An introduction to Rexhep Rexhepi

Raj Aditya Chaudhuri

‘Artist’ is a cliché often attributed to creators, no matter the craft they have dedicated themselves to nor the years they have been at it. However, as Rexhep Rexhepi enters his 12th year as an independent maker, enough time has passed for us to recognise that he has gone through several artistic phases.

The near-universal adulation of the last few years often softens the focus on earlier chapters of Rexhepi’s story. These years are distinct both in terms of the visual identity he sought to present, and the uphill battle he faced finding acceptance for his vision of modern, complicated haute horlogerie. This is of course the case with many artists with original vision.

The initial exuberance and eagerness to prove himself gave way to a period of maturity and the inevitable desire for simplification – highlighting classical designs, symmetry and fine finishing. In this piece, we explore the development and evolution of Rexhepi as artist and his craft.

From Kosovo to Patek Philippe

Rexhepi was born in Kosovo in 1987. He led a simple childhood on his family homestead in the hamlet of Zhegër, living with his grandmother as his father travelled for work in Switzerland. Some of his earliest memories of the time are punctuated by his father’s visits to home, and the Tissot watch on his father’s wrist. Rexhepi would often get in trouble for attempting to open the caseback to view the mechanical movement inside – mesmerised by the spinning balance wheel and the locking and unlocking escapement.

When the Kosovan War broke out in 1998, Rexhepi and his family sought safety in Geneva. “I remember walking through the airport for the first time, amazed at the watch advertisements,” Rexhepi recalls.

It was difficult to adjust to a new culture, made harder by Rexhepi’s lack of French, watchmaking became a way for him to assimilate and find his own niche. He applied for a few internships, including one at Chopard, and his experiences furthered his determination to become a watchmaker. While his father initially objected – he had envisioned a life as a doctor or a lawyer for his son – Rexhepi’s mind was made. So, at the age of 14, he took the entrance test for an apprenticeship at one of Switzerland’s oldest watchmaking houses – Patek Philippe.

Rexhepi started at Patek Philippe after his 15th birthday, and it would be his home for the next few years. It was a foundational experience where he learnt everything from theory to lathe work and finishing techniques. Rexhepi chose Patek Philippe for the simple reason that it offered the most complete education – he had learnt that apprentices got the opportunity to work in the atelier’s various workshops over the programme’s three years.

Rexhepi was intent on making the most of the opportunity. Years later, his mentor Jean-Marc Figols, the head of apprentice watchmakers at Patek Philippe, who recruited him in 2002, looks back on Rexhepi’s time at the manufacture fondly. He says, “He was the most talented of the three apprentices in his group. Rexhep progressed more quickly through the training programme, asked questions, sought solutions, and showed a thirst for learning and knowledge. He was a hard worker, dedicated to his work.”

Rexhepi readily acknowledges the lasting impact the experience has had on his work. “If you look at my watches, I think all of them have something that I learned at Patek,” he says. “The watches there had incredibly beautiful finishing, and the people who [worked there] had a lot of knowledge. I learned all the basics there.”

A souvenir from those days, Rexhepi’s school watch has become a part of his mythos. A traditional pocket watch, with a lepine calibre engraved with “Patek Philippe Pièce Ecole”, it was completed as a part of his graduation requirements. Rexhepi says, “We worked on the pocket watch over three years. We did the decoration and assembling in parts until the end of the apprenticeship, and we had to finalise it before we finished our training.”

“He was the most talented of the three apprentices in his group. Rexhep progressed more quickly through the training programme, asked questions, sought solutions, and showed a thirst for learning and knowledge. He was a hard worker, dedicated to his work.”

Jean-Marc Figols

Rexhepi was also one of a small group of students who had the opportunity to inscribe his name on the dial of the pocket watch, instead of the traditional Patek Philippe signature. Figols explains, “The Patek Philippe school watch, from 1989 until 2009, always bore the name of the apprentice who made it on the dial, with around 30 watches produced. Then, from 2009 until today, instead of the [apprentice’s] name, it bears the inscription “Patek Philippe Pièce Ecole” on the dial.”

Seeing Rexhep Rexhepi on the dial for the very first time undoubtedly further fuelled his desire to one day produce under his own name. However, he prudently recognised the need for further education before he could realise this dream.

Walking before running

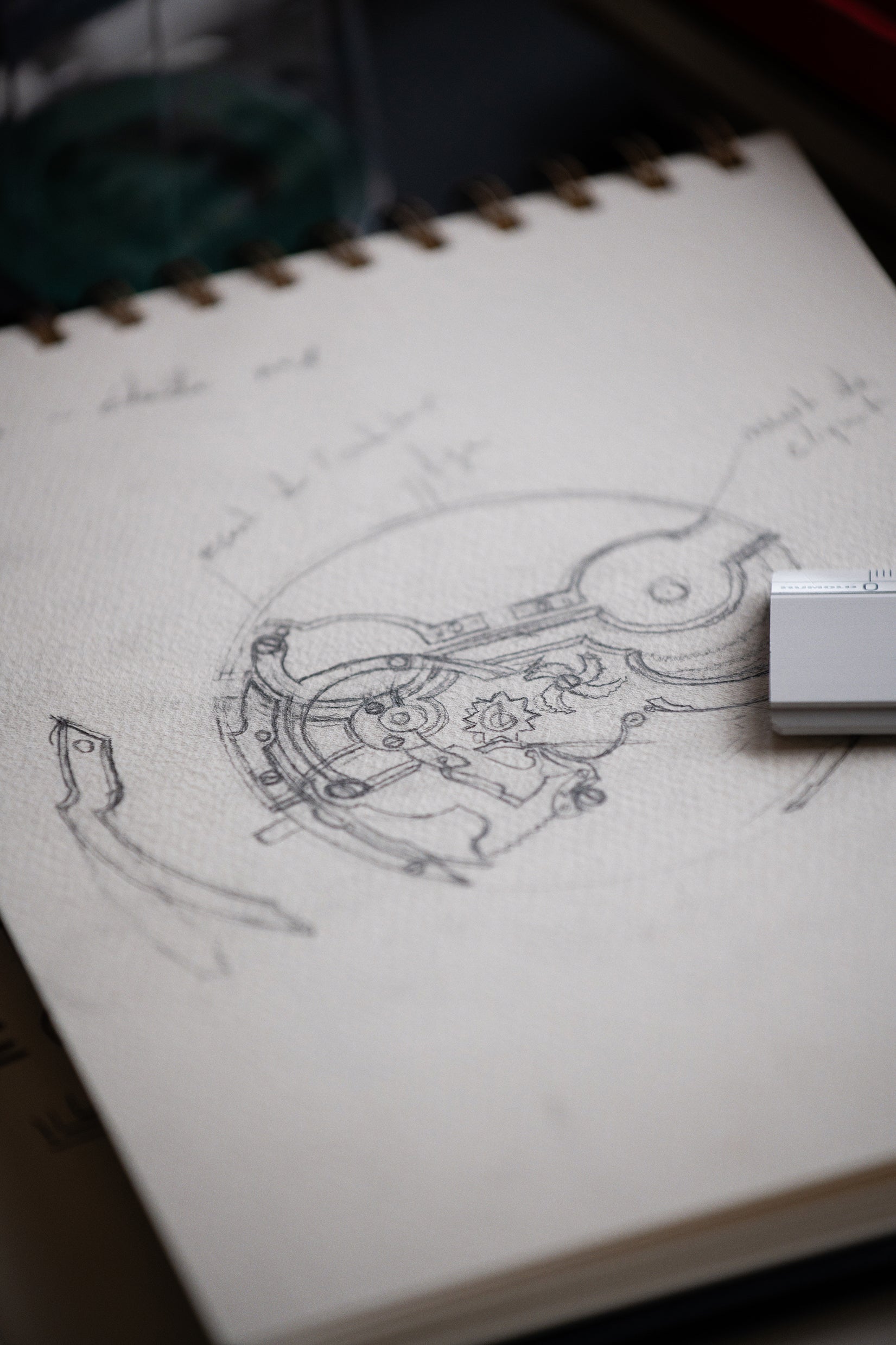

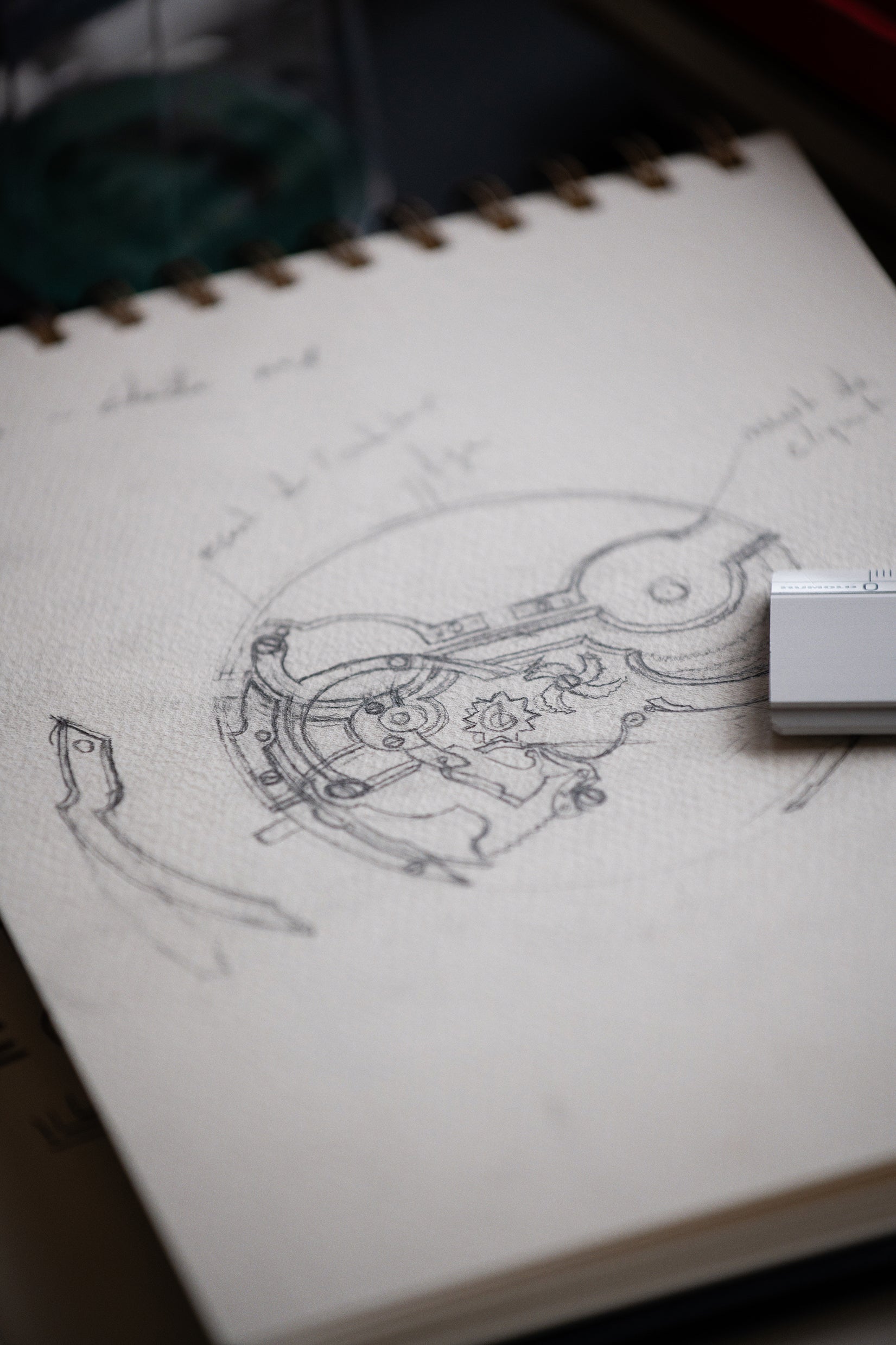

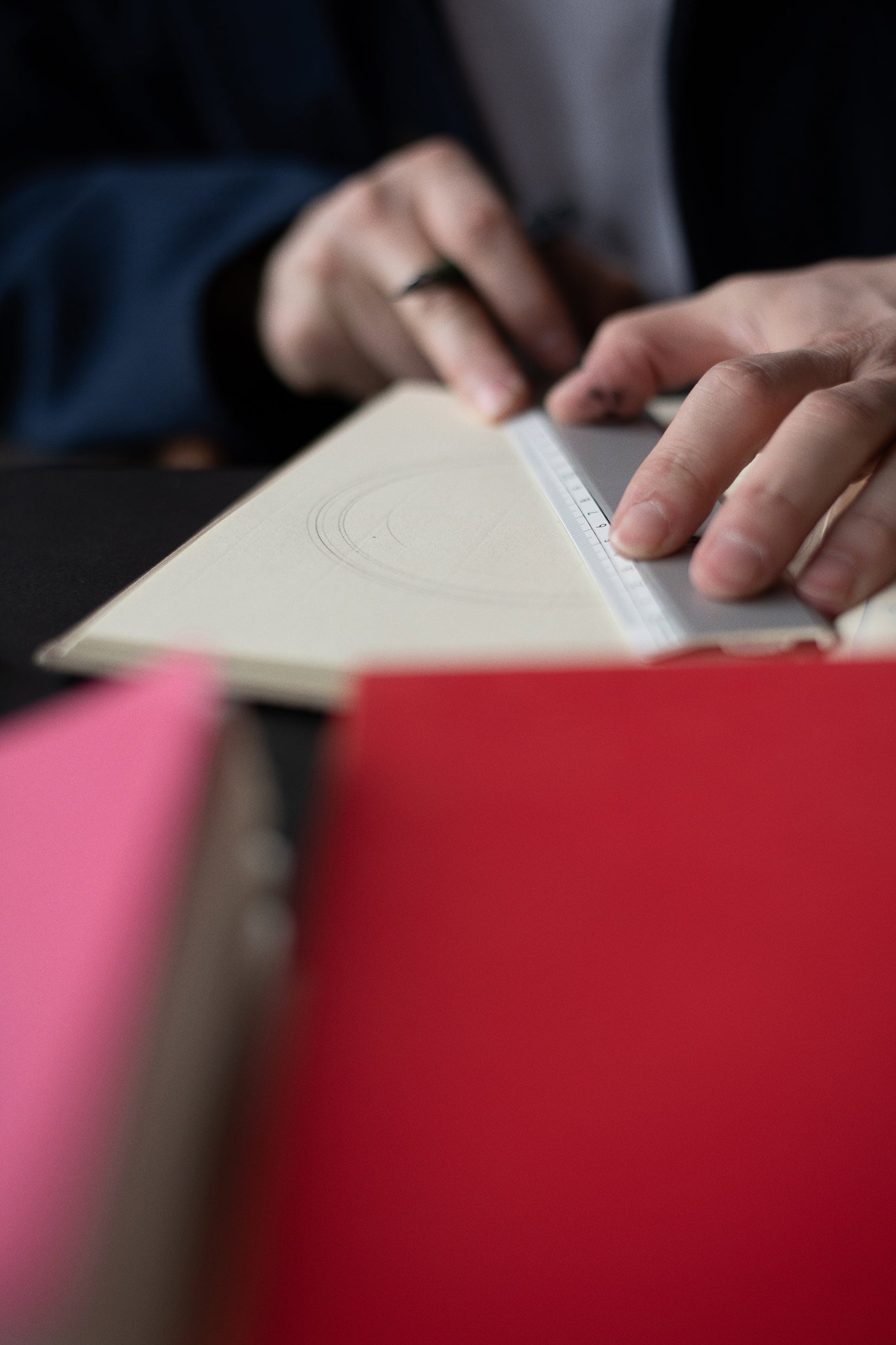

Rexhepi has eked himself out a sanctuary perched on the top floor of the historic building that houses his busy atelier in Geneva's old town. Here he works mostly solitarily, drawing and sketching in the pursuit of horological innovation.

Rexhepi’s first watchmaking job after his apprenticeship was at BNB Concept, a workshop developing complicated ébauche calibres for a host of brands, helmed by Mathias Buttet, Michel Navas and Enrico Barbasini. The latter two would eventually go on to found La Fabrique du Temps, crossing paths with Rexhepi again later in his career.

His three years at BNB Concept were focused on producing highly complicated ébauches including chronographs and several types of tourbillons for a host of brands. It furthered his appreciation for the tourbillon, which explains why the regulating device features so prominently in his early work.

Franc Vila, an independent watchmaker who worked closely with Rexhepi in those years, remembers that by then Rexhepi was already becoming adept at navigating the manufacture’s complex calibres. “My brand was one of BNB Concept’s very first clients, and we were one of the first, along with Hublot, to source the tourbillon chronograph calibre designed to be viewed from the dial side, so you can see the heart of the movement,” says Vila. He remembers Rexhepi coming over to his workshop to troubleshoot issues with the movement. “He already knew the calibre very well and he was solving any problems we faced very quickly. Once he had had a go on the tourbillon chrono movement, we never ever had an issue with it again.”

Within a year of joining the company, Rexhepi was in charge of managing a team of almost 15 watchmakers. “They gave me some responsibility, which was interesting because you can teach people. It also helps you see the workshop differently,” Rexhepi says.

When BNB Concept wound down operations, Rexhepi began interviewing with F. P. Journe, the best known and established independent brand at the time. Rexhepi says, “It was a dream for me to go and work for François-Paul Journe because he was one of the watchmakers that I respected the most. I called them, sent in my CV and did some tests and finally they engaged me. There was some negotiation about salary. After a day and a half spent completing the task I had been given as part of my interview process, I was beginning to gather my tools to leave the workshop ... I was ready to walk away. That’s when Mr Journe himself came. It was the first time I met him in person. He said, ‘Accept this [salary] for three months and we will see after that.’ We shook hands and this is how I started my time at his workshop.”

Rexhepi looks fondly upon his time there, recalling how exacting Journe was. “He was the boss, and he was the only one working on his ideas,” he says. “We had to work like he wanted us to and nobody else had a say in it. This is how things worked there. It was quite interesting because if you encountered a problem or had a question, you had to call him and explain the situation to him, and he would decide on how to proceed.” Rexhepi respected his unshakeable dedication to his vision of watchmaking.

It was a fruitful relationship, with Journe, too, appreciative of the young watchmaker’s skill. Vila, who counts Journe as a close friend, remembers running into Rexhepi again on a visit to the workshop. He says, “I didn’t know he [Rexhepi] had started working there and I saw him in the atelier de Résonance – he was working on the Résonance at the time."

"He was a very good watchmaker and François-Paul pointed him out saying,

‘He is a very good one – if not the best, then definitely one of the very best.’”

- Franc Vila

Aside from the core watchmaking competencies, Rexhepi got an inside view of a successful brand – experience that would prove crucial. “I stayed there for two years. I learnt how to build collections; build a brand,” he says. “All watchmakers there had the opportunity to assemble watches, which is something I have replicated in my workshop. I give my watchmakers the possibility to make the movement from A to Z ... think the aesthetics with which he [Journe] built his movements – the Résonance I remember was quite symmetric – had a distinct identity, which I really appreciated. I think I learned there that it’s very important to build your own identity.”

The dream of independence

Rexhepi at the bench, prototyping, finessing and embellishing by hand.

While t he experience at F. P. Journe was intellectually stimulating, Rexhepi still nursed the dream of becoming an independent watchmaker. “When I was working at F. P. Journe, after my official work, I used to go to another workshop to work on my own project and also [do work] for some other people to earn a little more money to build my own brand,” Rexhepi says. “I used to work every night and during the weekend. I was servicing [movements]; I was doing some prototyping for other brands. From 6.30pm till 11pm–12am, I worked every day. I needed to reach my goal to save CHF 100,000 that I thought I needed to start my own atelier.”

Annabelle Roques, Rexhepi’s partner, has witnessed Rexhepi’s story from close quarters, and recalls, “I remember when we were at school, and even after, Rexhep was always the one who couldn’t hang out with the others over the weekend. While we were all going out and socialising, he had to go to the workshop every evening, working away at his watches,” she says. “He was always different, single-minded in his dedication.”

As difficult a decision as it was, after a couple of years at F. P. Journe, Rexhepi quit to start AKRIVIA. “During my apprenticeship, from the time I was 16, I realised that I wanted to be independent and that I wanted to have my own brand. I didn’t expect to leave Journe so soon. But I had this [window of] opportunity, and I felt that I couldn’t miss it. I had to do it,” he says.

“I remember when we were at school, and even after, Rexhep was always the one who couldn’t hang out with the others over the weekend…he had to go to the workshop every evening, working away at his watches. He was always different, single-minded in his dedication.”

Annabelle Roques

It was equal parts brave and foolish, essential ingredients for entrepreneurship. Rexhep says, “It’s quite interesting because if you look at Journe and a few others such as Kari [Voutilainen], these guys [launched] their brands when they were a little older. For instance, at 40 [years old], you have a little more knowledge, and you have a better idea of what you want to do. You are a little more confident too. I think at 25, which is how old I was when I started, I had few ideas but honestly, I didn’t know how to build a collection. I was completely in my world. [I just knew that I wanted to] do my watch my way and I was sure that everybody would want it, and that was it. Unfortunately, when I launched, I started to realise that it’s a little more complex than that. You have to think about different pricing models and many different things. All this I didn’t really know.”

What’s to come?

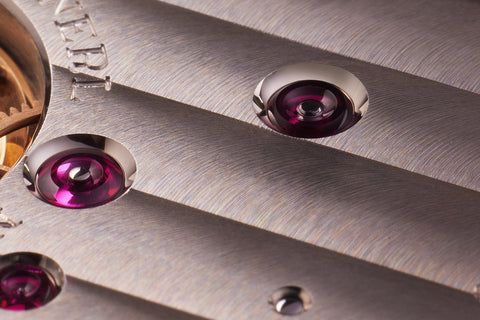

The story that started in 2013 with the Tourbillon Chronographe Monopoussoir has been shaped by many forces, chief of which has been Rexhepi’s own sensibilities as a watchmaker and his evolving aesthetic. His desire to continually differentiate himself has seen him seek new levels of finishing detail and driven him to vertically integrate his operation. From the early, mostly solitary nature of the operation, today, Rexhepi’s workshop includes a team of watchmakers, impressive micro-mechanical manufacturing capabilities set up with help from the now late Jean-Pierre Hagmann, a dial concern and even an in-house strap atelier.

We hope that by understanding where Rexhepi comes from helps appreciate the man he is and why he must create the way he does. In subsequent collectors’ guides, we will continue his story, examining the artistic phases he has gone through in the 12 years since he founded AKRIVIA. By viewing each reference not just in the context in which it was made, but with the benefit of hindsight, coloured with insight from industry veterans and Rexhepi’s contemporaries, we hope to create up-to-date tapestry of his story.

Our thanks to the following experts and collectors who have shared their time, expertise, and watches with us. This list includes Jean-Marc Figols, Philippe Dufour, Laurent Ferrier, Kari Voutilainen, Jean-Claude Biver, William Massena, Gaël Petermann, Wes Lang, Todd Levin, Firmin Li, André Gigon, Peter Wais, Theodore Diehl, Theo Danjuma, Mike Bindra and Jean-Pierre Hagmann. We would like to thank all of them for their input.

We are especially grateful to Rexhep Rexhepi, Annabelle Roques and the team at AKRIVIA for opening up the workshop and themselves to us and walking us through this remarkable journey they are currently on.