While our desire to travel has existed since the beginning of time, the way we travel has evolved. These vintage travel clocks are the very epitome of modern luxury, representing a way of life that is quickly disappearing, and their meaning and function is having to be redefined by today’s collectors.

Travel clocks originate from a time when vacations during summer stretched over several months; when taking a long sleeper-train would be the best way to travel internationally. Propping one of these up on your cabin’s bedside table as you cross borders in a Pullman carriage became a romanticised view of travelling that was only afforded to the upper class. However, as our ability to travel the world became easier with air travel these quickly became useless curiosities that represented a bygone era, rather than the practical tools they once were. where you would place your clock beside you so you could check the time with ease.

Despite representing an interesting period in history, these travel clocks are rarely mentioned when horology is discussed. Put simply, they were extremely practical devices that accompanied travellers on vacations, migrations, and more – and their stylishness was simply an added bonus. Here, we dive into questions such as what timepieces count as travel clocks, the different variations and styles that occur across these clocks, and of course, why we love them.

Defining the Travel Clock

First, it will be helpful to define what a travel clock actually is. Unsurprisingly, a travel clock is a timepiece purpose-built for travel. However, the size and shape of these clocks vary from larger carriage clocks with handles used by armies to smaller travel clocks used for more leisurely travel. Additionally, we have included even smaller clocks, such as purse or bag clocks, which are also travel clocks to some extent as they are designed to be portable.

These travel clocks came in a diversity of sizes, although crucially, they were all portable.

We should also define the term “travel”, which can mean many different things. At first, these clocks were created out of necessity, in the same way that carriage clocks were invented by Abraham-Louis Breguet for Napoleon to bring with him on his campaigns. Later on, more institutionalised travel (which was also seen as “recreational”) became more commonplace, such as the European “Grand Tour” that young aristocratic men embarked upon as part of their classical education. This, in turn, was slowly phased out as methods of travel became increasingly accessible to the public in the early 1900s – and the rest is history.

Intriguingly, while the travel clock design that we are most familiar with is usually associated with the Jaeger-LeCoultre Ados, this design actually appears to have originated in the United Kingdom, created by Cyril James Gowland, who filed the patent in 1932. Whether or not Jaeger-LeCoultre paid for the rights to use this patent is unclear, as few documents from this period survive in the manufacturer’s archives, but the resemblance is uncanny.

The patent filed by Cyril James Gowland demonstrating the folding case of the clock.

As we can see from the patent, the sliding leather case that transforms into a stand is a recurring theme that was widely used across retailers and watchmakers. This is most likely because of its ease of use and handling, in addition to the fact that the stand doubles up as a protective case for the glass and dial.

Additionally, according to the Jaeger-LeCoultre archives, the Ados clocks came in a variety of models, including the Ados Mignonnette, the Ados Baby, the Ados (Baby) Barometer, the Ados Chronograph, the Ados Standard and the Ados Standard Barometer, with the Standard models available with or without alarm function. Further to this, there were also the Indos clocks, which were “semi-open” clocks which made use of a completely different sliding mechanism. Rather intriguingly, when the Ados and Indos clocks were introduced to the US public, they were referred to as ‘Little Slam’ and ‘Grand Slam’ respectively.

Function and Form

With its sturdy shape and straightforward method of operation, it’s easy to see how many of these travel clocks are an excellent marriage of function and timeless design. With a clearly legible dial and luminous painted numerals, these clocks were intended to be easily readable even at night, with many also possessing an alarm function, which gave their owners another reason to take it with them. They were also very easily serviced and could be repaired easily by competent watchmakers. Above all, they were sturdy and extremely dependable.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre movements that powered these clocks are also worthy of our attention, given their sturdiness and widespread use. According to the Jaeger-LeCoultre archives: “Both Ados and Indos travel clocks were equipped with calibres made in the Manufacture in the Vallée de Joux, as soon as 1931 when the models were launched. The calibres used are: 204, 205, 206, 207, 211, 219, 438, ranging from the simple time-only movement to the more complex alarm and calendar versions.

The large, lume-filled hands and indexes of this travel clock make it a perfect companion for jet-lagged travellers.

Similar travel clocks equipped with the same movements can be found with other brand names on the dials. However, these timepieces were commissioned by these brands to Jaeger-LeCoultre and were thus entirely produced in Le Sentier, before being sold to said brands for them to sell to final clients. This is the case with brands such as Asprey and Gübelin, for example, where only their name appears on the dial and not that of Jaeger-LeCoultre.”

Behind their simple appearance, however, is a myriad of different parts and craftsmen necessary to create the clock in the first place. In addition to the clock itself, its metal case must be made, and after that, the clock must be encased in leather, taking into account the case and swinging mechanism.

According to the Jaeger-LeCoultre archives, “As of the mid 1920s, the Manufacture started reorganising its facilities so that it could internalise most of the production of its watches and clocks and be able to produce complete timepieces internally (escapements, balance wheels, dials, cases, etc.).

Not all of these clocks were cased in leather or followed the traditional folding case style – some have metal cases, while others had a “rolling” mechanism.

This required new workshops and new equipment but would allow the Manufacture to control almost every aspect of production and reduce its dependency on external suppliers. In that context, it also set up a leather workshop in the early 1930s to handle the finishing of the travel clock cases. However, by the 1940s, leather work was externalised.”

The effort and time required to produce this piece speaks to a level of craft that would have been expected in luxury items of the time. Very few modern craftsmen have the knowledge to repair or recreate such a timepiece, making the travel clock truly a thing of the past.

This is perhaps in keeping with their image as objects designed for slow, relaxed travel. Sleeper trains were a common mode of travel, and between the 1950s and 1960s air travel was still an event you dressed up for. Both forms of travel took significantly longer than they do now, requiring more than a few stops and costing quite a bit more, so these travel clocks are a symbol of a luxurious lifestyle.

Variations in Design

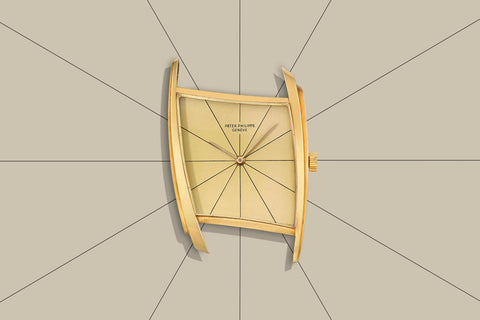

One thing that we have observed across our experience with handling many of these vintage travel clocks is the sheer variation that can be found across their dials. The clocks are also encased in many different types and colours of leather and come in various sizes.

In terms of the cases, both Ados and Indos clocks came in a wide variety of finishes. According to the Jaeger-LeCoultre archives, these also included the following: “steel, silver, gilded, chromed or lacquered metal, and mostly a variety of leather types (pigskin, calf, lizard, crocodile, suede upon request, etc.).”

Most strikingly, the design of these clocks are very similar to the Reverso’s aesthetics. The Jaeger-LeCoultre archives have revealed that “Both pieces appear in the same catalogue in 1931, and were created at the same time. Another common trait between the two pieces is that both feature an ingenious system to protect their dial: while the Reverso has a swivelling case, that of the Ados and Indos is foldable, so as to make them the perfect travel timepiece.” Furthermore, there are some shared characteristics that are instantly recognisable, such as the rectangular railroad track outlining the shape of the dial, straight lines combined with smooth angles, or the art-deco style indices. Additionally, the variety and style of the indices are often intriguing, demonstrating the same breadth and range as others have explored on wristwatches.

Many of these pieces also bear large, cathedral-style hands, which are filled with lume, while the numerals were usually painted with lume as well. These would, of course, have been for weary-eyed travellers to clearly see the time through the night as they tried to get some sleep on a moving train. However, baton and dauphine hands occasionally appear on certain examples as well.

Within the confines of the rectangular case, there was also ample space for a diversity of designs that would distinguish one clock from the other. Much like watches, these clocks bore a variety of dial colours, ranging from glossy salmon and linen dials to the more traditional black or silver colours.

The dials on these clocks came in varying colours and styles.

We have explored double-signing conventions and how these signatures would have been physically applied in one of our previous articles. When it comes to travel clocks, there is a significantly higher proportion of double-signed pieces, the dials bearing the maker’s signature in addition to the retailer’s. From this, we can deduce that there were a wide range of (now probably defunct) retailers that used to stock these pieces, making this an interesting historical study in and of itself.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre archives also note that these signatures were applied through a process called “tampographie”, or pad printing. Examples of double signatures include: Hermès (Paris), Gübelin (Luzern), Astrua (Turin), Eberhard (Milan), A. Schwob (Paris), L. Leroy & Co (Paris), Asprey (London), among others.

Additionally, some of these clocks also possessed complications, such as an annual calendar or day and date function, while a select few also possessed sub-dials or more complicated faces. It was not uncommon for some pieces to house more than one clock or function. In addition to dual timezone clocks, there were also “foursome” clocks, with the clock functioning as just one of the faces, alongside a barometer, hydrometer, thermometer, or calendar. These are harder to come by.

As suggested from the incredible combinations that were available during this period, we can conclude that these travel clocks enjoyed an intriguing diversity. This not only stems from the increased travel during this period, but also demonstrates how widely in use these clocks were, and with the varied available functions, which could support everyday lifestyles.

Why We Love Them

While the age for these travel clocks has passed, they still enjoy new forms of appreciation as decorative items on mantelpieces or desks in homes. Due to their age and simply because of the convenience of mobile phones, they are rarely actually used for travelling. Compared with watches, they are less well placed to be appreciated – you’re less likely to bring a travel clock out and about with you.

The air of romance that surrounds these objects is also undeniable. To many, the image that they conjure is both literal and metaphorical, as on one hand, in its past, the clock may have travelled to far flung places and seen more things than the average individual. On the other hand, the clock also feeds into more aspirational goals, embodying a lifestyle of luxury. Stripping away all the romanticism, however, leaves us with a well-made, sturdy clock, which brings a simple pleasure in and of itself, with plenty of design variation to dig into.

We spoke to Alan Davis, who has begun a small collection of these travel clocks. Davis is more usually a watch collector, and he has only very recently started to branch out into the world of travel clocks. When asked about his approach to collecting these clocks, he notes: “From what I’ve learnt in terms of collecting watches, I would look at these travel clocks in the same way I would examine a watch, asking questions such as if the lume on the hands matches the lume on the dial? Or the numbers, whether they are Luminova or applique, or if it looks like it’s been redone from a visual standpoint – I can’t unlearn that way of thinking, but I haven’t necessarily had the same thoughts of ‘Are these all original parts?’ as I would with a watch.”

It’s clear that the travel clock community has not yet reached the same depth of scholarship that they seem to have with watches, although there is a growing group of modern collectors who are developing a true passion for these small clocks, including those who continue to use the clocks for their original intended purpose.

Davis also described why these clocks are so interesting to him and what exactly he loves about them: “Of the four or five I own, I prefer the really small ones. They can fit in the tiny pocket on your jeans or, if I were wearing a suit, they could fit in my vest or waistcoat pocket. For someone like myself, who is constantly paying attention to the time in different cities, I like the idea of having a wristwatch on and having one of these travel clocks in my pocket for a different time zone.”

Our thanks to the Jaeger Le-Coultre Archives for giving us a glimpse into the history of these travel clocks, and to Alan Davis for sharing the story of his collection with us.