The Morteau Makers: What’s Next for Alexandre Hazemann & Victor Monnin?

Kwan Ann Tan

Alexandre Hazemann and Victor Monnin are part of a new era of independent watchmaking. Freshly graduated from the prestigious Lycée Edgar Faure Morteau, an academy that has seen quite a few of its students over the years distinguish themselves, they also made waves after working together on the winning watch of the F. P. Journe Young Talent competition of 2023.

The story of their partnership is a heartwarming one – they went from being friends in the first year of watchmaking school, to becoming flatmates and collaborators on their school watches, which are notably powered by the same mechanism. They credit their closeness and shared drive for their project's success, while their distinct personalities are evident in their two school watches.

In this interview, we uncover the story behind the matching, custom-made blue work coats that are a symbol of their friendship-turned-partnership, as well as the thinking behind and process of making their school watches, which was so intensive that they turned their shared student flat into a workshop.

ACM: First, let’s hear about how you got into watchmaking, and why?

Alexandre Hazemann: For me, it all started́ at the age of 13, when my father came home from work with a prototype watch by Michel Parmigiani on his wrist. I looked at the back - it was open - and saw the whole mechanism: those wheels, pinions and to-and-fro of the balance wheel. After that, I decided to take an introductory course at the watchmaking school in Morteau, and I knew it would become my lifelong passion. This watch was the trigger for my fascination with watchmaking.

Both Hazemann and Monnin come from watchmaking families, a legacy that sparked their interest in the craft and encouraged them to join the profession.

Victor Monnin: I come from a large family of watchmakers. My great-grandfather and grandfather founded the eponymous watchmaking company called Georges Monnin, which they ran for around 45 years.

Growing up, I heard many stories about my grandfather's company and its watchmakers - he was instrumental in saving the faded Heuer brand in 1979 with the introduction of the Heuer Monnin Reference 844, bringing unprecedented success to the brand. Heuer became Tag Heuer after the brand was acquired in 1985. For me, becoming a watchmaker was a natural step.

You both attended the Lycée Edgar Faure Morteau. What was the curriculum like, and does the school have any particular focus when it comes to watchmaking?

AH: First of all, it's important to know that the Morteau school is one of the few to defend and teach the values of artisan watchmaking. The apprenticeship starts with the basics: filing, hand-turning small components and assembling watches. After that, we learn to draw, design and manufacture watch complications.

VM: The Morteau Watchmaking School emphasizes a creative way of learning and developing your own watches. As early as the third year, during the Brevet des Métiers d'Arts, we had to demonstrate a high degree of autonomy to complete our first projects. You also have to get to know and tame conventional machines like the Schaublin 70 lathe or the Hauser pointing machine. You experience the apprenticeship as a craftsman, it was the beginning of watchmaking independence at school.

ACM: When it comes to the school watch that you have to make upon graduating, did you already have some idea of what kind of watch you were going to make?

AH: This watch was the fruit of 10 years of watchmaking learning and culture. I knew what universe I wanted to give my watch. I had ideas engraved in my mind that I couldn't forget or let go.

ACM: How did you two meet at school?

VM: We began our friendship and collaboration long before our final year of school, of course. During our first year of study, we were regularly assessed on grading, sawing, making small watch components and fine-tuning mechanical movements. These tests, which often lasted 8 hours, were very intense. We soon realized that we were the last two students to leave the workshop. We wanted to use all the time we had to make our work as perfect as possible. Our friendship grew out of the realization that we shared the same work philosophy, and has continued to do so in the 7 years since our training.

The first time we worked together on a watchmaking project - it was a complicated watch with a retrograde function. We were only about 17 or 18 at the time. After that, we wanted to do it more professionally, with our school watch.

According to the rules, you have to work alone to get your diploma, and then by nature you have your own ideas and styles, of course, but our friendship was stronger and we knew that through a shared passion this could only lead to surpassing ourselves to succeed.

Their shared philosophy and respective strengths have brought them together, not to mention their enduring friendship and spirit of brotherhood.

ACM: What is your collaboration like? What’s the process of making something together?

AH: In a way, it all starts with our friendship. It's a lot of talking and sharing inspirations. Honestly, we talk a lot - maybe thousands and thousands of hours! We've created a real framework to galvanize all our energy towards a common goal.

VM: It’s difficult to work alone on projects like these, so that’s why we decided to work together [on the school watch]. It’s easier when you can share things with another person, and it’s cool to have someone to be excited about things together with.

ACM: What inspires both of you?

AH: We love artisanal methods - the true savoir-faire of the watchmaker, and we admire many independent watchmakers. But more and more, we find inspiration in vintage pieces. We particularly like early Patek Philippe, and find it very interesting. Breguet too, and Antide Janvier.

I can also add that my inspiration and desire to create this watch also stem from a great admiration for old school pieces, very well illustrated in a book that marked my youth: Dix écoles d'horlogerie Suisse - Chefs d'œuvre de savoir-faire. The desire to belong to this heritage became an obsession for me.

VM: During our school years, we had the opportunity to work in some of the workshops of independent watchmakers such as Julien Tixier, Simon Brette and Sylvain Pinaud. In a way, these moments helped inspire us and teach us a constructive vision of watchmaking.

ACM: How did you perceive the school project at the beginning?

AH: When you enter watchmaking school at the beginning, you’re quite young. And you see the older students, those who are in their last year of study – you see the school watches they make, and you say: “Wow, I need to make one too.” You think about it every year, and during your final year, you know that your time has come – this is the year. So you are well-prepared to make one, and it takes up all your focus during these nine months of school.

VM: I think it’s the best motivation to see the older students and their work. When we started, Julien Tixier was in his final year, and he was really cool to us and a big inspiration. And because you work a lot when you are in the final year, you want to be someone like him ¬– someone who’s 22 years old and has all the skills. Watchmaking school is not just about watchmaking – you are also the technician, the jeweller, etc. So you are really independent.

“We like artisanal methods – the real know-how of watchmaking, and we admire lots of independent watchmakers. But increasingly, we find inspiration in vintage pieces.”

– Alexandre Hazemann

ACM: How did you work together on your school watches?

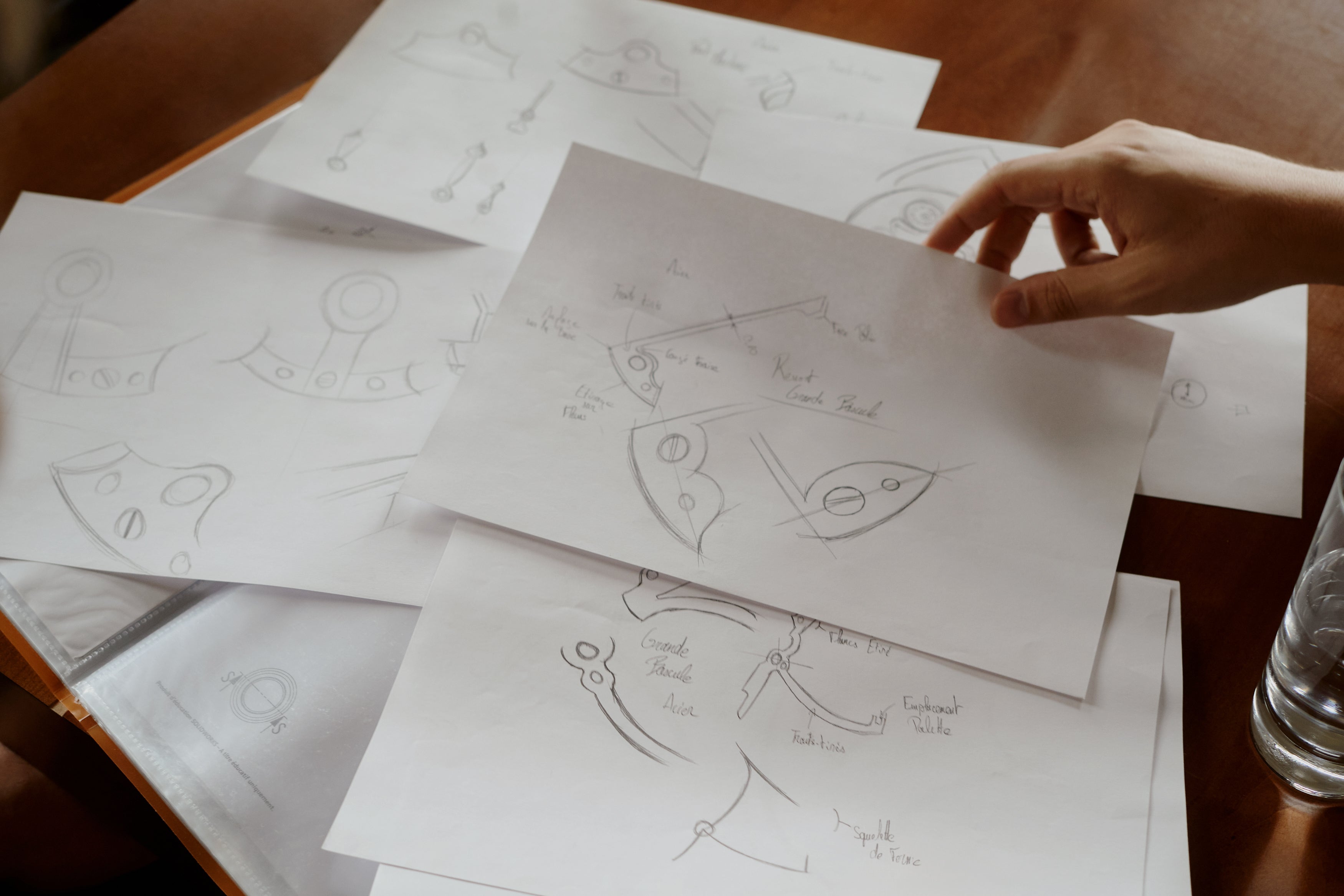

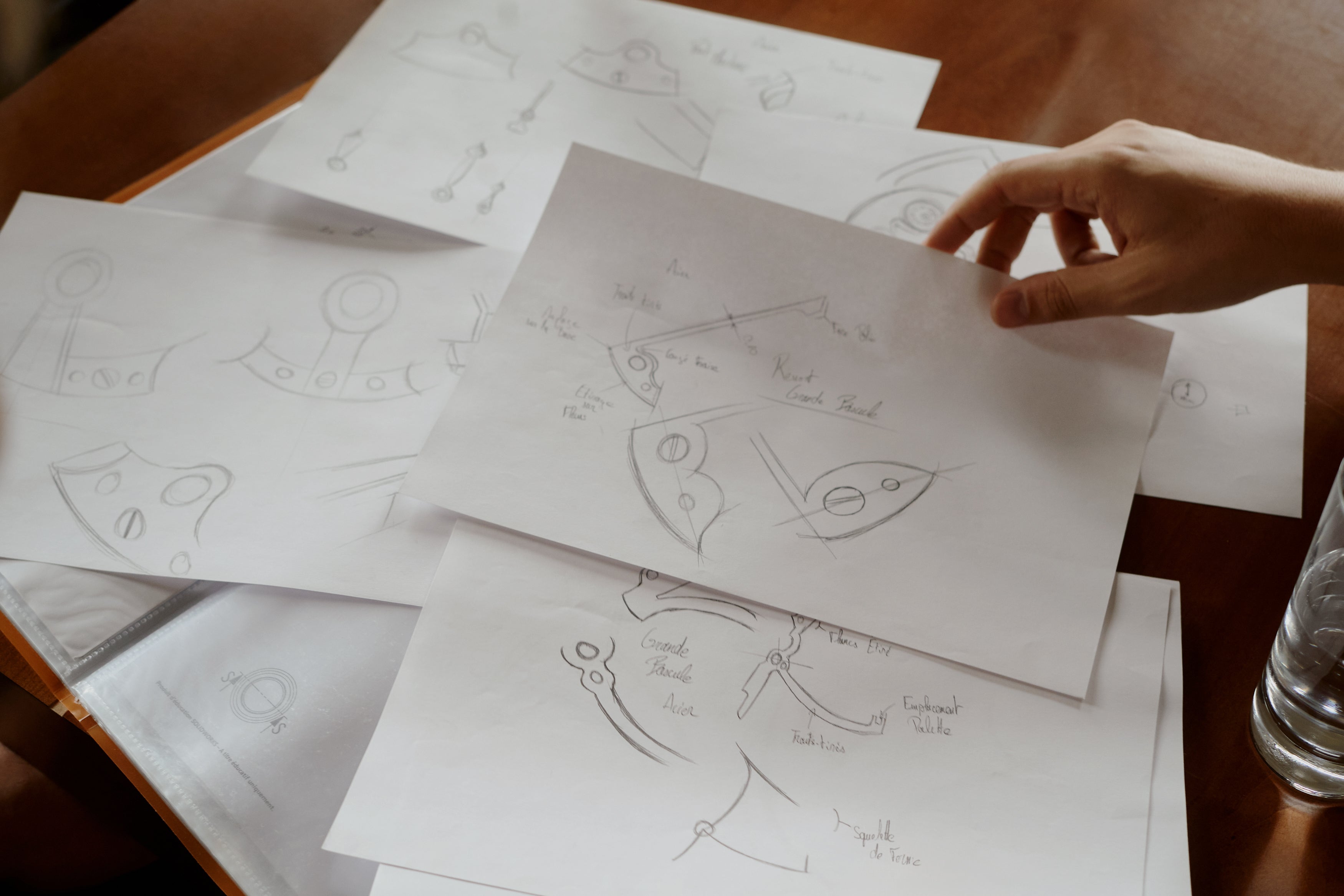

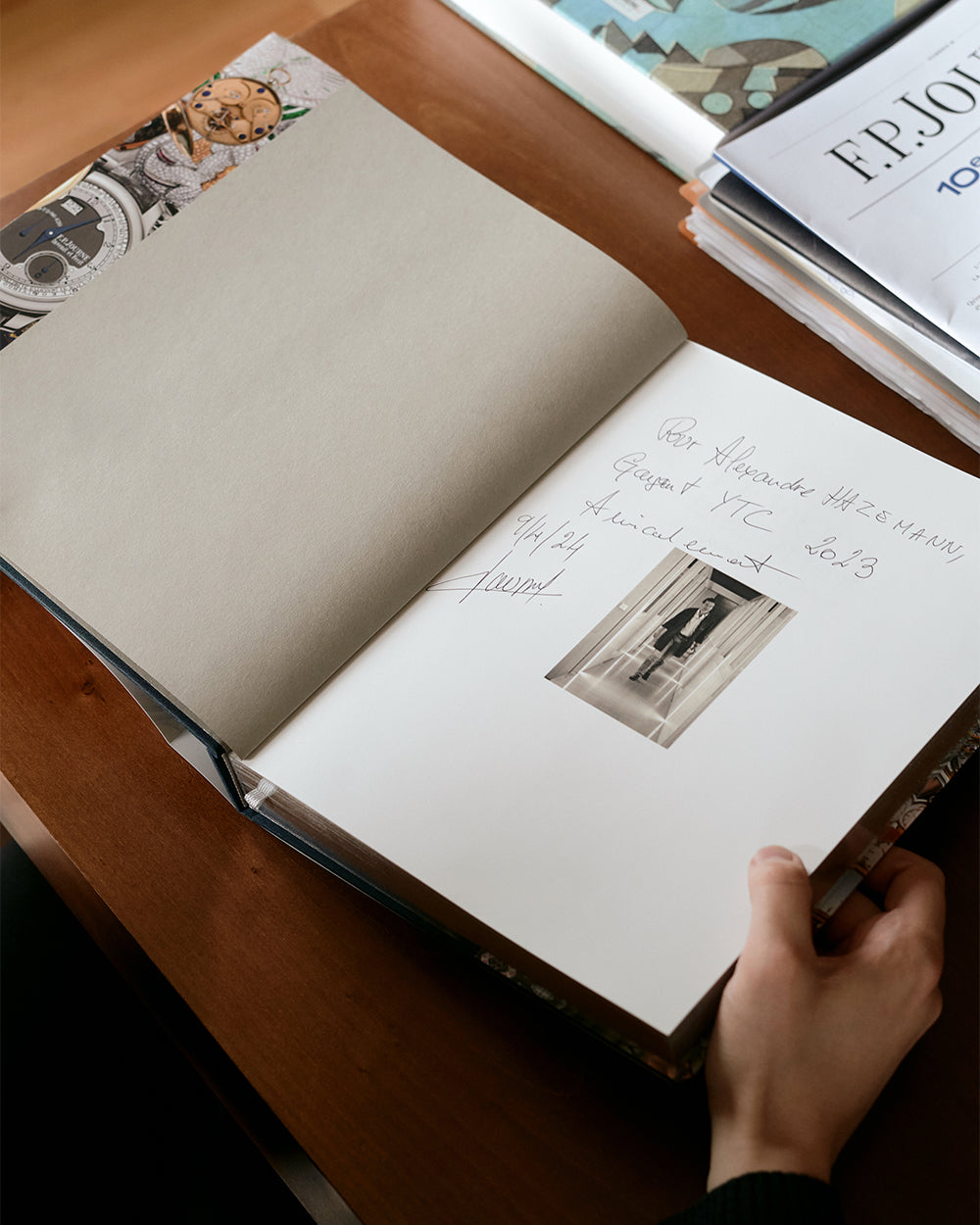

AH: In that last year, we were really like independent watchmakers. We had also lived together for the last three years of school, so in the living room we removed the sofa, and that was our workshop. We put our computers together to make a workspace; we put a bench in the room, and the machines. We worked together at school, and then after school had closed, we went back to our apartment and worked there. We even made our own watchmaking coats with our embroidered initials! So we would be at school, working in our own uniforms.

VM: Watchmakers usually wear white coats in the workshop. At the time, we wanted to differentiate ourselves by having our own blue coats made (less messy during the oil splashes from machining) and with the inscription “AHVM” featuring our respective initials. At the time, we wanted to experience this joint adventure as two independent watchmakers.

ACM: After school, what did you go on to do?

VM: After school, I was contacted by a very discreet artisan workshop based in Switzerland. My desire to work after 7 years of apprenticeship was stronger than ever. The position of young watchmaker prototypist appealed to me immediately, and I was ready to invest myself in professional projects surrounded by experienced craftsmen.

AH: After completing 7 years of watchmaking studies, I chose to continue my training in the development and creation of watchmaking complications. So I decided to join a specialized school in Switzerland in design in order to gain more cards in my hand so that I can build and develop future projects with Victor one day.

The school watch represents a culmination of almost seven years of study, with their collaboration allowing them to create a more impressive project than they might otherwise have individually.

ACM: The aesthetics of your school watches are quite different – what was the thinking behind your choices?

VM: To start with, we made a lot of drawings. A lot, because after seven years, this was our last project and we'd never done one this complicated before. So, although we had a lot of ideas, a lot of inspiration, we had to put all these ideas on the table and choose one, which was really difficult.

Personally, I really like older styles, especially older styles of interior design. I found a lot of references in books, and I really liked the Castiglioni brothers' work. I also really like MB&F, and I liked the malachite stone on their ladies' watch [the LM Flying T Tourbillon].

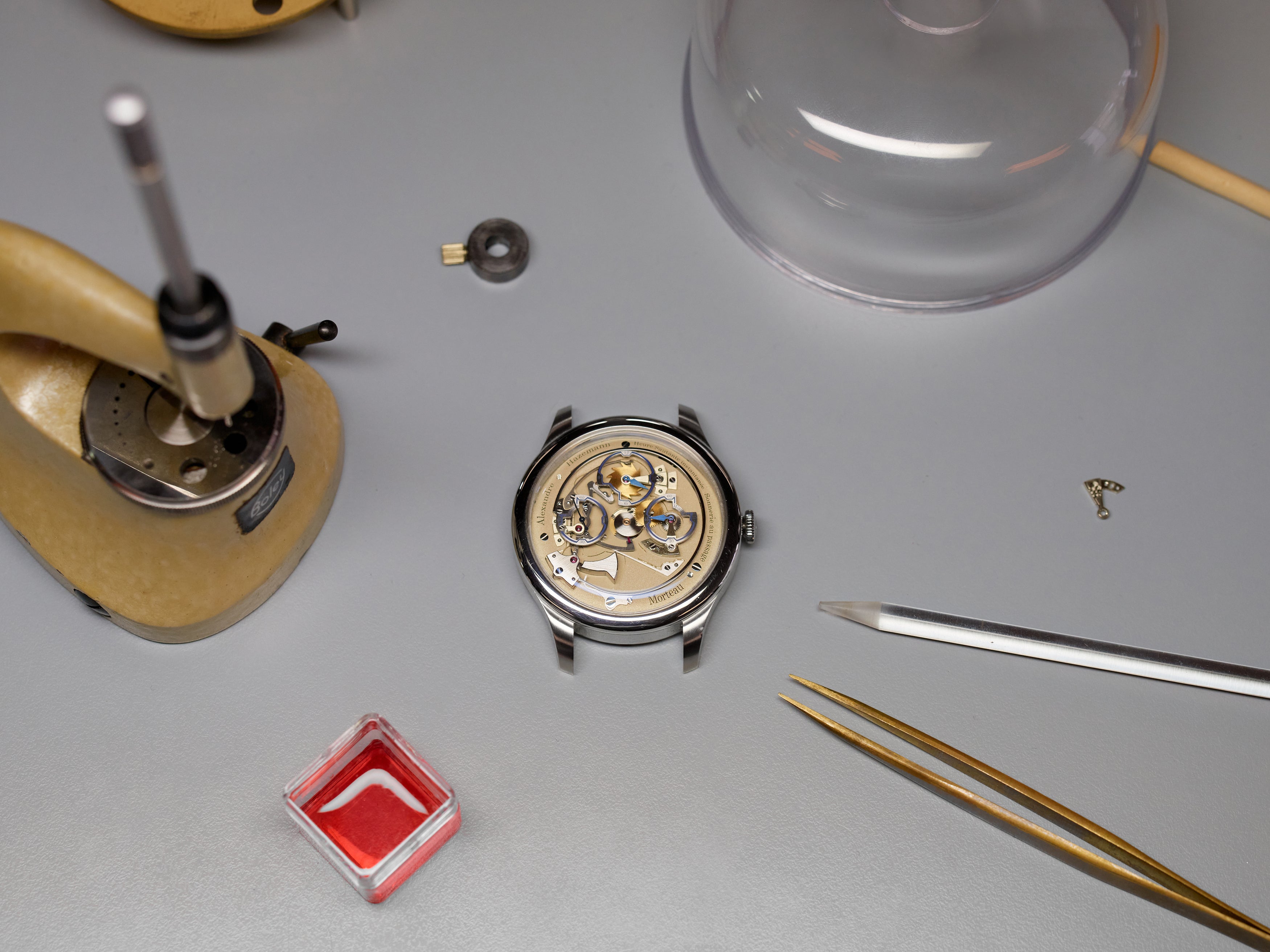

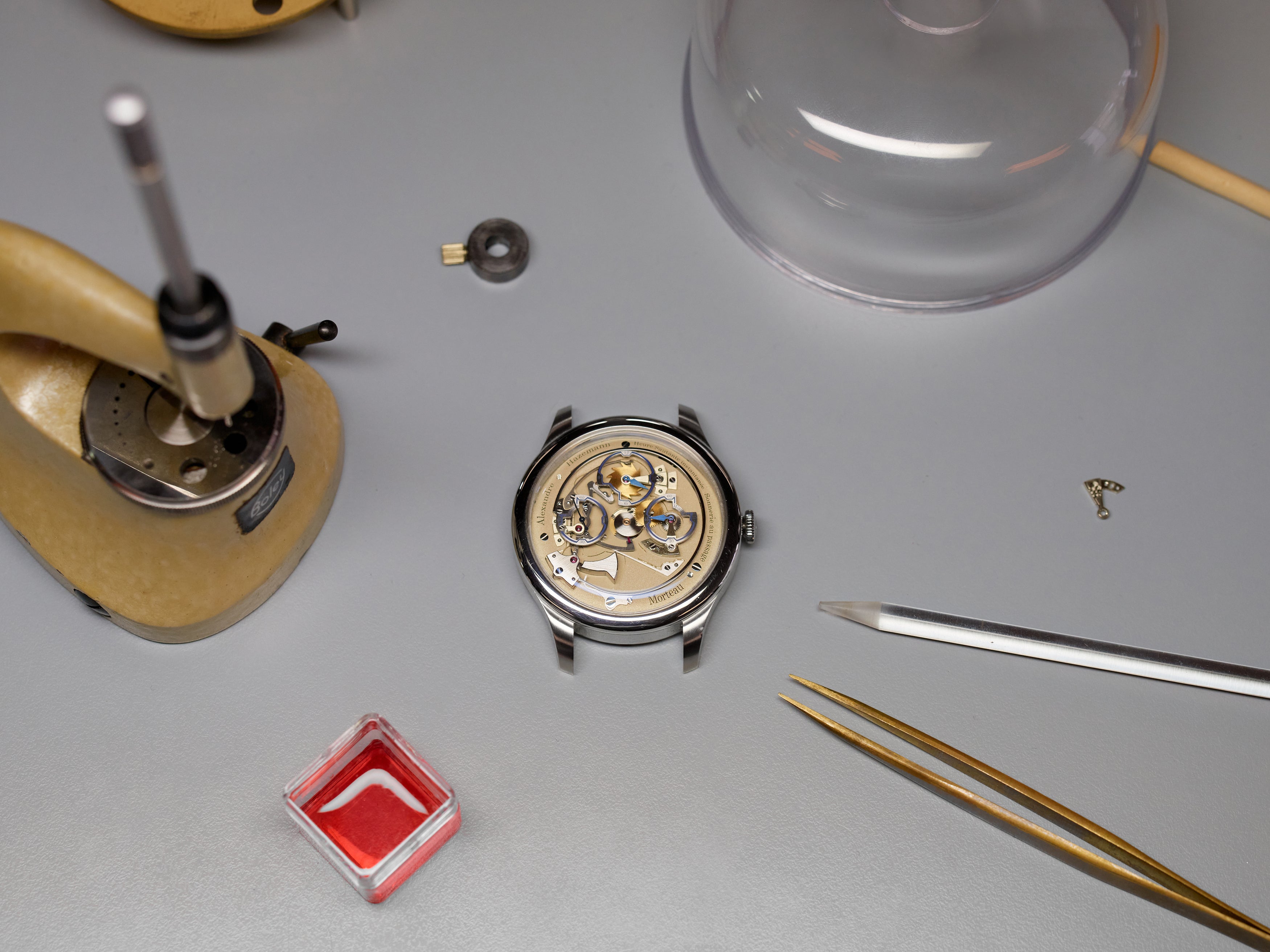

Basically, my watches and Alex's have the same mechanism, with the chiming hour, and all the other parts are the same.

AH: Right from the start, I grew up discovering the creations of independent watchmakers in the magazines my father bought me. François-Paul Journe was my greatest source of inspiration. What I like about François-Paul's approach is that, at a time when most watchmakers were reluctant to make complicated pieces, he was more focused than ever. He was the kind of man who would tackle anything technical and see it through to the end.

For my watch, I decided to do open-ended work. That's my philosophy when it comes to watchmaking, and my own language for expressing my love of fine mechanics.

Today, the pair are respectively growing their skills, continuing to brim with ideas and future collaborations in the far horizon.

VM: On the caseback of my watch, there is a map of the city of Napoli – an important city in Italy because it’s a cultural centre for design and history. I was thinking about Italian style from the 50s and 60s, and a big thing for me was the intemporality of style across this period.

AH: I chose blue for my watch because of steel. When you temper it, the steel becomes blue, and I love the blue that appears at the beginning. When you match the strap with the colour of the interior of the watches, I think it’s very interesting. For both of us, we didn’t want to be classical at all, so we didn’t choose black or brown straps. We chose our straps at a factory in France, and even chose the exact part of the alligator that we wanted our straps to be made from.

ACM: What was the most difficult part about creating these watches?

VM: Time. You have about nine to ten months to do everything from scratch. You have to draw, design, build, prototype, decorate. When you have such a short deadline, it has to be good almost immediately, because you can't redesign everything over and over again. So we had to work smart.

AH: We also made the watch case on traditional machines, which is a big part of the project that took us 2 weeks. The challenge is also to find a supplier to make the straps and the sapphire crystal. Although you make the parts, you can't make the glass yourself. Although, for graduation purposes, it's acceptable to simply have a mechanism in a plastic box that can't be worn on the wrist.

ACM: Is the chiming-hour complication a typical thing a student would tackle for their final project?

VH: A chiming watch at any level is an extremely difficult complication to achieve. It has been the subject of exams twice in the last 20 years and has never left students with fond memories. The steel has to be worked into the right shape, and then posages have to be made to heat it to 830° without deforming it, which is a real challenge in itself. Then we have to file the base by hand to get it tuned to the right note for our ears. The most difficult part of our year was synchronizing the chiming with an instant time jump!

ACM: What was it like to win the 2023 F. P. Journe Young Talent Competition?

AH: The first thing I felt was a great sense of pride. After more than 1,500 hours of work on my watch, I had achieved all the necessary conditions to offer a product that I felt was relevant. I remember that day like it was yesterday, the day my phone rang to tell me the big news: we'd won, after all that effort, all those sleepless nights and weekends behind the workbench. Sharing this with Victor was a double victory for me: that of having accomplished a part of our common dream. What's more, to be rewarded and encouraged by François-Paul Journe, my spiritual mentor, the man who inspired me from an early age, was the ultimate consecration I'd been dreaming of for so many years.

ACM: What kind of watches do you want to make in the future? What’s your dream?

VM: My dream is to one day develop a masterpiece, something like Philippe Dufour did when he started to be an independent watchmaker, from his grande et petit sonnerie minute repeater wristwatch. I think it’s good thing that we started with a simple chiming hours for our school watch, and one day, we might be ready to make a really challenging chiming hour watch. When that day arrives, it will be interesting to reflect back on how far we’ve come.

AH: Ever since my early years at watchmaking school, my dream has been very clear: I dream of becoming an independent watchmaker. After a decade-long friendship, most of which was spent in the workshop with Victor, my dream would of course be to build it with him. This dream goes hand in hand with a desire to create mainly complication watches: from minute repeaters to perpetual calendars to double-balance resonance watches. As watchmaking is a blend of aesthetics, technique and philosophy, we can thrive on any complication.

Our thanks to Alexandre and Victor for sharing their histories, thoughts, and processes with us.

Photography by Jana Anhalt.