The Philosophies of Stephen Forsey

Raj Aditya Chaudhuri

Against the backdrop of recent discourse – seemingly dominated by demands for a return to a fabled past – it is refreshing to meet someone whose entire career has hinged on the premise that we can do better. After all Stephen Forsey, who co-founded Greubel Forsey with fellow watchmaker and business partner Robert Greubel, has built their brand on the stubborn refusal that mechanical watchmaking in general – and the tourbillon in particular – has had its moment.

So why then did Forsey suggest the Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle when we asked him to pick a place to meet outside of the brand’s atelier? Was he hoping to impress upon us the sense of history that has guided him and his 20-year-old brand? Or was it perhaps a place that felt like home, owing to the proximity to La Chaux-de-Fonds, where the Greubel Forsey atelier is located?

The morning we arrived at the Château des Monts – the historic 18th-century manor house that has been home to the museum since 1959 – there had been a fresh dusting of snow. The chateau’s grounds, located on a hill overlooking Le Locle and dotted with animal sculptures by Edouard-Marcel Sandoz – donated to the museum by his brother, Swiss composer, writer and collector Maurice Yves Sandoz – were wrapped in a thin white sheet of frost.

Forsey arrives a few minutes after we did. We hear him before we see him, warmly greeting the curator. He moves with an ease that suggests he is entirely at home in his surroundings and immediately assumes the role of host and guide. He gravitates towards a pendulum clock on the ground level of the museum.

ACM: Is this one of your favourite exhibits here?

SF: This long case clock by Thomas Stubbs of London, from the late 17th century, is remarkable. It’s a three-train movement – you have quarter striking, the running time – so quite a high complication for the end of the 17th century. There is a pendulum with a window – it was something of a thing at the time, to be able to see that you had a long pendulum clock, because they were really quite new. The first long pendulum clocks were from around 1670.

Think about the context these were made in – no electric light, no power, sometimes you had to make your cutting tools – very rudimentary equipment. Even the raw materials were a challenge to come by.

At the beginning of the 17th century, you had clocks with only an hour hand. This was for two reasons – clocks had gone from a bell strike to having an hour hand, because the precision was perhaps to one hour a day. Later in the 17th century, you also have a minute hand, as you start to get more precise – the pendulum immediately brought a level of precision. But an interesting detail that you don't often notice is just inside the Roman numerals, the chapter ring is divided into four, not the typical five minutes. That is a hangover from when you just had hour hands showing the quarter of the hour. Interesting, isn’t it?

For the mechanism, there were perhaps a couple of workshops that made complicated movements, but it was still in its infancy. Then you would have somebody for the dial. There would have been a caser, and he would have had craftsmen specialising in marquetry, working on this case with different fruit woods, with perhaps some ebony also in there. So, something like this would have been the work of quite a few craftsmen.

There is a line from here to the watches that bear the Greubel Forsey mark, isn’t there?

You are right. We too have specialists working on the Hand Made watches. We’re able to make two or three pieces a year in the workshop with six to eight people. It’s quite a big capacity to do that. We also have a couple of specialists who work outside the company, doing some very difficult things [for these watches]. Typically, with a handmade artisan piece, you would work individually, so you’re kind of building a prototype. What’s unique about our Hand Made [collection] is we work to a level of precision that we have in our main collection. It is quite an evolved approach.

While the first two floors feature exhibits by era and collections, the topmost floor of the museum offers a broad sweep of humankind’s efforts to record the passage of time. The most primitive – a cross-section of the Jura landscape with time displayed in different layers of soil – shares floor space with modern timekeepers, compressing tens of millions of years of development onto a single floor of the museum.

The display takes visitors on a journey from ancient, large-format clocks to the advent of marine chronometers, a tellurium (of the sort that inspired the one CompliTime made for Richard Mille) and one of the smallest pocket tourbillons ever created, made by James C. Pellaton. By placing some of the examples seen elsewhere in the museum – such as the opulent French bronzes, more austere looking clocks created in the aftermath of the Calvinist reformation in this part of the world and fine examples of Neuchâtel clocks – in such chronological context helps appreciate how one might have informed the next.

While it’s conceivable why you, like many other watchmakers, got your start in restoration, could you tell us what it was like embarking on this journey when you did?

When you are able to look back on past centuries, you get to see the work of different makers and their different mechanisms, techniques, [and] styles. You also know, particularly in terms of mechanism, what was tried and tested, what worked well and what didn’t work so well. It’s humbling, I find. We have so much technology today, all around us, and it’s still hard to do things really well.

My interest initially was in restoration because where else can you find such a mixture of mechanics and harder science within horology? I saw there was definitely an interesting career to pursue; I loved making things and machines. Perhaps it is the fault of my parents for dragging me around lots of museums and country houses in the UK to see collections that had clocks, among other things. So I suppose that filtered through and gave me that base and that passion for the culture and appreciation of the history and tradition. This helped to lay the foundations. After [that], it was a lot of hard work.

The Meccano model [that informed early tourbillons] is not anecdotic. I had my father’s Meccano that he passed to me when I was a kid, so I made stuff out of that. You start off with that and it teaches you the basics of mechanics [and] construction, and then you get into geared things. It’s quite interesting to do concept work. My son was hoping for a tractor; he got a concept model of the Double Tourbillon 30°. I'm not sure if he’s ever forgiven me.

You came to watchmaking at a difficult time. What was your initial education in the UK like?

In the early 1980s in the UK, you’d have to be mad to want to go into [watchmaking]. It was also not great in Switzerland then, but in the UK there was nothing left, really. The National College of Horology and Instrument Technology used to be in Northampton Square. Then it was moved out as the industry declined, decentralised from Clerkenwell, and moved out to Hackney once, and then a second time. I got there in the 80s and we were parked on the top floor where the rest of the building was people training for administrative work and things like that. They put us away in the attic, out of the way.

But we were fortunate because we had teachers who, although they were towards the end of their career and had perhaps lost their job or network in the [Mercer] chronometer factory in St Albans, they had their lifelong experience and the training from the time when it was much more hands-on. So we were able to pick up those skills. While the theory is great – you need that background – but it’s about hands-on experience. I think [there were 12 of us] in the class. [By the time] we finished, [there were] perhaps eight.

It was a time when we [had] a rush of technology coming, but for me the culture was always there for the antiques and it was something which is enduring and lasting, the heritage and tradition.

As we pass through rooms with impressive ornate examples of Neuchâtel clocks, Forsey reflects on how things would have been in London around the same time. “The earliest clocks were made by blacksmiths – they were forged-iron tower clocks, which are big format,” he says. “They would literally forge all the wheels and cut them out by hand. They were quite rudimentary. Amazingly, they worked for hundreds of years. From there, when the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was founded in 1631 in London, it marked a split from the Blacksmiths Company. The Worshipful Company of Clockmakers was founded by Edward East and a few other craftsmen to ensure a high level of training [and] quality. Then they became a master and then a master craftsman. Only then could you practise in the City of London.

Forsey walks us through centuries of curiosities of the Maurice Sandoz room, where nothing is as it seems. Made by masters such as James Cox, Henri Maillardet, and the Rochat brothers, they stretch in styles from Oriental to retour d’Egypt, offering a glimpse into the worldwide clientele they were made for.

Forsey is most taken with a beautiful hand mirror, its vibrant adornment with inlay and enamel work hiding complex mechanics. “At the top you have this tiny, tiny singing bird enclosed within a flower,” he says. “Normally the petals are closed. Then the petals open, and the bird sings and flaps its wings and moves its beak and tail. This is just incredible when you think that you have the mirror, that isn’t so thick and you have to get the energy from the handle, where the mechanism lives, up to the bird to operate the different functions.”His sense of history is robust. Moving from one era to another, Forsey is quick to find his bearings and share anecdotes and details that bring that period to life. Being surrounded by it at the Château des Monts perhaps causes him to reflect on his own contribution to this unbroken chain of history.

Perhaps another reason Forsey picked the Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle was because it was the scene of one of the brand’s proudest moments. The museum hosted one of the last chronometric competitions, the Concours International de Chronométrie, between 2009 and 2019. In 2011, the Double Tourbillon 30º scored an astonishing and unassailed 915 points out of the total 1,000, making it the most accurate timepiece to ever partake in these trials.

When we leave the Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle we drive on narrow, serpentine country roads cutting through the snowy landscape, avoiding the busier arterial stretch that connects Le Locle with La Chaux-de-Fonds.

The recognisable outline of the brand’s atelier is visible from a distance. Less apparent, perhaps because it is more native to the landscape, is the farmhouse adjoining it. While it appears diminutive in comparison to the modern building, the farmhouse’s interior is cavernous, framed by exposed wooden beams and sand-coloured bricks.

It is the entrance for visitors to the atelier – the only way into Greubel Forsey’s world. You have to step through 350 years of history and appreciate its textures and imperfections before getting to the polished glass-and-steel modern atelier. Forsey tells us the architect was inspired by the geological folds of the Jura mountains, creating the new atelier to appear as if birthed by the landscape.

It is also entirely appropriate that guests are hosted in the room adjoining the smoking chimney, where the families inhabiting the farm would have spent the cold winter months, huddled together, sleeping in box beds, maximising their collective bodily warmth and the heat from the chimney next door. It was also the room where any watchmaking activity would have taken place.

To the right of the atelier lies the original farmhouse that has stood for more than three centuries. It was carefully restored, often using bricks, tiles and wooden beams rescued from other similarly traditional farmhouses. The tiles on the furnace are one such detail. Looking closely reveals a motif of a farmer carrying a large format clock, something they could have created over the winter months, to a potential client.

Tell us about coming to Switzerland.

It was obviously quite a change. I came to WOSTEP in 1988 and back in 1990 for the complicated watch restoration course. I wanted to see how they made watches in Switzerland; I was interested to learn more. The opportunity came up at Renaud et Papi and the interview was with Robert [Greubel] – he was joint managing director. He couldn’t speak English, and I couldn’t really speak French, but we managed to find some kind of entente.

When I moved out here, I didn’t necessarily intend to stay; I thought maybe a year or two and then [I’d] go back to England. But, of course, there’s always a new challenge. Through the 90s there was so much to do. We started from a point that was really the very beginning of working differently at Renaud et Papi. There were a huge number of possibilities.

We were working there – six or eight of us, including Bart [Grönefeld]. They’d basically employed the full graduating class from that year in La Chaux-de-Fonds. It was the beginning – we had nothing. No special tools; hand-finishing was embryonic because it had all been left to abandon. In a sense, Renaud et Papi had restarted everything in the late 80s. Robert joined them in 1990; I joined in 1992. We had to do everything – for the machinists, you had CNC machines, but they weren’t super-precise down to the tolerances we needed to build a complicated repeater mechanism. Gradually, with each batch of parts, we were able to improve. By machining precisely, retouching less and using a more qualitative approach, we were able to improve fit and finish.

I think I met a similar vision and idea in Robert, neither of us accepting that everything had been invented. It’s when you ask the right question you can find the right answer.

So, what was the question that brought you two together?

On one side, [it was] in terms of the tourbillon, which had been widely criticised in the 90s as just being a kind of a gadget, not bringing any improvement in time-keeping performance. So that was really a strong motivator to [ask], “Is that really the end of the story for the tourbillon?” Maybe we just haven’t ever had the chance to develop it further and take it to another level. So that was obviously a strong element. Then there was that pursuit for excellence in terms of quality and reliability that we mentioned earlier – try to seek to offer complicated watches [that] had the level of reliability that [meant] you could use them on a regular basis without encountering problems.

What was your education at WOSTEP like?

At the time Antoine Simonin was the director and he was a very strong, passionate watchmaker and an excellent communicator, teacher, and collector of antique horology. He inspired us. He defended that [classical] training through the dark lands of the 80s, teaching hundreds of watchmakers from around the world over a 25-year period.

I think it gave him [Simonin] pleasure on a Monday morning … he’d take a movement [that] was working really fine, and he’d take the balance out and then he’d take the hairspring and just rub it between his fingers, so we had to make a new one. You had to get a raw spring and cut it, pin it, count it, and then do a second counting to get pretty much within a COSC [Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres] performance, although at the time there was no opportunity to actually test them.

Alongside that, because the school was private, he [Simonin] had repairs that people would bring in. So, you had the chance to work on different other repairs. You could make progress with that. We were there in the evenings, weekends, building up, and improving our bench skills.

WOSTEP gave us a chance to visit different companies. When I came in 1988, some of the visits we did were really mind-opening because they were companies in full transition. [They had] their 1930s [and] 1950s machines still, but next door to that they had CNC machine plonked there and the challenge of managing the paradox of these two worlds.

The years leading up to the new millennium were marked by concerns such as Renaud et Papi and Techniques Horlogères Appliquées, where talented young watchmakers shared bench space creating complicated calibres for established brands. Just before the turn of the century, a number of these watchmakers embarked independently. While Robert Greubel and Forsey initially sought to replicate this model, creating a company called CompliTime to make pieces for other brands, by 2004 it would morph into Greubel Forsey with the Double Tourbillon 30º as the new brand’s first innovation.

The brand has a very recognisable aesthetic. What inspired it and what are the codes that continue to guide it?

Robert had a good experience with product design already, back from his days in IWC. We didn’t have that exercise of trying to start somewhere and then finding a path. We already had so much to do that we didn’t want to have too many pots on the fire if we could avoid it.

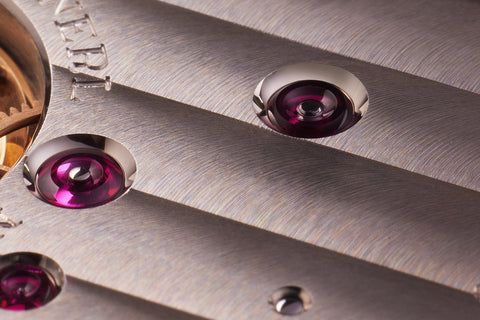

From that, we sat down and made a list of codes that we felt would be the signature of Greubel Forsey. Without taking the Coca-Cola recipe out of the safe, there are a few codes we can discuss: the pressed-in gold chatons for the jewels; hand-finished and blued screws when it’s appropriate to blue them; there [are] elements of the finishing such as the barrel polishing. Some things we revived, such as the grainage, because Côtes de Genève is great, but we’re not in Geneva.

The Nano Foudroyante EWT [Experimental Watch Technology] – it’s very sober looking. That really restrained dial construction I think reflects our characters, Robert and mine. We saw some of the exhibits in the museum that speak to a deeply seated sensibility. I am not into over-exotic things.

Both the Hand Made 2 and the Nano Foudroyante EWT represented a perceptible shift. Their classical basis speaks to a change within the organisation. There was a new, young chief executive in the form of Michel Nydegger, who formerly headed the brand’s communications and is Greubel’s stepson. Plans to expand the atelier and ramp up production, spearheaded by the former CEO Antonio Calce, were put on hold almost immediately. We spoke briefly with Nydegger during our time at the atelier.

In the weeks since we met with Forsey on that snowy morning in February, the brand has announced a clear break with Calce, the latest move in the consolidation that began with Richemont relinquishing its stake in Greubel Forsey in 2022. Greubel Forsey’s direction once again will be the sole purview of the two whose names are on the door.

The scale and capabilities of the atelier are considerable. The atelier produced about 200 pieces in 2024, a minor reduction in volume from the year before. It is but another indicator of a refocus.

Forsey says, “We’re not in the artisanal, one-of-five-pieces bracket, but we’re not on the industrial side, either. We’re kind of in a hard place in the middle where we want the best of both of these, and we want to bring it all together and to push it further. Like for Hand Made, to make these watches to a level of tolerance and execution of our other pieces in the collection. The difficulties of attaining that are just exponential and something you can’t plan for mathematically.”

It’s been more than 20 years of Greubel Forsey, so more than 20 years for you as an entrepreneur. What are your learnings and what drives you still?

If you know all the things that are going to happen en route, then you may never start. I used to describe it sometimes like climbing a mountain, except there is no summit. It’s just a succession of false flats – each time you think you’re nearly there, you realise there is still higher to go. If you think about Greubel Forsey, Robert and I had a vision to look at different mechanisms and see if we could improve them while defending, practising and preserving traditional skills. We hoped to find a unique mix and make it relevant to modern sensibilities. I guess there’s an energy, an invisible motor, driving you on.

We started with the tourbillon, which we launched as the Double Tourbillon 30°, then the Quadruple Tourbillon and the Tourbillon 24 Secondes, which gave us three engines. Once we had our three tourbillon motors, we needed to look at the escapement and the balance system, and so the [Balancier Spiral] Binôme was one route and it brought us some information, but it wasn’t the whole story.

Then we could develop our QP à Équation, the GMT Balancier Contemporain, and explore artistic angles as well, producing watches such as the Grande Sonnerie. Now with the Nano Foudroyante [EWT], we’re able to finally get to the chapter of measuring intervals of time and looking at the split of time. We are always looking at different things – we made silicon parts and we had them running in the workshop for years and years. In fact, they’re still there, but we never deployed [them because they] didn’t really fit, but we wanted to know about it. All of these are projects that bring pieces of the puzzle to enable you to go forward slowly but surely.

I think the collection demonstrates [this] very well, across that spectrum. It wasn’t the idea to be the cheapest [or] the most expensive. Cost, as Michel [Nydegger] said – and I have to confess it’s true – was rarely a consideration. When you do something for passion, you don’t cost because you can’t. Of course, for it to work, you have to arrive back at zero somewhere. However, projects such as the Double Tourbillon [30º], we worked on for four-and-a-half years. On the eve of Basel 2004, Robert and I looked at each other and we said, “Well, we’ve got the three watches, so if it goes badly, we’ve got debts to pay for five years. But we’ll have maybe a watch each. And if it goes well, we’ll carry on.”

You know, sometimes you have the courage of your conviction to keep going. With any idea, you never know if it the last one. It’s a little bit like for a writer or anybody who’s creative – you have a piece of writing that’s really fantastic and the next one is a struggle. And you just don’t know why – you can’t put your finger on it. So you’re just grateful when it works.

The Mechanical Nano, Greubel Forsey’s 10th fundamental innovation, is an umbrella term, involving the miniaturisation of components so the energy consumed to operate them is near negligible. The Nano Foudroyante EWT is but the first proof of concept. The brand can be expected to deploy such nano mechanics to a host of ends in the near future.

While the Hand Made 2 could be viewed as the other end of the spectrum, the difference between these two disparate schools of watchmaking has historically been the limitations of micromechanics. Greubel Forsey is well positioned to shrink that distance between nano mechanics and hand craft.

What was the thinking behind setting up EWT?

There was this general opinion in some quarters that tourbillons could not be more precise than standard movements. So then you need to analyse that. We had a laboratory where we looked at the performance of different mechanisms and we started searching. That brought about a working method, and that’s the essence of EWT – to look at the subject and then not necessarily just try to evolve that, but to try to brainstorm to see if there are different ways of doing something.

From that you sometimes evolve two to three concepts. For example, with the QP it was a similar thing. There were different concepts and then you realise one of them is the winner, or it’s a combination [of the qualities of different iterations] or we need to go back [to the drawing board]. [It’s] like when we first did the synthetic diamond balance wheel and spring, the [Balancier Spiral] Binôme, back in 2006. That’s an example where the technology was not there [for us] to be able to make it in series. But we learnt a lot. From that, are other spin-offs that help to lead us … towards the Mechanical Nano. There’s rarely a bad experience because you can draw something else from it.

If you look at it as a cost exercise, a purely business exercise, it doesn’t make any sense. But, like Michel said, we have had that independence to be able to make those choices.

The Hand Made watches have had a long gestation too. The offering traces its story back to the Time Æon Foundation that Greubel Forsey championed, along with watchmakers such as Vianney Halter, Philippe Dufour and later with Felix Baumgartner and Martin Frei of Urwerk. Forsey says, “It was created to preserve, safeguard, and transmit traditional skills. The Hand Made 1 in 2019 was the fruit of a long project starting way back in 2005-06 with Time Æon. We realised, along with other independent watchmakers, that there was a problem in terms of the level and quality of training for watchmakers, certainly in Switzerland, but also [around the rest of the world]. So that gave birth to the [Le Garde Temps -] Naissance d’une Montre, to try [to] gather together those skills. There were also people coming from in-house wanting to practise those skills. This led to Hand Made 1 and then Hand Made 2.”

Parting Thoughts

Forsey is many things. He is as English as he is Swiss. He is a traditionalist and also a force for bleeding-edge innovation. His preference for restrained design has not precluded him from creating some of the most avant-garde designs. As with the watches he has been putting his name to most recently with Robert Greubel, he has shown an ability to bring the two poles he lives between ever closer.

It is perhaps fitting to end with a quote from the watchmaker that goes to the heart of the man. “Looking at antique pieces, it’s kind of humbling to see what they managed to do 400 years ago, which was already pretty good even by today’s standards,” he says. “We’ve got all this technology, skills, materials and cutting tools that they never had. So, let’s get out there and get on with the job.”

We are grateful to Stephen Forsey, Michel Nydegger, Marwa Turki and the wider team at Greubel Forsey for their time. In addition, we would like to thank the curator of the Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle for opening their doors and treasures to us.

Photography by Jana Anhalt