Interview: Doo Sik Lew

By Russell Sheldrake

Doo Sik Lew can be thought of as the youngest of the old guard in watch-collecting terms. Before this current batch of new collectors-cum-speculators entered the market, Lew was already establishing himself as a byword for taste and curation, seemingly only buying well and commissioning even better. He took notice of the small independents that were starting to gain momentum long before they were thought of as smart investments.

For many years he was only known in the watch community as @doobooloo – a colourful yet mysterious moniker under which he led the way with some of the best amateur watch photography in the early days of Instagram. However, describing anything Lew does as ‘amateur’ is slightly misleading: you won’t find every collector on Instagram talking about focal stacks.

He majored in engineering at college with the dream of becoming an architect (having always been fascinated by design), but ended up in finance, where he finds himself today. We caught up with Lew for a detailed discussion about his journey in watchmaking, from picking up his first Panerai on a whim, to amassing the ‘Impossible Collection of Journe’.

ACM: Let’s start in that clichéed way, and tell me about your first watch.

DSL: I remember I was walking around town in Manhattan with my wife, and we happened to be standing on Madison Avenue right by a Panerai boutique. I’ve always been fascinated by their design. This was at the time when I really didn’t know much about anything, only because I was too afraid to start delving into the intellectual assets of things, because then I felt like I’d be sucked into it. That day I walked out with a watch on my wrist; it was a 42mm titanium Radiomir. It was really surreal, I couldn’t sleep for like a week after that event. I felt so guilty for having spent $6,000 or $7,000 on a watch and I felt like I committed a real sin, you know? But that was the beginning of the end for me.

From having first dipped his toe into watches with a Panerai, it could be said that Lew is now deeply submerged in the horological word.

So you had this engineering background from your studies, yet you say it was the design of the Panerai that first drew you in. Would you describe yourself at the time as being a movement guy or a dial guy, and do you think that has changed over time?

You know, that’s a very fundamental question that tugs at the core of this hobby for me. Continually, I have to grasp why I am doing this. And I feel like I’ve been pulled both ways; there was a period where I cared about nothing but the movement, so I became a movement snob, in other words. Not that these watches were not beautiful watches, but there was a period where I was very much a snob about finishing, mechanics, and chronometry. For a large part of it, I brushed aside the aesthetics of a watch for the mechanical aspects. I went through that phase for a few years, and then I swung back to focusing on design, and looking at watches as a sculptural element, focusing on it as art on the wrist.

I think I’m at a point now where, having been a geek on both sides, I have come to realise that this life is not so one dimensional after all. My quest now is to understand what makes a watch truly desirable. A watch can have many desirable aspects to it: the movement, an amazing dial, a finely crafted case, high complications – it could be many different things. But there are so many watches out there that do nine out of 10 things correctly, but somehow fail to be a desirable watch. What it means to be desirable to the market – to the world – and what it means to be desirable to me are very different things, too.

Having oscillated between design and mechanics over his collecting journey, Lew has come to accept that the definition of a desirable watch is just as mercurial.

Can you think of an example from your collection that illustrates that pendulum swing for you?

When I first discovered F.P. Journe, they had a boutique within walking distance of where I lived in New York. One day I walked over there, checked out a couple of watches, I think it was a boutique edition that was on display and I ended up just buying it. And that’s how I got started with the brand. Then I really learned more about it and I just started digging deeper.

Fast forward [and] I had this collection that could be compared to those coffee-table books, The Impossible Collection of Cars and what not. I mean, to me at the time, I felt like I had assembled this ‘Impossible Collection of Journe’, at least from my very childish perspective. I had about six to eight – 10, maybe a dozen – watches that I had very carefully collected over the years and travelled all over the world to acquire, and they just stopped feeling special to me at one point. It was a very strange realisation. I had this watch tray with all these special Journes, and I knew how special they were, how rare they were – many of them were unique pieces – but I just couldn’t feel it anymore, you know? I’d become so desensitised.

“A watch can have many desirable aspects to it: the movement, an amazing dial, a finely crafted case, high complications – it could be many different things […] What it means to be desirable to the market – to the world – and what it means to be desirable to me are very different things, too.”

So I said, look, I’m going to sell it, because at the time everything felt like you could sell them and buy them down the line, probably cheaper, so I was going to sell everything and move on, [then] come back after spending a year or two in sabbatical and see if I still have love for the brand. So that was an interesting moment – I think that ties into the discussion of swinging the pendulum back and forth.

When you were building this ‘Impossible Collection of Journe’, was there a philosophy that you were trying to follow?

I think I was in this mad dash at the time. When I was collecting them I just wanted to try everything; [I had] this burning curiosity [to find out what it meant] to collect rare things. It’s not like collecting things was something that was ingrained in me or my family, or something that I’ve seen growing up, so [I wanted to know what it meant] to buy these things.

Once a focused collector of Journe, Lew has since refined his collecting ethos.

I guess I really wanted to be – and there was a little bit of a vanity element – perceived as somebody that collects a lot of cool Journes and carve out a niche for myself. I can’t do that with Patek Philippes, for example – that would require way more resources than I could ever afford. Journe, at the time, was still very much a niche brand [and] maybe a handful of people really played in collecting Journes at a serious level. So there was a little bit of that vanity factor, I must admit. Looking back, it’s funny, but I guess that was a real driving factor: I wanted to be seen as that Journe guy. Which is, once again, kind of interesting because now we have our mutual good friend, the resident expert who is called The Journe Guy, who actually is the Journe guy [both laugh].

Are you able to pinpoint any milestone watches in your collection over the years – pieces that stand out to you and have taught you something?

I think the Observatoire is a milestone because when Silas [Walton] first started WATCH XCHANGE, that watch was one of the first watches on the website. And I remember one of the preconditions of buying that watch was asking Silas to connect me with Kari [Voutilainen], and so he did. So I bought the watch, and Kari was in New York a couple of months later and he had graciously lent me some of his time, and we had lunch. This led to me ordering my first custom watch. I had this historically important Observatoire in my hand and wanted to make a sister watch that essentially mirrors it. I proposed this to Kari after our meeting and he graciously accepted to do this one-off from his Vingt-8 series.

A Chronometré 27 made by Voutilainen, based off an observatory-grade Longines 360 ebauché.

At first I said, in terms of a colour scheme, since the original watch had a gold case, white dial and greyed hands, why don’t we mix it up a bit and let’s do a white case, grey dial and gold hands? So we’re carrying over the same elements, just mixing it up a little bit, and I thought that was fantastic and the result was really wonderful. And then I did something interesting; I got really greedy with my desire to design my own watch. I asked Kari [if he was] able to do another set of dials for both the Observatoire and the Vingt-8. I ended up working with him to come up with a kind of Darth Vader-type of a look on my Vingt-8, where it was a completely blacked out, full-gloss, lacquered dial with black print, with blacked-out hands in a steel case. I wanted the Observatoire to have the opposite – the same thing but just a white theme. It was fun for 15 minutes when I first received it, and then I realised I had robbed Kari of all his visual identity. I was left asking myself, what was this watch? It was not my watch, nor Kari’s watch. What is it?

This became a very informative and educational moment in realising what customisation is, and how one does it tastefully. But more [importantly], how does one do it [and show respect] to the creator? As soon as a watch becomes a custom creation where the spirit of the customiser starts to outweigh the spirit of the creator, then I would say the project has failed.

It certainly seems like customisation in the watch industry has come a long way in the past few years. What else is really exciting in watches today?

I think the answer is two-fold: seeing what these younger guys can come up with, and in turn how these younger innovators will encourage or force some of the larger brands to react. We can all make the argument that there’s been a sense of complacency in the industry for some time, but I think we can certainly expect to see that change positively going forward.

Lew at the 2021 GPHG ceremony where he was a jury member on the panel, presenting an award.

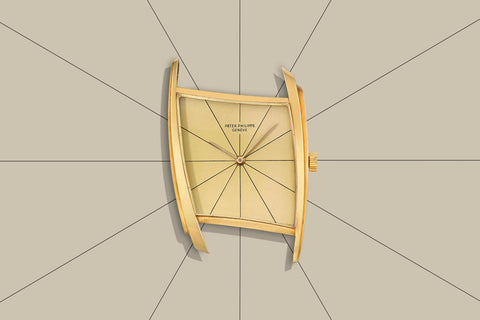

Personally, I’m at a stage where I’m finally starting to discover vintage – even newer vintage, like the 1990s stuff, which I’ve always been fascinated with. But once again this goes back to my point earlier – if you’re stupid, you’re brave. You know everything, but you don’t, and I’m just finding that there’s so much to be discovered. There were so many bursts of creativity, especially in the aesthetic sense, from the 1920s and 1930s, and then another burst from the 1960s to the 1970s. I’m realising that there are very few truly new ideas out there. [There are] some things that I thought were novel – it could be a great case design for a watch that I’ve never seen before – [that turn out to have] been done many times before. I’m in a learning process, rediscovering some of the forgotten vintage pieces out there that most people in the world just may not have spent much time thinking about.

There always seems to be something new to uncover.

I know I’m not the only one thinking this, or by any means a pioneer in this mindset. A lot of amazing collectors that I looked up to have helped me with this path, but I think that’s exciting for me.

Something that I wanted to touch on in our discussion, as we’ve talked a lot about watches and your journey through collecting, is the way you’ve documented this journey. Your watch photography has always stood out in the crowd. Could you tell me a bit about how that has developed?

Back in the day, before I had kids, I had so much time to hang out at cafes with pretty props and pretty lighting, and to take nice pictures outside. Now I’ve got two kids at home and I never really have time to do anything outside, so I’m sort of stuck just taking watch pics next to my bedside table. But I think I’ve learned that there are many ways to present a watch. When I was a movement geek, I would try to go in close and catch all the details and take high-magnification macros. I don’t have the luxury to spend as much time on watch photography as I did before, so I’ve taken a bit of a step back.

It’s always been an integral part of my watch-collecting journey. In the early days we had Timezone and places like that, and [I’d] learn so much from pictures other people post. There just weren’t a whole lot [of pieces like F.P. Journe] out there, so back then I almost felt this duty to acquire and document a lot of these, and show them publicly as much as possible.

You certainly seem to take excellent retrospectives of your journey so far. Do you have any regrets when you look back across everything?

Every time I sold something [laughs]. It’s a tricky one, because I’m not supposed to have regrets, but I guess it’s less of a regret [and more of] a bittersweet feeling. Oftentimes, I wonder what it would have been like [if I’d just held on to those pieces].

“I’m in a learning process, rediscovering some of the forgotten vintage pieces out there that most people in the world just may not have spent much time thinking about.”

The last cycle of selling was driven by two things: one was when I had my first kid. I panicked and I thought I [was] never going to be able to spend time with watches again. I thought [I was] going to have to sell everything – cars, watches – and [I’d] have no time for any of it. I’d be driving a minivan and I’d be a boring suburban dad with nothing but his kids and work. So I had a round of selling then and I picked myself back up again. Then something came up where I had to help my family with some finances, and I figured instead of digging down into my capital I’d just sell some watches instead. And this was literally right before things just had a massive pop, so [it was] bad timing from that perspective, but I’m very proud of what I did back then to help my family. I’m very thankful, too, for them being proud that I was able to do that.

Our thanks to Doo Sik Lew for taking the time to speak to us about his collecting journey and philosophy.