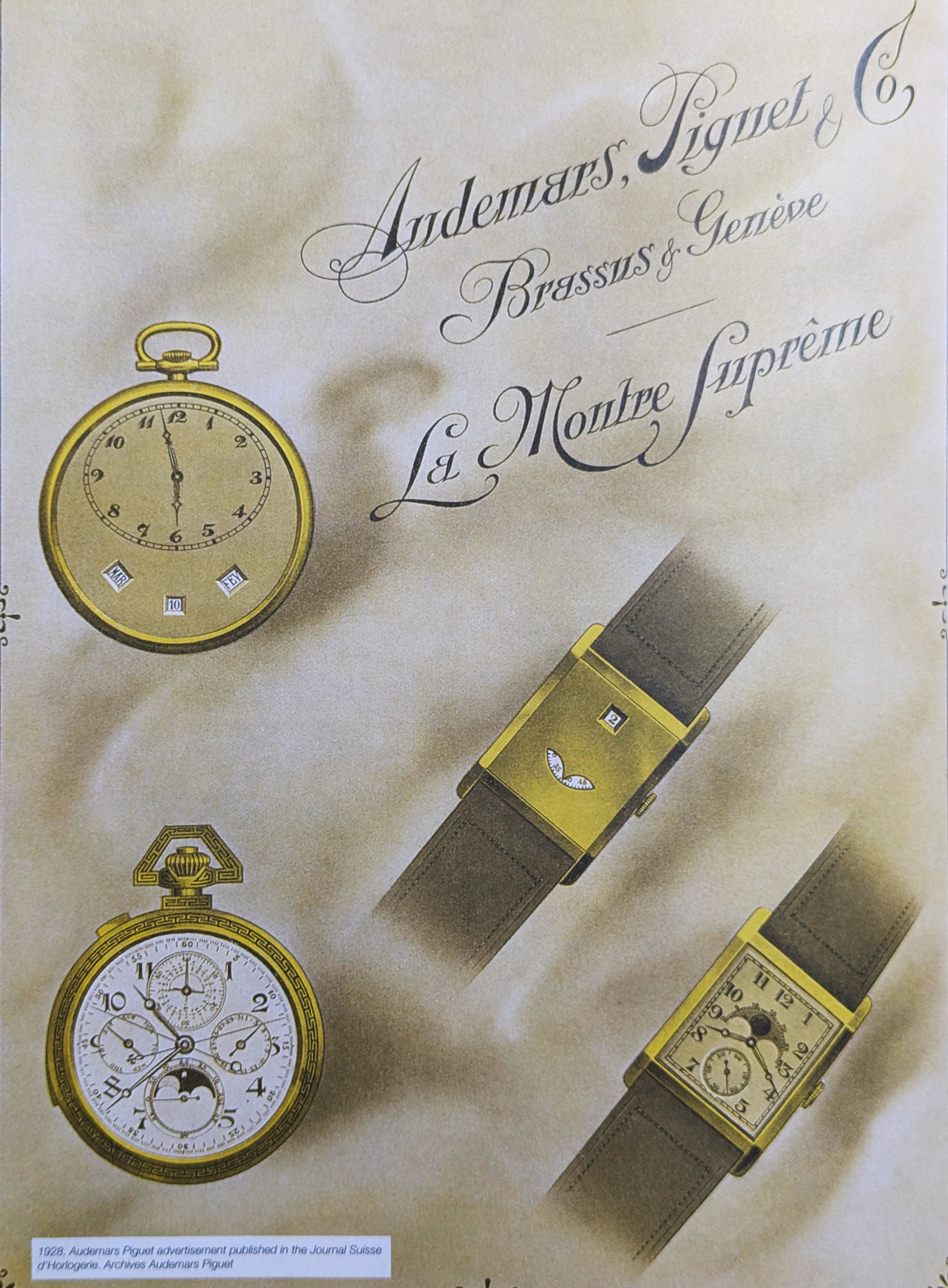

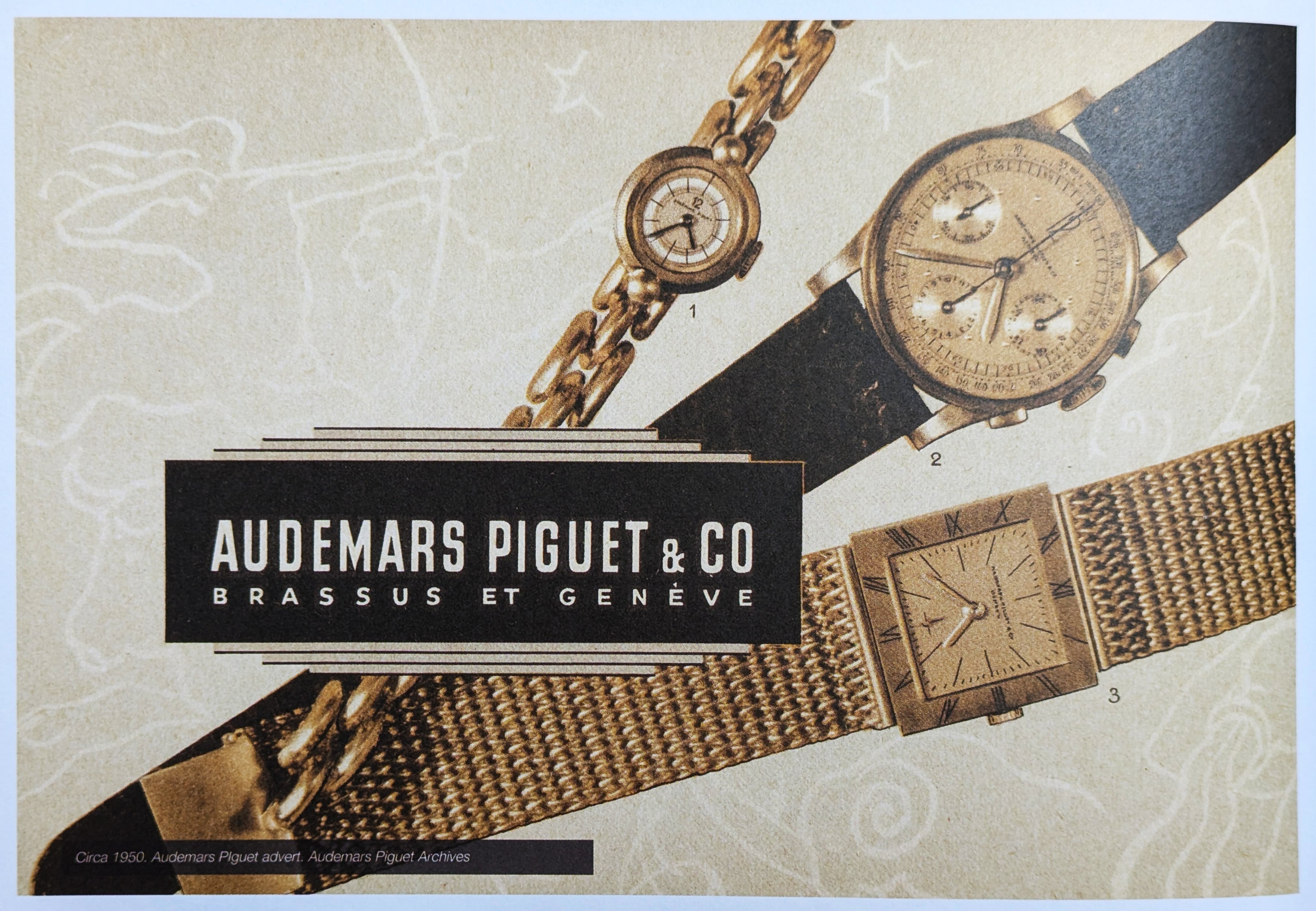

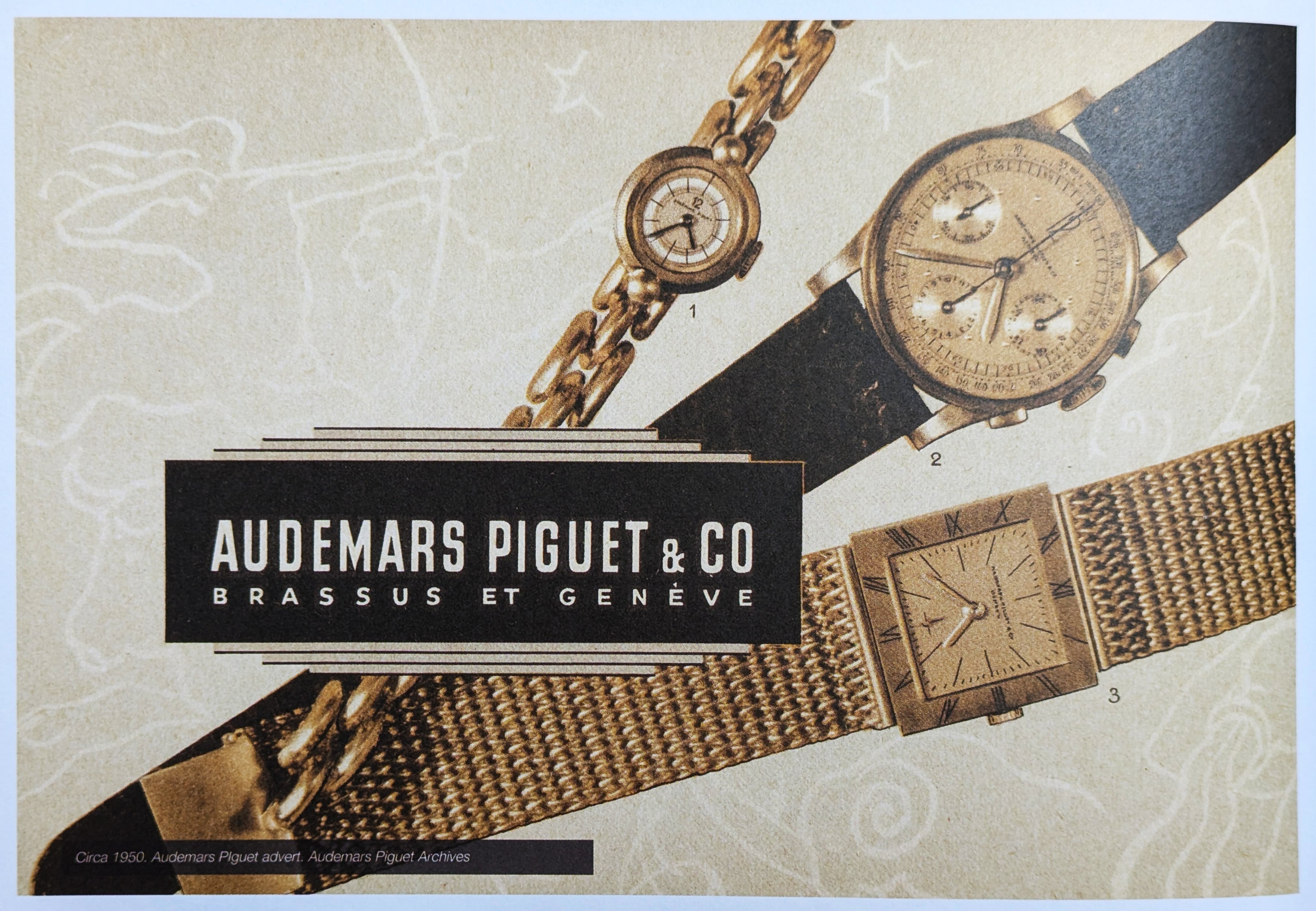

Taken from the Audemars Piguet 20th Century Complicated Wristwatches, published by Audemars Piguet.

In the core Heritage and Museum department, the team consists of historians, watchmakers, archivists, and specialists – a fairly small group of 12 people. Their role is not just to manage and curate the museum, but to sift through the archives, bringing the heritage of the company out of obscurity and to a wider public. This goal has been spurred on in recent years by collectors’ intense interest in aspects of the brand’s past, closely scrutinising and studying the tiniest of details.

However, to appreciate the work that goes into creating the image of a brand, we need to dig deeper into the inner workings of the machine that keeps this running, and the thought process behind everything.

Stars of the Show

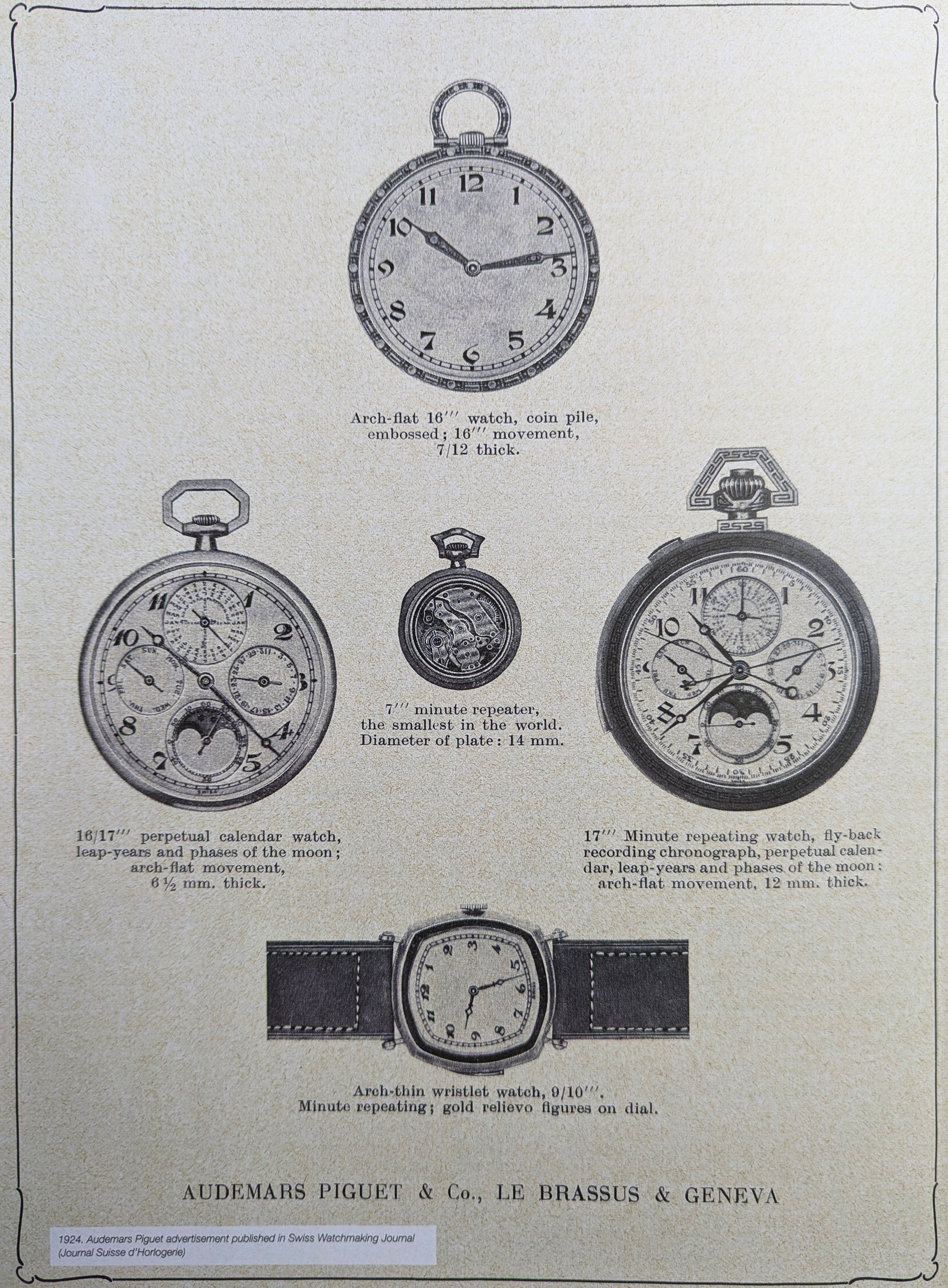

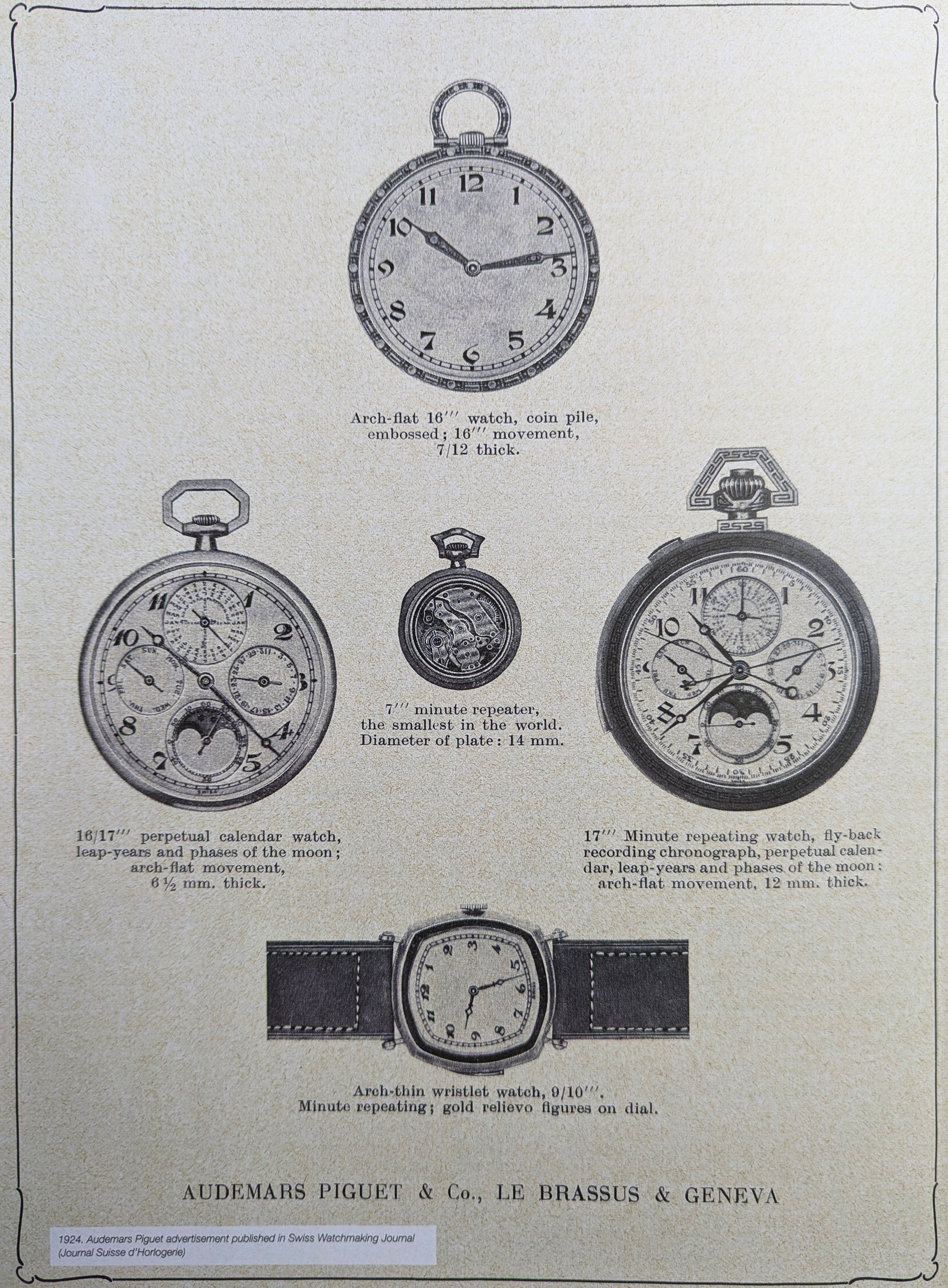

Moving through the space, there are some standout examples that demonstrate the museum’s long history, such as the complicated pocketwatch created by Jules Louis Audemars himself that served essentially as a “school watch”, representing the culmination of his apprenticeship. Tiny, jewel-set clocks in rings and necklaces inevitably draw the eye, as do highly complicated pocketwatches, which encompass chiming, astronomical, and timing functions.

For those who enjoy the classic style of perpetual calendars, an example created in 1957 – one of only nine – suggests an entirely different layout compared to the sub-dial heavy 1978 watches. This earlier era is also marked by pieces in various other forms and shapes from brands with a comparable history, such as jump hour examples, asymmetrical cases, and chronographs.

As we walk further into the heart of the spiral, travelling into the modern era, we see repetitions on a theme, as well as daring concepts brought to extremes in search of the possible limits of watchmaking. Some of these include the Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie, or the Millenary collection, which lean more towards being thought experiments made real in an attempt to redefine watchmaking.

It’s clear that a lot of work has been put into the arrangement and choice of watches, all in an attempt to capture centuries of history.

The Practicalities of the Archive

We meet Sébastian Vivas, the heritage and museum director at Audemars Piguet, over Zoom. He previously worked at the Musée International d’Horlogerie, as well as Jaeger-LeCoultre’s heritage department, before joining Audemars Piguet in 2012. The attic space of the original building has been transformed into offices and meeting rooms, with wooden beams running through the ceiling and framed by a nearly 400-year-old building – which makes it all the stranger to see Vivas’ face projected on a large, sleek screen.

When asked about the state of the archives when they first started to sift through and uncover the history of Audemars Piguet, Vivas explains that the building we were in was essentially where everything started.

“We have kept quite a few things in this building,” he says. “And today, the archives are underneath the museum in a very secure place where we have access to documents, information, and other things. Not everything, because we are still looking for certain bits, but things have been seriously professionalised during the last decade. We keep what we consider necessary for future generations and enrich the existing collection of historical pieces.

“We have a very rich and dense collection that covers all the specialities of Audemars Piguet’s history, but that also goes further into different areas before Audemars Piguet or different types of techniques like movements, decorations, etc. So, we take part in the creation of the museum, from temporary exhibitions to publications such as AP Chronicles.”

As with any large body of materials with shifting and inconsistent forms of organisation, the hardest part is devising a system of categorisation – of first discovering the limits of what exists – before beginning to decide what is important and worthy of displaying in the museum or sharing more widely.

When asked if there was a movement to digitise the archives, and possibly make more of them available online through AP Chronicles, Vivas says, “Before we digitise, we need to classify everything. It’s an ongoing process. For me, the digitisation of the archive is just one tool, maybe to preserve some of the original look and to get access without touching the original document. Some people believe that if you digitise everything, you keep everything, but this is wrong. Context is very important in understanding the circumstances in which these documents were created, and their contents. You don’t approach history through digitisation.”

Intriguing typography on an “extra flat” pocket watch dating from 1923.

Expanding upon the process of trying to search for information, however, Vivas admits that the work could sometimes be an uphill battle, simply because some things had been lost to time or were not possible to verify with certainty. “Each time we began our research, we discovered something unexpected. It’s super cool, but it’s also a bit frustrating. However, we now know that this is something that we don’t know, which is already a good start.”

This is true even when it comes to one of the most well-known and beloved watches of the modern era – the Royal Oak. Despite being just 50 years old, the stories and myths around this emblematic watch have become confused over the process of the watch’s growing popularity.

“When we started to prepare for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Royal Oak, we said OK, this is probably one of the most well-known watches in the world,” Vivas says. “There are hundreds of publications – books, articles, podcasts, whatever.

“But when we started to ask more questions, we couldn’t find the answers, or we found contradictory answers. So we had to go back to the original documents and really rewrite history. Sometimes someone on the team would say: ‘Look at this – I found this letter that says it did not happen the way we always thought it had happened.’ We did the same for the Offshore. We discovered, for example, that the name ‘Offshore’ was inspired by a German director who distributed the brand, who did not himself remember that he had suggested the name.”

The work is hardly finished – Vivas and his team are currently hard at work preparing for Audemars Piguet’s 150th anniversary, not only attempting to uncover more of the brand’s internal history, but also placing it within a wider landscape.

“We are discovering very interesting material that takes us not only back to 1875, but way before,” Vivas says. “We are recreating and rebuilding the link between the founders and the very first watchmakers in the Valleé de Joux in both the Piguet and Audemars families [and] between the other watchmaking families.”

Pocket watches through the ages – the overlap of styles seen across brands is largely thanks to an ecosystem of craft that exists in a different form today.

An interesting thing to note is this idea of a shared, interconnected history between the watchmakers of the region and around the Jura mountains. Keeping in mind that a more open and interconnected relationship existed in the industry back then, it comes as no surprise that the archives of Audemars Piguet hardly exist in a vacuum. There is a constant flow of communication with other brands in order to corroborate information or to find out how they might be connected, ultimately rediscovering the finer details of this historical industry and community.

Discovering Hidden Gems

The task of trying to piece together a fuller history is one that requires a lot of work. Even as the heritage team is constantly discovering historical pieces recorded within the archives, they also keep a close eye on upcoming auctions, and occasionally find the unexpected through collectors. Famously, auctions have played a significant role in these types of collections, such as in the origins of a contemporary institution, the Patek Philippe Museum. There, Philippe Stern was well-known for buying any notable pieces that appeared at auction, or from collectors, for the museum’s collection. However, what happens when you see a watch in the archives that you can’t seem to find anywhere?

Vivas explains that the auctions and the catalogues produced by auction houses are the tip of the iceberg when it comes to acquiring watches. Each auction season they have a meeting to decide which watches to acquire and how to allocate their budget accordingly. “We often buy watches at auction, such as the Geneva auctions,” he says. “Each time, it’s a discussion – why is this one meaningful? What story does it tell? To whom? When, and how? It’s the same for our recent watches. The auctions are public, and the watches are verified by experts from the auction house and also often by us, because we are in connection and constant communication with the source. Auction houses such as Christie’s and Phillips often ask us to identify the watches, so we know what’s coming – that’s the easy way.”

Sometimes, watches come directly to them as they pass through the team’s hands through the restoration workshop. Vivas says, “Sometimes … we say, ‘We will have to ask the owner to sell [this one] to us, because it’s so important.’ Or it can happen the other way around, where people come to us [to] see if we are interested in buying their historical piece.”

The most difficult path is actively searching for a specific reference of the watch, especially when you have no idea where it might be. In cases like these, the idea of “the community" plays a double role – as a factor that propels the team’s exploration of the past, and as a resource in helping to search for these pieces. As Vivas and his team highlight, pieces that you thought might be forever out of reach and might never be seen in our lifetimes can appear in startling ways.

An intricately made automata ring that demonstrates the presentation of a music box, set in rose gold and complete with enamelling and pearl detail.

“Sometimes, for example, we will decide that now we have to try to find a second example of the reference 5159, the asymmetrical origin of the [Re]Master02,” Vivas says. “Maybe we have to send around 50 people to look for them around the world, and there’s nearly no chance of finding anything because it’s probably in a safe somewhere, sleeping for decades, and nobody knows where it is.

“But ultimately this network is a small community of retailers specialising in historical pieces. Everybody knows everybody. Sometimes we know this guy who knows another guy who saw it or heard about it, so the watch becomes a question that people ask to others who might know. So, if the watch was ever seen in the last 10 years in some collectors’ circles, we have a good chance of finding it.”

A jump hour example from the first half of the 20th century, alongside other examples of the period with unconventional cases such as tonneau or square with rounded edges.

Vivas also shares a heartwarming story about a time when history and timing coincided to result in the discovery of a piece no one believed actually existed. “When we did the book dedicated to complications, we found out that we could study the first Audemars Piguet Perpetual Calendar wristwatch,” he says. “We could say there were three with the moonphase at 12 and three with the moonphase at six, and the different variations. But we also found that there were three models without the leap-year indications, and we only had pictures of these. And we could not even be absolutely certain that they were perpetual calendars.

“We asked, ‘What is this? Something is missing. Maybe it’s a prototype that was never released?’ But no, it was shot, so OK, it was released, and it’s part of the story. And you know what? Maybe one day we will find it, but we cannot start looking for it. There’s no chance that we can find it.

“But then somehow, at the very same moment, a client went to a boutique in Bangkok [with] the watch on his wrist. He asked the salespeople if they knew this watch and said that his grandfather gave it to him. The salespeople replied saying that they had never seen something like that, and it was probably not a real Audemars Piguet. He sent the pictures to Le Brassus, and they said exactly the same. Never seen that before, it cannot be – a perpetual calendar like this from 1949-50 did not exist, so it’s probably a Frankenstein watch. Then it came to us, and we said, ‘Guys, we found it!’ The guy came to visit us and it was crazy, but fantastic. It’s impossible to find this kind of watch by chance if you’re looking for it.”

The story is a triumphant example of stumbling across a history that barely anyone recalls, that is made new by virtue of rediscovery. However, it also speaks to an entirely different culture of greater diversity, and a willingness to accept differences, something that has been lost in a society where the idea of standard production and “limited editions” have been turned into commodities under capitalism. Part of the team’s job is to discover these pieces we would consider outliers today, which have taken new significance assigned by the culture we live in.

The Audemars Piguet ref. 4274 “Zebra”, notably distinct because of its design and striped countenance, as well as its rarity.

When asked about “the watch that got away”, we can be sure that there are several that might come to mind. Vivas laughs when the question is asked. “Well, which one can I talk about? There are so many,” he says.

“One in particular is very important. It’s an ultra-complicated watch that was made during the First World War for Smith & Sons, and is somewhat like the Universelle at the centre of the museum, but even more complicated. We know it was shot in the 90s for a book that we have published, but we cannot find it, even now. This is one that we could, with the community, start to seriously search for in order to have it for the anniversary, and this one makes a lot of sense.

“There are also a few small minute repeaters from the 1920s that we are searching for, but otherwise it’s rare that we really go on the hunt, because we already have a great collection, and we are well equipped to tell great stories.”

Overall, there is an optimism about the entire endeavour that is not hard to see within the team. “I personally believe that most of these watches will come back one day,” Vivas says. “I’m quite sure that, having relaunched a watch based on the asymmetrical 5159, it’s possible that in six months or even one year, some people might think, ‘Oh, maybe my watch has a value?’ and they will come to us for restoration.”

A Science of Curating

In curating and selecting these pieces for their collection, they are not just documenting the history of Audemars Piguet, but of a wider culture and socioeconomic period. What we might consider to be the peak of exclusivity today was just seen as normal because society was more deeply entrenched in traditional craft, and tolerant of personal touches and differences between makers.

With their capacity for production only continuing to grow, and new watches being released every year, the challenge is to predict which watches will be historically significant to future audiences.

Walking among the different displays within the museum is an exercise in imagination as well as understanding as you think about the kind of person who might have owned this tiny clock set within a ring, or consider a family of perpetual calendars, demonstrating their evolution over the years.

Vivas says, “Exclusivity is really part of the DNA of Audemars Piguet. For 75 years, the brand only made unique pieces. So, if you had it, you are the only one to have it. If you sell it to someone, it will be the only one. It’s the top of what you can consider to be exclusivity. But on the other hand, it’s absolutely normal, because nothing is made in more than one piece. From the 1950s, we started to produce larger quantities, from five to 10, 15, 20. Then from the 1970s onwards the Royal Oak … was the first that was made in more than a few hundred – 1,000, and which became 4,000.

“What is more important? The ref. 5402 was made in more than 4,000 pieces, and it symbolises a milestone in the history of watchmaking. The 5516 perpetual calendar we were talking about was made in nine examples, all different from each other, and nobody remembered it because it took 20 years to sell them. On one hand, the collectors are saying, this has more value because this is rarer! On the other hand, a historian might say, well, historically, nobody saw them. It did not influence anything.

“Rarity for collectors has a different value compared to milestones in history. We are always trying to balance between being collectors and historians. While the collector might say this has historical importance because there were only two, the historian will say that this is absolutely meaningless, because there were only two. It’s a question of point of view.”

This approach – keeping the brand’s history and context in view while also having one eye fixed on the future – is also applied when considering which new releases must be preserved for the generations to come.

“We try to imagine what the next generation will remember or will consider memorable,” Vivas says. “It’s impossible, of course, because they may not appreciate what we consider today, but we cannot keep everything … We are mostly enriching our collection. I’m talking about the historical watches. They are historical as soon as they enter the heritage collection, although they might not even be launched yet. It’s a milestone in history. For example, the RD#2, which is a big milestone or the RD#4, which is key – we need to keep at least one example of these watches.”

Various factors come into play when deciding which of the older watches are worthy of entering the collection, Vivas says. “Sometimes the dial has a very strong meaning – it brings us back to an old know-how or it’s a new material, a new colour, or there’s a story behind it,” he adds. “A watch has to have meaning, and it has to tell a story. Sometimes, there is not much to say except ‘this is a new type of hand’, but that’s not interesting. Of course, there is always something to say, but it’s a question of balance.”

With so many watches, it’s almost impossible to give each one an equal amount of attention, but seeing how the individual examples fit together to tell a coherent story is just as important. Vivas says, “What I like [about our collection] is the diversity and the richness. There are thousands of watches, so some are very meaningful [so we will support their remastering]. And quite a few that we really love, we might say, ‘Well … there were only [one or ] three or seven of these; we should get inspired by that and do something today for a larger audience.’”

A rare double-signed example of a rectangular perpetual calendar, with “E. Gubelin – Lucerne” on the dial.

The Question of Restoration

A prototype of a self-winding tourbillon watch, made around 1985. Note the thinness of the case.

Once the watches are obtained, what’s next? Restoration is a sensitive topic in the collecting world, as the physical effects of time and the object’s experiences are also a kind of history. Some are of the opinion that this history should not be erased as it has become part of the object. However, when it comes to pieces that are for public education rather than for commercial sale, the stakes are quite different and the decisions about balancing its original condition and restoration are much more straightforward.

“We try to bring the watches back to their original condition as much as we can,” Vivas says. “Sometimes we don’t know what they looked like originally, but our dream and objective is to bring the watch back to its original condition. But we also keep what makes sense, such as patina, because history is part of the object.

“It’s not about renewing a watch, making it look as shiny and new as it did originally. Firstly, that’s impossible – if it’s been polished a few times, you cannot bring the material back. For example, the 5159 was very sharp, but now it’s very rounded. To make it sharp again, you have to reduce the thickness of the case even more. So, we keep the history, and we always look for balance.

“Sometimes we have strong discussions within the team, and we also have to discuss it with the clients. For example, if an original signature has been lost because the dial has been redone maybe 40 years ago – we don’t know where, we don’t know by whom – we have to bring it back, but we don’t know exactly what it looked like. We have to interpret this, because we don’t have the picture of this example. Ultimately, it’s about finding solutions together and it’s about interpretation, which makes it very interesting.”

But how does the team figure out what is truly “original” to the watch? There are several complicating factors at play, but ultimately context clues and experience help in deciding which interpretation of the watch they go with, while sticking strictly to traditional methods and original metals.

A glimpse into the complications workshop, and the 1899 Universelle, an impossibly complicated piece that lies at the heart of the museum.

It Takes a Village

While the archival work and restoration department shine in their work, the subtle touches of creating Audemars Piguet’s atmosphere and the air of luxury fall on the ground staff in the museum’s physical space. Despite visiting being a privilege afforded to few, the impact of the space and the people within it is significant, which Vivas underscores.

“There are many different departments that make the museum work, but the most important is the hospitality department, because they are in charge of welcoming visitors – whether they are the general public, journalists, clients, partners, or employees coming from Le Brassus or from the other end of the world,” he says.

“It’s about human relationships, and we [the heritage and museum team] are part of that, but not in charge of that. That’s really the hospitality side, which is connected to retail, to client services, and we also welcome people who come just for restoration.”

There is a real sense of a community coming together in celebration of a shared passion. As Vivas says, “What I like with the museum is that it’s at the [crossroads] of local and international, from internal employees to our biggest clients, and it’s very strange when you think of that happening in the small village of Le Brassus. People come from all over the world to discover AP, to meet us, and to enjoy high-end watchmaking – a very special destination.”

Seeing the Present Through the Past

In a previous article, we’ve spoken extensively about the transformation of the Royal Oak into a cultural icon of the modern era, but the Royal Oak is certainly not all that there is to Audemars Piguet. In recent years, the team’s work has made it on to a wider stage with the [Re]master series – two examples of which have already been released in extremely limited numbers. The thinking behind this transformation and reissue is especially interesting.

Asymmetrical watches represent a fairly small chapter in the history of Audemars Piguet, but the phenomenon captured the imagination of many at the time, as we’ve also explored in a previous article. These variations weren’t just limited to Audemars Piguet but can be seen across brands like Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Cartier, and others.

Before the recent release of the [Re]Master02, as they were still figuring out the brand’s history during this period, Vivas describes the experience of trying to find out exactly how many asymmetrical watches Audemars Piguet issued during this era. “We had no idea about the number of asymmetrical pieces and number of references at first,” he says. “But we discovered that in four years, 30 references were produced.

Likewise, the [Re]Master01 took direct inspiration from the reference 1533, a chronograph from the 1940s of which only three were ever made, in different metals. The brand asserts that these are not just simple reissues, but remasters, seeking not just to copy the original, but to take the concept of it and try to do something new.

However, the modern take on a watch like this ultimately represents the industry’s reliance on these historical pieces in terms of design inspiration. There is a distinct sense that something is missing today, and the [Re]masters – alongside other attempts to revive vintage style watchmaking, both mainstream and independent – have made it painfully evident that watchmaking today just isn’t as interesting as it used to be.

Similarly with the museum, looking at the breadth and depth of what the brand used to create, there is a vibrant sense of creativity and self-expression, and a real sense of the cultural era. The constant need for instant gratification that pervades our generation is somewhat at odds with this idea of timelessness – the chasing of the next exciting thing often leads to a desert of anything truly groundbreaking.

As a parting note, we invite you to reconsider the role of the museum and the impact its pieces and displays have on how we see our current world. This collection is crucial to the preservation of history but, aside from reissues and remasters, what other forms of inspiration can it bring? In 150 years’ time, which watches and designs will be remembered, and why? What kind of legacy will be left behind or deemed worthy enough to preserve? Most importantly, what kinds of stories will be told? The future is impossible to predict, and there will be more questions. Only the passing of time can reveal the answers.

This article was independently produced purely out of our interest in the subject, and we thank the Audemars Piguet Heritage & Museum team for their time, including Sebastian Vivas for patiently answering our questions, Mark Schmid for guiding us around the museum, and Laura Marino for facilitating the visit.

Photography by Jana Anhalt.