THE LIFE AND CAREER OF GÜNTER BLÜMLEIN

By Simon de Burton

The internet age has helped to turn a few key figures of the watch world, who might once have been recognised only by die-hard enthusiasts, into horological superstars, whose influence transcends their immediate roles.

While such people haven't exactly become household names, their individual success has occasionally seen them catapulted from the pages of specialist publications, websites and the circle of 'those in the know' to a higher plane of influence.

Günter Blümlein became a key figure of the industry, turning around the prospects of three companies, courtesy of IWC.

An obvious example is Jean-Claude Biver, the industry doyen whose genius as a marketeer and reviver of brands has brought him to prominence as a man who clearly knows about business. So much so, that when high-brow UK news station BBC Radio 4 wanted someone to predict the global effects of the unpinning of the Swiss franc in January 2015, it was not to a professor of economics or a treasury adviser that they turned, but to Biver – who spoke eloquently on the subject, non-stop, for the best part of 10 minutes.

Had he been alive today, one Günter Blümlein might well have been approached to give his opinion in a similar way. As it was, he died 20 years ago, at the young age of 58, before the World Wide Web had helped to bring the once esoteric world of Swiss watchmaking into the homes of millions – but to those who were already part of the scene, Blümlein was legend, as one of the main movers behind the revival of not one noble dial name, but three: Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC and, perhaps most famously, A. Lange & Söhne.

Günter Blümlein with Henri-John Belmont, Jaeger-LeCoultre CEO, admiring the newly released Reverso courtesy of Jaeger-LeCoultre.

However, unlike many industry names, Blümlein had no family background in the watch business. He was born in Nuremberg in 1943, during the height of World War 2, meaning he spent his formative years in a city which had lost 6,000 people and had 90 per cent of its buildings destroyed or damaged by relentless Allied bombing raids.

Rebuilding, renewing and developing were therefore key elements of his youth, something that dominated his future work and which may have encouraged him to follow a career in engineering. Soon, that path took him away from the city and into the verdant surroundings of Germany's Black Forest, where Blümlein had his first taste of the watch world, as a member of the team tasked with re-structuring Junghans.

In its early 20th century heyday, Junghans employed 3,000 people and churned-out three million timepieces a year, ranging from traditional Black Forest clocks to high precision chronographs. In 1956, however, it was taken over by munitions firm Diehl, which employed Blümlein to help grow the business into the industry's third most important chronometer maker behind Rolex and Omega.

It was here that Blümlein fell in love with the watch industry, so it might have seemed surprising that he left Junghans in 1980 to work for the automotive instrument manufacturer VDO Schindling – were it not for the fact that VDO had acquired both IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre just two years earlier.

One of the first projects that Blümlein spearheaded at IWC, the reference 3510, courtesy of Hodinkee Shop.

Blümlein, barely 38 years of age, was asked to oversee both companies as boss of a VDO subsidiary called Les Manufactures Horlogeres (LMH). He initially focused on IWC, taking the company by the scruff of the neck in what proved to be his signature, no-nonsense style, and determining to 'put an end to watchmaking boredom.'

His method of doing this was to completely re-focus IWC's aim on a new target customer. Not the 'over 40, traditionally-minded, introverted, understated, fairly-well-off' individuals who, analysts had decreed, typically bought the brand's watches, but younger, wealthier, more thrill-seeking types.

Among the first models to be developed along these lines were those in the Porsche Design range, followed by the original Portofino collection that combined the best traditions of mechanical watchmaking (still under huge threat from quartz, don't forget) which gave a fresh twist to classic styling.

It was Blümlein, too, who set-out to establish IWC's shamelessly masculine bias by instigating marketing campaigns that, towards the end of his era, included advertisements with texts such as: 'Ladies, you ride our Harleys, smoke our Havanas, drink our Glenmorangie. Hands off our IWC' and 'Almost as complicated as a woman. Except it's on time.' While this would be considered tone deaf today, back then, it was seen as a bold approach.

Just a couple of the masculine-toned adverts that Blümlein green lit in his time at the company, courtesy of Ad Patina.

Another of Blümlein's aims was to prove that a small company, such as IWC was back then, could capably challenge the big players, introducing new ideas and generally disrupting the industry. This was something that he achieved relatively early on in his management tenure, with the 1985 introduction of the Da Vinci, the still-remarkable perpetual calendar chronograph wristwatch that was 'future proofed' to show the correct date for a remarkable 500 years.

Its creator was the legendary Kurt Klaus, who recalled the development of the watch and his fondness for Blümlein in a video interview for Revolution magazine: 'It was my idea to produce a perpetual calendar watch and, at the time, we were producing the Porsche design chronograph with a Valijoux movement. He said 'Set the calendar on this, and then we'll have the most complicated watch there is'.'

Not only was the watch exceptional, it was also accessibly priced and therefore of interest to more people – which was all part of Blümlein's strategy to bring IWC to the fore.

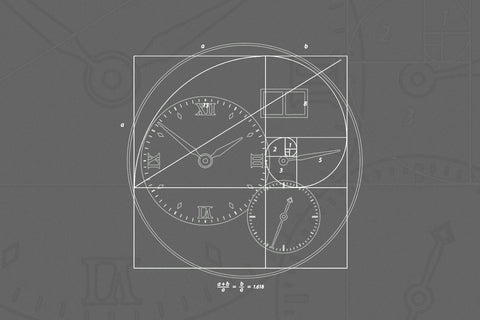

A design sketch for the complex and classically styled Da Vinci, courtesy of IWC.

Famed for his unusual combination of engineering knowledge, avant-garde thinking, hard work and an understanding of people, he could also be a somewhat fearsome individual – but to those who understood him and whom he understood he was, according to Klaus, loyal in the extreme.

'I had a wonderful time working with him at IWC,' recalled Klaus. 'He was the only person who really believed in my idea for a perpetual calendar and, although many people at IWC were afraid to work with him because he was a very strong character, I would say he became my best friend…'

'We would sit in his office and discuss the things he had on his mind. He needed someone to talk about his problems, and we would often be there until his wife called him to come home!'.

It was that granite worth ethic and love for both the watch world and those who worked in it, that made Blümlein such a force in the industry – and, amid the launch of the Da Vinci in 1985, he was handed the reins of the other noble dial name owned by LMH that needed dusting-off and reviving: Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Blümlein didn’t stop at just IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre. Courtesy of A. Lange & Söhne.

For anyone familiar with today's watchmaking landscape, in which both IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre are major, multi-million dollar players with hundreds of employees and impressive, state-of-the-art 'manufactures', it must seem impossible that one man could competently manage both (not least since they were based more than 150 miles apart).

However, the fact that Blümlein could, is not just a reflection of his ability as a manager, but also of just how small such brand names had become as a result of the famous Quartz Crisis.

'We would sit in his office and discuss the things he had on his mind. He needed someone to talk about his problems, and we would often be there until his wife called him to come home!'

Indeed, I remember the late Tina Millar, founder of Sotheby's watch department in the 1960s, suggesting in the early 1990s that I 'keep an eye' on an 'emerging brand called the International Watch Company,' because 'not many people have heard of it.'

Well, Blümlein certainly put an end to that, as he went on to do with Jaeger-LeCoultre which had ridden the 'quartz storm' but still needed some serious rebuilding.

He began by focusing attention on the revival of the celebrated Reverso that, bar a brief moment during the 1960s, had been out of the range since the end of WWII. By the turn of the Millennium, Blümlein had seen to it that the Reverso accounted for 65% of production and had achieved 'icon' status – meaning revenue generated from sales of the various Reverso models enabled him to invest in the development of new, sophisticated watches with complicated movements in order to feed the growing appreciation for traditional horology.

Typical examples of this were the Grand Réveil of 1989, a perpetual calendar alarm watch, the Geographique time zone watch of 1990 and, later, the Master Control series of rigorously tested, ultra-accurate pieces.

“He was the only person who really believed in my idea for a perpetual calendar and, although many people at IWC were afraid to work with him because he was a very strong character, I would say he became my best friend…”

As he had already done at IWC, Blümlein also de-mystified the world of watchmaking by making it far more accessible to customers through factory tours, opening-up to the press and recognising the potential of the internet even before it had properly taken off.

His swansong proved, however, to be the work he did with Walter Lange after the reunification of Germany in October 1990. Between them, the two men set about reviving A. Lange & Söhne, after years of state ownership during which it had been absorbed into the giant, state-owned Glashutte Uhrenbetriebe following its seizure by the state in 1948.

While Blümlein and Lange were the public faces of this relaunch, it was one of Blümlein’s early hires who would prove to be a real difference maker behind the scenes. Reinhard Meis was working for the University of Konstanz as a member of the physics faculty when Blümlein discovered one of his books, Das Tourbillon. Meis, a trained watchmaker, had in fact written multiple books on watchmaking whist conducting research as part of his job at the university. After a long initial meeting, Blümlein hired Meis as a technical adviser and movement designer in 1991. His horological and aesthetic prowess were key to A. Lange & Söhne’s early success, and his fingerprints can still be seen across the brand’s offering. Unfortunately, Meis sadly passed away in January 2023.

It took four years and an estimated €20 million, but Lange and Blümlein's masterful groundwork to re-launch A. Lange & Sohne in October 1994 remains one of the great acts of modern watchmaking history – and his decision to produce a chronograph mechanism entirely in-house from the ground up to create the Datograph proved that Saxon watchmaking was, indeed,more than a match for that of the Swiss.

Günter Blümlein and Walter Lange at the press launch for A. Lange & Söhne, displaying their new four watch collection.

Five years later, in July 1999, Blümlein oversaw the sale of LMH to luxury good giant Richemont for CHF 2.8 billion. And, just 15 months later, those 90-hour working weeks and relentless devotion to the task of making watches great again took its toll.

Blümlein died far too young – and, saddest of all without ever knowing what an indelible mark he would leave on the industry he played such a key role in helping to save.