The Morteau Makers: What drives Théo Auffret?

Raj Aditya Chaudhuri

The location of Lycée Edgar Faure – the French watchmaking school in Morteau where 28-year-old Théo Auffret gained his formal education as a watchmaker – is such that after graduating from it, the vast majority of its students make the short trip over the border to Le Locle in Switzerland seeking work. This is because France, once a hub of watchmaking, is no longer a centre for the craft.

While the country has continued to provide a steady flow of watchmakers to Switzerland over the years, we are beginning to see a new wave of young makers more minded to create in a style native to their homeland. Several of these watchmakers are alumni of this very school in Morteau.

Over a series of interviews, starting with this one with Auffret, we will dig into the distinctive French school of watchmaking, its technical basis and particular style of finishing, and try to understand if fine watchmaking in France can experience a resurgence.

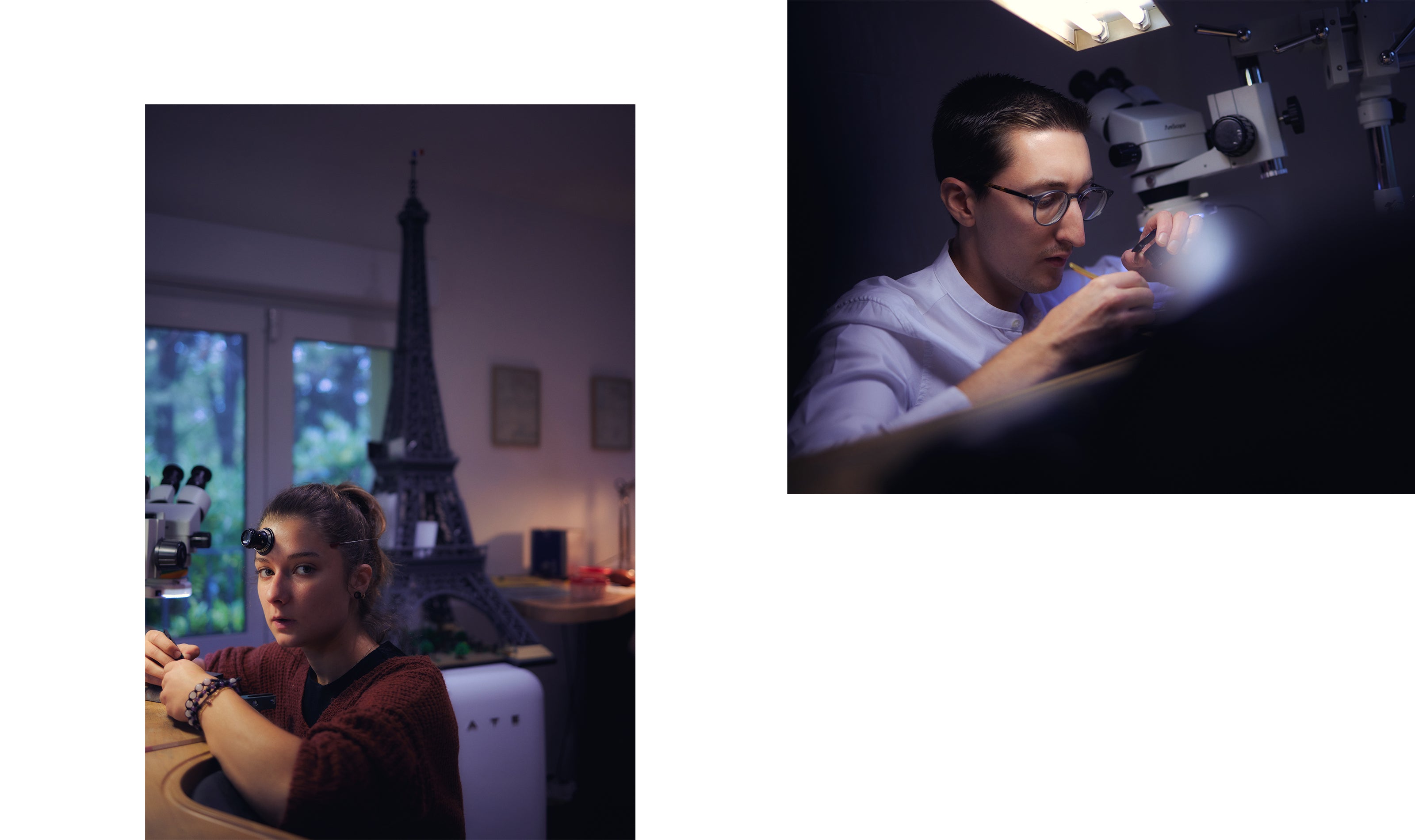

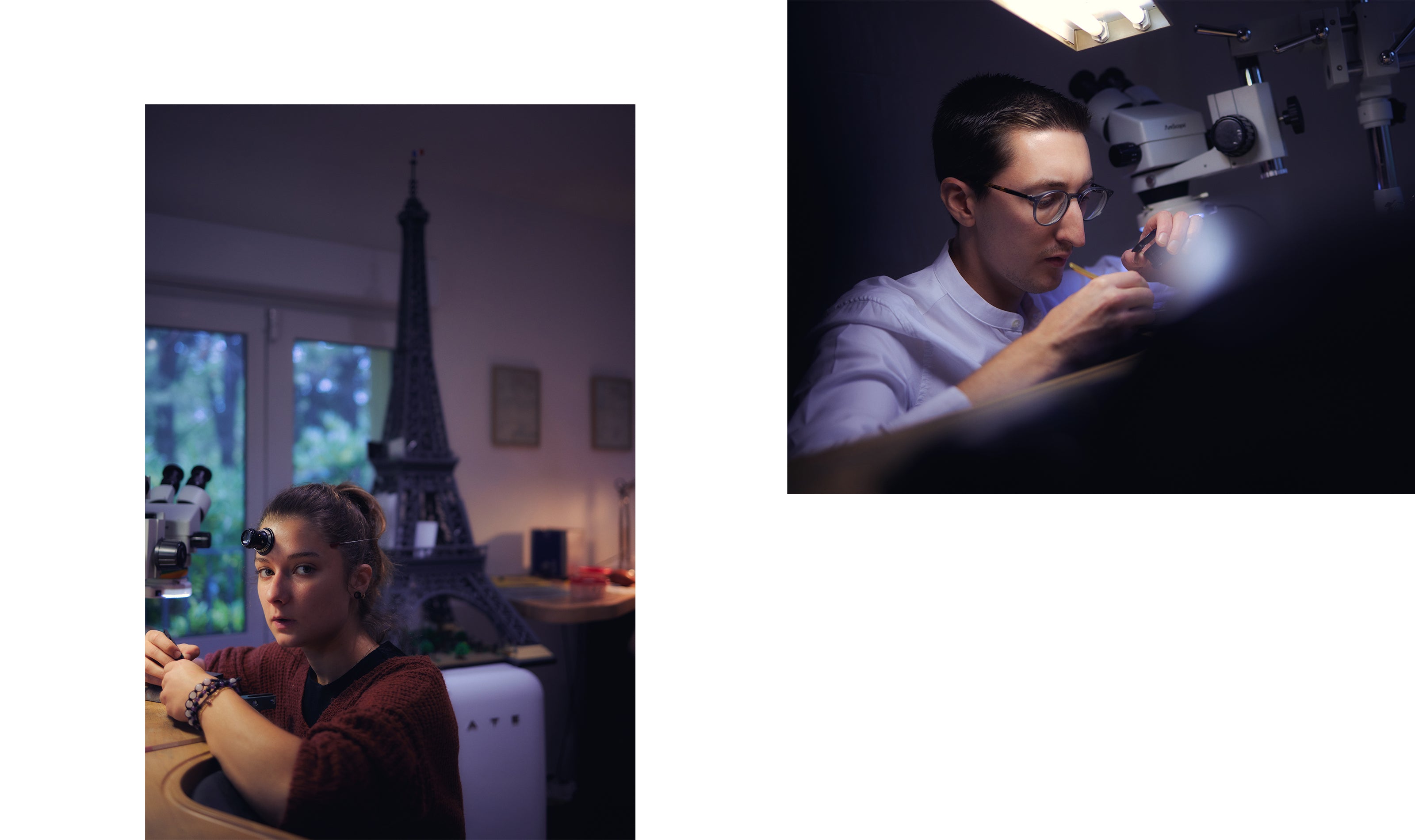

While showing us around his workshop in the Paris suburb of Poissy, Auffret talks about how he found out about independent watchmaking when he chanced upon photographs of two pocket watches made by François-Paul Journe, and how his story came full circle when he won the F. P. Journe Young Talent Competition. He tells us why he decided to come back to France and how he relishes his role as Paris’s sole independent watchmaker.

A Collected Man: What was it that motivated you to pursue an education in watchmaking?

Theo Auffret: I was a very calm and quiet child. I’ve got three little brothers and I’m the eldest. My education was a very classical one; I went to college and studied the typical mathematics course designed for a scientific baccalaureate. As my course was coming to an end, I had to choose between going to university or engineering school. I don’t remember exactly how it happened, but one day my father went to a watchmaking boutique in Paris to buy something and I went with him. I am not sure what connection it made in my mind, but I kept going back again and again to see the watchmaker there. Finally, in the last year of my baccalaureate, the watchmaker there allowed me to come one weekend and work with him.

I went one day and just never left. I was spending all my time in this boutique’s workshop with him. So, when I finally had to decide on school, I chose a path that was a more physical one and allowed me to work with my hands. It's something that has always mattered to me. I made a lot of [model aeroplanes] when I was young, and I have always been interested in the mechanics of motor cars and motorcycles.

I was not that motivated by engineering school – maybe I was a little bit lazy, and it didn’t seem as sexy because I didn’t want to do something that everybody else was doing.

Your education as a watchmaker was influenced both by the school you went to and the masters you apprenticed for. Which of these do you think had a greater effect on you?

When I went to [watchmaking] school in Morteau, I was a little bit older [than the other students]. In France, when you go to technical school – we call it technical or professional school – [students tend to] start at 15 or 16 years old. I was 18 just after my baccalaureate, and I was already more skilled than the young students due to my scientific education.

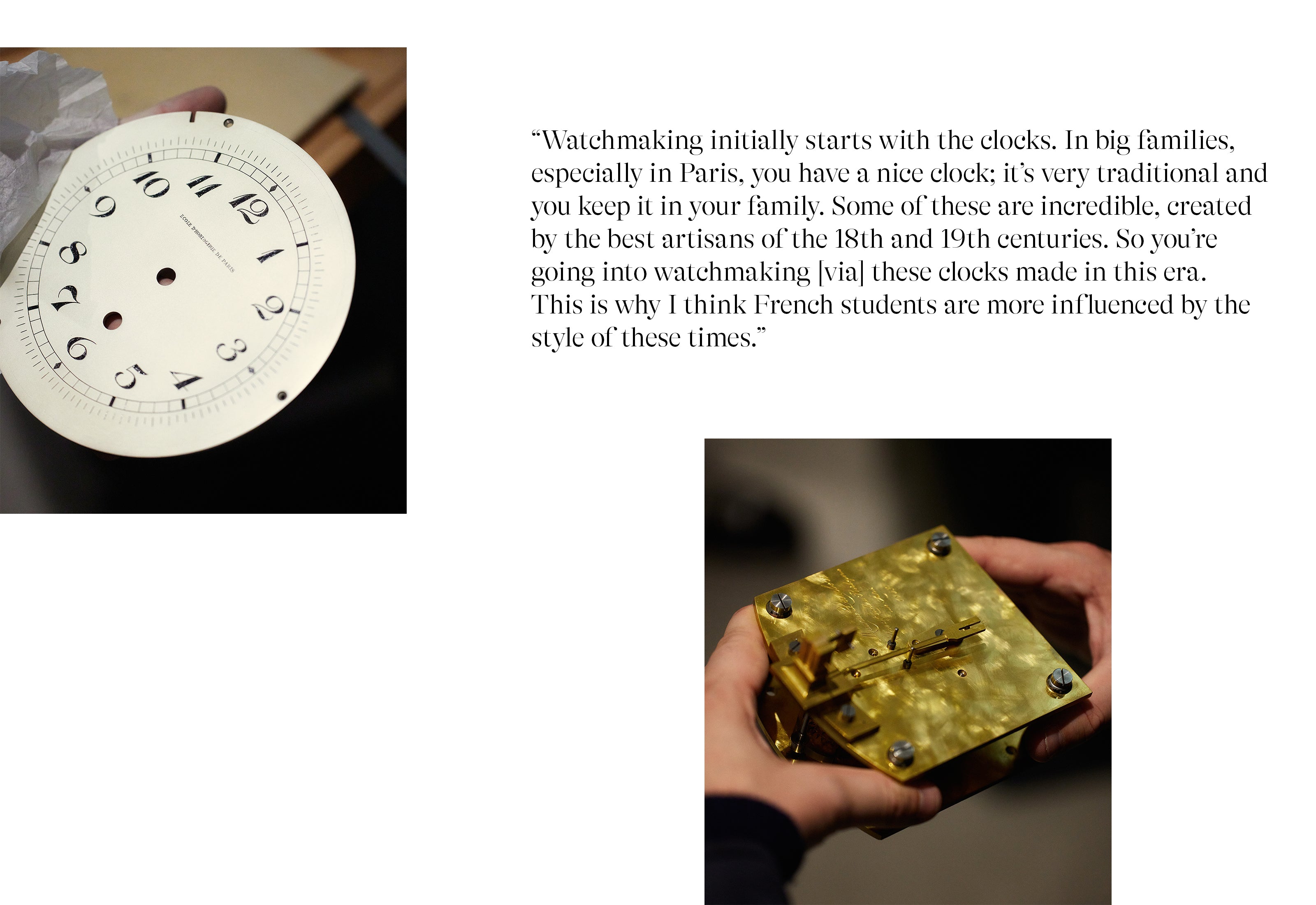

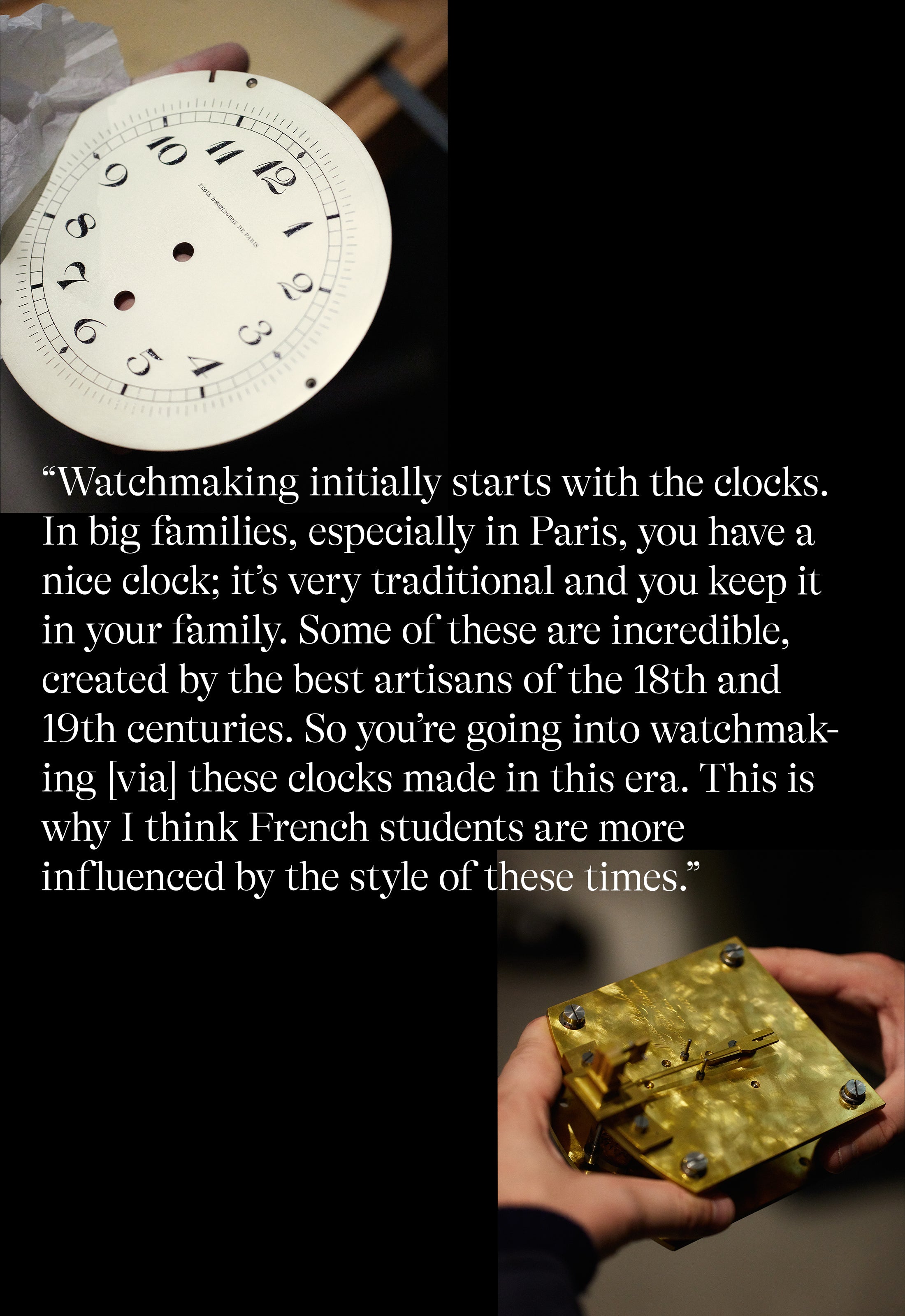

I decided to go to watchmaking school by way of apprenticeships. I found one in a boutique in the centre of Paris and started with clock restoration, something I did for two years, working for Denis Coperchot. I worked at his workshop by Gare Saint-Lazare in the centre of Paris. I discovered the work and creations of independent watchmakers when I found two old pictures of pocket watches. When I asked my master about them he told me about these watches Francois-Paul Journe made in the 80s. That was the first time I found out that a few people were still making watches by hand. [At] that moment, I discovered the world of independent watchmakers.

I also came upon this book titled Horlogerie Française [by Bruno Cabanis]. On the cover of this book is a watch by Jean-Batiste Viot; the very first chapter also is about him. So I [not only] discovered that such craft … existed, but [that] an independent watchmaker was creating right here in Paris.

I went to see Viot and asked him if I could continue my apprenticeship with him. He accepted, and I spent three years with him, helping him finish his series of wristwatches. He taught me everything that I know now. He’s not into this modern way of crafting [watches] – he does not have a computer – [so] all the plans of the watches are done by hand. I also did the same thing with the Tourbillon à Paris and even today we’re trying to work with these traditional drawings.

Almost as soon as I had become aware of independent watchmaking, I was making handmade watches for clients from all over all over the world. These were my very first steps into the world of independent watchmaking.

A bust of Abraham-Louis Breguet that sits close to Auffret's workbench, serving both as reminder of the weight of history and a source of inspiration.

Your education opened your eyes to independent watchmaking and winning the F. P. Journe Young Talent Competition in 2018 was another landmark moment in your career so far. What was that experience like?

I always liked contests. In fact, I took part in many when I was young. I won my first contest in artisan crafts in my first or second year of school. Such competitions are quite common in French schools. A contest is helpful because it tests your skills but also gives you a deadline, something that I like and need to have to motivate me.

I wanted to enter my tourbillon, which I was working on at John-Baptiste’s workshop. I was happy [with the outcome] and it was nice to see people from the industry looking at the piece and saying that it was not that bad.

Like many young graduates from Morteau, you then moved to Switzerland for work but returned to France soon after. Why is that?

After the Journe prize, I worked for a year and a half in Switzerland with Luca Soprana, working in prototyping [and] creating pieces such as the Astronomia Maestro Minute Repeater. However, Switzerland wasn’t made for me because I’m a Parisian kid – my family is here, as are my girlfriend and friends. I had grown up in a place that was calm but totally linked to the energy of Paris. For me, it was too difficult to be far from it. Switzerland was too calm for me.

While Auffret recently expanded the workshop currently locatedin the suburb of Poissy, he is planning an imminent move to a space in the historic watchmaking heart of Paris.

Given your experience up until that point, was going independent a foregone conclusion?

Even in watchmaking school, it was very obvious that some young watchmakers were more into creation while others were more focused on starting a career at a big company.

The first group – I like to say the “nerds” or “geeks” – these young guys [were] focused on creation. They [were] drawing a lot, reading books about Breguet, buying tools, trying to build things by hand. I think I was part of this category and I have some friends that are [too] – guys who went on to set up their own workshops. I am thinking of makers [such as] Remy Cools, for instance. However, at the end of that journey [at watchmaking school], not so many ended up setting up their own companies or workshops; those who did were quite rare. This is reflected in the fact that there are very few watchmakers under 30 years of age who set up their own brand and created something that collectors are interested in.

These were all things I was considering at the time, and I decided to take the position working in prototyping at Luca’s.

So what led you down the entrepreneurial path eventually?

When I came back to Paris, within six months the COVID-19 pandemic happened. For six months I was looking for a job – I didn’t exactly know what to do. I considered maybe becoming a watch and clock restorer. I love restoration, but more or less just for myself, working on the clocks and watches I collect. I considered offers from the big groups [such as] LVMH and Richemont, but I was not interested in the salaries they were offering.

I was wondering about my first creation, the watch I created for the Journe contest, that was not fully finished. I thought maybe I could do something with this. I had nothing to lose – no children or house to pay for. I was doing some restorations to get enough money to buy food and put fuel in the car. I asked my parents if I could stay at their place then so [I wouldn’t lose] any money to rent and they even agreed to let me turn one of their rooms into a workshop. They were very supportive and confident in my skills although I think it was quite strange for my parents and they wondered, “What is he doing?”

I spent about eight months working on my F. P. Journe contest prototype, turning that into something that could be the prototype of a series. In parallel I was also making all CAD drawings of the Tourbillon series subscription, all the plans and calculations about the costs. When I see them now, I realise how rough those calculations were. But I did this and sent a few pictures of the watch to some journalists I know, [such as] SJX.

That watch, which A Collected Man sold recently, became the 00, the first watch I sold. I originally had three orders for the Tourbillon à Paris. Then in January 2021 I had a positive article about the watch on Hodinkee and within one week I received 20 orders.

Auffret has taken a slow and considered approach to growing the atelier. With watchmakers Eve Albanesi and Nathan Trémion able to create independently, the atelier is poised for growth, Auffret says.

That must have been such a rush. Were you under pressure to scale up quickly?

Everything changed when I received all of these orders and then I started to think about hiring. Nathan [Trémion] joined the team and we decided to take [a] little space in Poissy to set up the workshop.

It developed very slowly, but that is the main philosophy here – we are trying to do our very best work. I think the quality we have achieved with the Tourbillon watches now is much more developed than the early days; the team is ready now to work alongside me and can perform some tasks independently.

This is something I have tried to communicate to collectors and retail partners, and it is the reason you won’t see my watches everywhere … For more than two years we have been focused on setting up so we can deliver the best quality. We want our first 15 watches – 13 Tourbillon à Paris and a couple of Tourbillon Grand Sport – to be really, really well made. I don’t want to have anything on the market that I’m not really proud of.

What is occupying your mind now?

I am really invested in the storytelling of the whole journey [experienced by] collectors buying a watch … because it isn’t like buying just any item. For many collectors, I think the best part of collecting is the moment they find a watch and watchmaker and decide to get it. They then go through this incredible period of discussion with the watchmakers, placing the order and then waiting for it. I always considered the waiting period as the best part of the journey. This is probably the reason why so many collectors, as soon as they receive a watch after a period of waiting for it, immediately place another order and start the process all over again. It’s a bit like the wait for Christmas.

So, the magic comes from the moment you imagine the product [and] anticipate it. Then it arrives, much like a new baby. I am working on telling the story of that journey more effectively.

We are also focused on setting up a beautiful workshop in Paris, especially because we will be the only watchmakers in the city. I think it would be incredible for the collectors to land in Paris and spend some time there with their family and then come to visit our workshop around the 1st or 2nd arrondissement. You can imagine how proud we will be to set up a workshop that will be only a few streets from the original Breguet workshop and share in the legacy of these fabulous watchmakers who were based in Paris around that time.

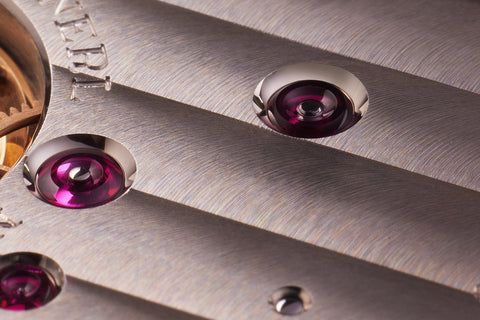

Charbonnage, a finishing technique where charcoal is employed to create a soft, hazy finish is one that has been the hallmark of makers such as Viot and Auffret. The latter employed it even to the watch he created jointly with Petermann Bèdat for Only Watch 2023/24.

“You can imagine how proud we will be to set up a workshop that will be only a few streets from the original Breguet workshop and share in the legacy of these fabulous watchmakers who were based in Paris around that time.”

The watches you create have a distinct French quality to them. What in your view marks them as such?

The first thing people notice is the mainplate and bridges finishing. This conversation is all about charbonnage. Then there is the open architecture, with geometric German silver bridges and 18th- and 19th-century construction – inspired by Breguet, of course. The overall look is grey, with a hint of yellow – the colour typical of German silver – and decorated with charbonnage. Now we have this nice scratch finish that we’ve added to this look.

While charbonnage is an easy identifier, I would say the open dial and probably the typical case shape, that is particular to us, are key to the French aesthetic we champion – the French style, influenced by techniques from the 18th century, and lacking in industrial design. So this is why you have a very flat central mainplate with bridges on both sides – they couldn’t machine very complex mainplates. They preferred at the time to make flat ones with big holes and bridges on both sides. It was these technical constraints that gave birth to the French style.

This is noticeable even at Only Watch [2024] for which we made this calibre with Petermann Bédat. While the calibre itself was not our own – it had the design of a classic Swiss watch – the way it was finished was typical of our style and immediately [showed] that we worked on this watch.

In addition to the Théo Auffret brand, you have also set up SpaceOne. Tell us a bit about that part of the business.

I started SpaceOne a year or so ago, while also doing a few side projects creating pièces uniques. SpaceOne has given me the opportunity to have fun and make hundreds of watches, be really creative and make some futuristic stuff, inspired by rockets and such. It also helps me keep Théo Auffret small and niche, and true to the original vision I had for this company.

SpaceOne started with a jumping hour watch and we sold around 600 of these. Then you’ve got the Tellurium, which we created with my friend and designer Olivier Gamiette, and we have sold a few hundred of this already. We made a total of €1.7m in one year. The SpaceOne company is now already bigger than Auffret. It doubled the amount of money I was able to put into developing the workshop. I also have been able to hire watchmakers who are dedicated to SpaceOne. So, it’s now a two-stage rocket.

Now we are picking up a little bit more of speed, we have developed the new calibres for the next generation of three-hand watches for Théo Auffret and we’re thinking about retail and setting up the workshop in Paris.

The Tourbillon à Paris ‘00’ isn’t just the first watch Auffret made in his own name. It is the piece with which he won the F. P. Journe Young Talent Competition. Later, he would go on to sell the finished piece as the very first of his 15 tourbillon watches.

Your story has similarities with that of British watchmaker Roger W. Smith and you have in the past talked about how his tutorial videos on YouTube have been educational. Do you feel a kinship with him?

I always found Roger Smith’s work very interesting. I have met him a few times in Dubai and had discussions with him. The last time we had a drink together, I explained to him my strategy, my ideas and philosophy on watchmaking. I think he brought something really interesting to the wristwatch space especially if you consider that George Daniels’ legacy is primarily in pocket watches and his style is not entirely British because he was inspired by Breguet. It was Roger who, in my view, took some details from George Daniels’ work and used these to create a more distinctly British style. Now when you see Roger W. Smith watches, you immediately understand that these watches are made in Great Britain. In my conversations with Roger, I explained to him that I’m trying to do what he did, [but] in the French watchmaking context.

I think the size of his operation too is attractive. I’m really interested in trying to create something similar. A really well-trained team of 10 watchmakers would be a dream.

“I always found Roger Smith’s work very interesting. It was Roger who, in my view, took some details from George Daniels’ work and used these to create a more distinctly British style. Now when you see Roger W. Smith watches, you immediately understand that these watches are made in Great Britain. I’m trying to do what he did, [but] in the French watchmaking context.”

Two examples of Chronometre à Paris, one by master watchmaker Jean-Baptiste Viot and the other by his apprentice, Auffret. Interestingly, Auffret created the original version of his prototype in Viot’s workshop.

Your new watches, the Chronometre, will eschew the tourbillon. What is the thinking behind this?

If I continue to make two to three tourbillons a year, selling them for €100,000, it won’t allow me to develop the company. One of the options available was to double the price of the Tourbillon á Paris or decrease the quality. Neither of these were acceptable.

Instead, the option that seemed sensible was to keep the price, quality and aesthetic consistent and create a three-hand watch, classic chronomètre-style.

The watches will keep the very French philosophy from the 18th century. They will be made in classic 36 and 38mm sizes, and a 40mm for the sporty watch. While we initially thought to design an entirely new case, collectors who had loved the Tourbillon à Paris encouraged us to retain the case and its details. So what we have created feels like the logical next chapter of the Tourbillon [à Paris]. We also added a little touch of Jean-Baptiste in the watch because we love what he did, and I think it’s a bit of our legacy.

The numbering will follow the style employed by Breguet. For instance, since a number #2 watch has already been delivered, there won’t be another #2 Théo Auffret watch again, even in future series.

What does Théo Auffret do when he is not at the bench or managing his growing atelier?

I’m really passionate about collecting old clocks and watches, especially school clocks that I like to restore. I also collect some old Pateks, pre-1940. I’m not a watch collector, but I’m in love with the Patek quality from this era. I almost never wear watches because I don’t like to have heavy stuff on the wrist. I have a Patek 96 with a F. B. Borgel stainless-steel case. I have two rectangular case ref. 425 – one in platinum and one in gold. I love them and they’re not really expensive – I get them at auction and restore them myself.

I’m also passionate about planes but don’t have the time to get my pilot’s licence at the moment. I hope this summer I’ll have some time for this. I also just started the full restoration of an old Porsche 911 – a 2.2 litre from 1971 – so this is going to take up a huge amount of my time now as well.