Winding back the clocks: The Watch World’s Obsession with Re-Issues

It's hard to ignore the number of watches on the market today that look exactly like ones that were on shelves four decades ago. This seems to be case across the entire industry. From the high-end, established brands to the more accessible timepieces, the desire to create watches with distinctively vintage cues is evident.

Of course, it’s not just the watch world that has seen this shift towards rediscovering old designs. Fashion, gaming and even films seem to be reaching into the archives to bring a new life to what was once forgotten. We thought it worthwhile to take a closer look at some of the re-issued models in the watch world, while also exploring why they have become so prevalent. At its very core, this topic could almost be considered an existential one for the industry. Are the best days of horological design behind us?

The clear similarities and start differences of the Chronomaster Revival.

Take Longines’ Military Marine Nationale. It offers no complication, not even a date window. It’s plain and unadorned, bar the dial, which has the speckled yellow coloration of something which has aged over several decades. Although made in 2020, superficially it’s an almost exact replica of a watch made in 1947, right down – as some complained – to the 30m depth rating, shallow by today’s standards. Winding back the clock seems to have taken on a whole new meaning.

“[These kinds of historical] models are meeting a growing success and we think it’s a sign that, for many people, and especially for younger ones, watchmaking and tradition cannot be set apart,” reckons Matthias Breschan, President of Longines. Over recent years, the brand has committed to bringing back watches from the archives, with what appears to be an enthusiastic reception from first time customers and established vintaged collectors alike. “With a model [like this one] on your wrist, you are not only wearing a watch – you’re part of the history. You have a story to tell and today an increasing number of people are looking for authenticity.”

Longines’ modern take on a War time watch.

Or, at least, authenticity of a certain kind, since arguably a replica is the definition of the inauthentic, the faux, the fanciful. Breschan is certainly not alone in arguing that his watches aren’t replicas per se, since the mechanisms, materials, sizing and detailing are modern. Yet ‘Heritage’ has become a dominant category in watchmaking over the last decade or more.

This year, for example, Breitling launched its Navitimer Re-Edition, with the model even employing plexiglass and a hand-wound movement. Seiko also introduced its SLA003, a copy of the watch worn by Martin Sheen in ‘Apocalypse Now’. Tissot premiered its Heritage 1973, a re-issue of a watch, yes, from 1973. There were also the Bulova 1970 Computron and the Zenith El Primero A384 Revival. As for Tudor, their Black Bay P01 was, in some sense, the ultimate look backwards, since the original watch was an unreleased prototype. The names of these watches say it all: “Re-Edition”, “Heritage”, “Revival”.

In part, this is a matter of "if you’ve got in, flaunt it". Many brands gain credibility with time – history adds substance, provides context and a talking point (for some consumers at least; others want the cutting-edge, the more obviously progressive). So re-issues talk up your history.

The Revival line up from Zenith.

“Heritage is something you can’t buy if you don’t have it,” notes Romain Marietta, Zenith’s product development and - here’s that word again - heritage director. “To build the future, you have to respect your past and highlight it. The idea is not to repeat the past, but to refresh it. And while the world of watchmaking mostly revolves around novelty, it doesn’t mean there aren’t good ideas coming from the past too.”

It’s a notion that’s certainly not limited to the watch world either. If ‘retro’ typically tends towards a slightly off, artificial version of a past product, the idea of replicating or reworking yesteryear is prevalent in almost every artistic and design discipline. The exception is perhaps art itself, which still predicates its value in originality, in the one-of-a-kind.

“We live in a very fast-moving world where digital technology and fashion changes all the time. Perhaps, in many instances, we’ve lost the personal connection to the things we consume and wear. That’s why ‘retro’ designs maybe speak to us a little more,” suggests Raynald Aeschlimann, CEO of Omega. He echoes the idea that retro is a braking mechanism on what Douglas Coupland calls an accelerated culture.

Breitling's approach to channelling its heritage into a modern piece.

Whereas we once revolted by generating the innovative or challenging – the stuff of the future – we now revolt by turning to the past. In this, we’re helped by the media’s constant re-runs of the past too, making it alive and accessible today. The 60s, for instance, are as prevalent today as they were, well, in the 60s. No wonder it all feels proximate and familiar.

The music industry offers ‘anniversary’ editions of past albums, while Hollywood is, in the view of many critics, blighted by the commercially sound but creatively dead-end idea of the remake. Disney’s programme of re-working its animations as live action films is just the latest instance of this. Some of the greatest hits of the car industry over the last 20 or so years have been the re-imaginings of some of its older greatest hits – from VW’s new Beetle to Fiat’s 500 and Ford’s Mk III Mustang. Even fragrances are re-released.

An unusual design that made some waves when it was re-introduced.

In fashion, which endlessly recycles the past, there’s now a distinct market for replicas of vintage pieces, with menswear brands from Levi’s to Pringle, Fred Perry to Sergio Tacchini, dipping into their archives. The likes of Real McCoy and Bronson are also producing insanely precise, stitch-for-stitch reproductions of old military and workwear garments. Why? It’s argued that getting hold of the originals is increasingly hard, both despite and because of the strong market for vintage goods that has developed.

Is that what is driving the parallel market for ‘heritage’ watches? Certainly, finding vintage originals in good working condition is increasingly hard – Zenith estimates that only 10-15% of its watches from the '60s are still in good wearable condition. Their rarity can also make them increasingly expensive. There’s also a self-reinforcing circular effect here too. “Revival models open new possibilities for new consumers, but they also legitimise the vintage models,” Marietta explains. “I think this is something very interesting about revival models: you can buy a brand-new watch with the look of something way older.”

Up close with a Zenith El Primero reference A386 from the 1970s.

And then there are trends. Lionel Favre, product design director for Jaeger-LeCoultre, adds that a vintage look has found itself in the ascendant recently. This is in part because its defining characteristics – functionality, simplicity, legibility, elegance – set it at odds with the demand for the bigger, and sometimes outlandish, watch designs that dominated the 2000s and 2010s. “Some of the designs then were sometimes maybe a bit too much. So, in reaction now, there’s a return to a more refined design, to smaller diameters, which perhaps explains the interest for this vintage spirit,” he argues.

Yet, given the prevalence of designs lifted from the archives, is it fair to suggest that creatives – or, more fairly, the accountants behind them – are getting lazy? Unsurprisingly, people in the watch world counter this notion. Vivian Stauffer, CEO of Hamilton, whose PSR and Khaki Pilot series watches hark back to designs of the 1970s, argues that it takes talent to create something that is entirely new while still keeping its original essence. As he puts it, “that’s not a trend, that’s innovation at its finest. Finding the right way to re-issue archive watches can potentially be even more difficult than starting from scratch. A blank slate offers unlimited ideas and changes, while a heritage design must be a careful balance of old and new.”

Designed for combat and now made to modern standards.

“When you raid the archives, as a creator, you endorse the idea that your role is to express the brand more than yourself. So, digging into the archives is a must,” adds Jean-Christophe Sabatier, the chief product officer for Ulysses Nardin, who admits to spending a lot of time visiting the company museum for inspiration. “But what is difficult in a creative process is not to find ideas. It's to find the right ones. The right ideas are the ideas serving a purpose, that bring some meaningfulness in terms of content.”

Then there is the challenge of bringing them to life. Much as a clothing company like Real McCoy goes to obsessive lengths to get its repro garments just right – down to recreating long redundant period weaving techniques to give a fabric a certain handle – it would also be easy to underplay the complexity of the processes involved in getting a watch re-issue just so.

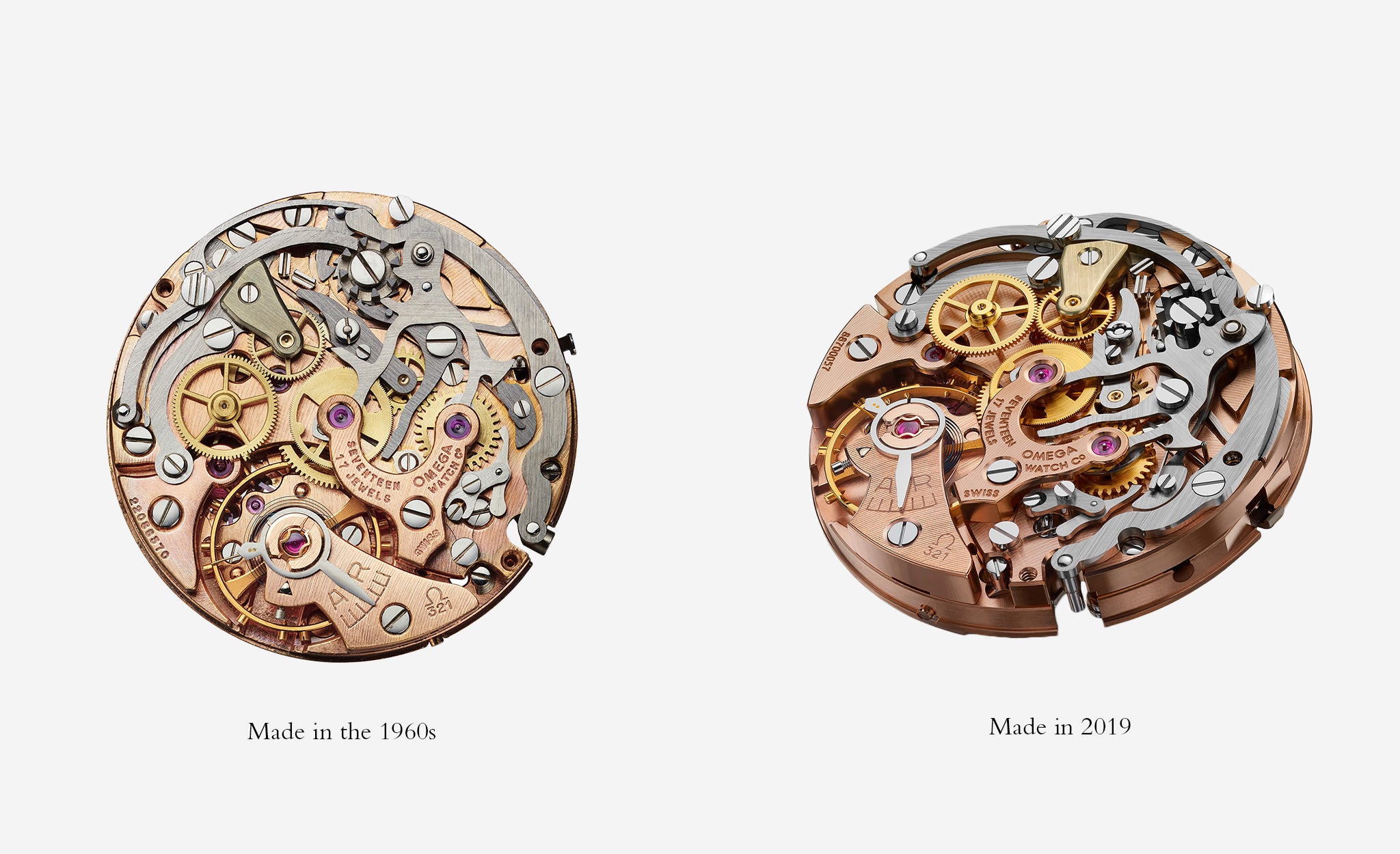

Take Omega’s Calibre 321, for example. Something of a holy grail among collectors, this is the movement which accompanied the Apollo moon mission astronauts into space. While reproducing the aesthetic of these watches may be one thing, recreating the movement, as Omega did last year, is a giant leap for heritage kind.

An exacting reproduction that captured the imagination of many collectors.

“[Doing so] took us two years of intensive research, development and trial,” says Aeschlimann. “We even employed a digital scanning method called ‘tomography’ to see inside the actual Speedmaster worn by astronaut Gene Cernan on the moon. Everything we did during those two years was about getting the Calibre 321 recreated to its absolute authentic specifications. Trust me, there’s nothing lazy about these projects.”

Perhaps, rather, the onus to explain the choice lies with us consumers. “After all, it’s the market that decides,” notes a business-minded Michael Benavente, managing director of Bulova, which has pushed its own Archive series over the last few years. “Sure, some brands have more legitimacy to take this approach than other brands. But watch companies wouldn’t be making these heritage products if there wasn’t a demand for them”.

Reaching into the archive is not just for the luxury brands in the watch industry.

Here, the argument is less that we’re searching for something authentic, as something reassuring. Reassuring because a heritage piece suggests that it is among the sine qua non of watch designs. Our heritage choices become symbolic of going to the root source of a now established custom, way or product, regardless of whether we were around at the time of the original. This is the very crux of ‘old-school’. It’s why vinyl remains the choice for many over ‘sterile’ streaming and why old arcade games still appeal too.

“Let’s be honest, this industry makes products that are obsolete, so I think all mechanical watches are in some way part of that longing for things that feel like they are here to stay,” says Rolf Studer, co-CEO of Oris, which joined the re-issue fray with its Big Crown and Diver 65 models. “It’s why people surround themselves with things that represent the very opposite of the digital world. Of course, just because something is old or looks old doesn’t make it good. What makes it good is how effectively it makes it easier for someone to tap into that feeling of security.”

“Deep down there’s something in a heritage watch that appeals to better days, even if those days weren’t really better,” agrees Benavente. “Sure, the designs are often fantastic, and it’s great to be able to introduce them to a younger generation – and that’s good business. But there’s also something very comforting about them, and in times like we’ve had this year, perhaps now more than ever.”