How the Groups Took Over Swiss Watchmaking

Swiss watchmaking's current status quo includes three big group players, namely Swatch, LVMH, and Richemont. These exist alongside a handful of smaller groups and independent brands, such as Rolex, Patek Philippe or Richard Mille. These three conglomerates are large, even beyond watch industry standards. They're multi-billion dollar entities that are up there with some of the world's largest corporations, from both a revenue and employment standpoint. The tale of how these groups came to be goes back decades. It's a complex and detailed story, which involves transactions on an eye-watering scale.

This process of consolidation has been quite gradual. The first sizeable Swiss watch industry group was formed in 1931 in response to the Great Depression. The takeover of the currently dominant groups, however, can be dated to the 1980s, with some groups forming out of necessity, ambition, or in some cases – being forced to.

Considering they hold such a dominant position in our industry, we wanted to dig a little deeper on the origins of these groups and how they became so powerful in a relatively short space of time.

The Quartz Crisis

The story of the Quartz crisis has been shared more time than we can count. The rise of battery powered movements sent shock waves through the Swiss watch industry. While we may have previously looked at the effects of this on the advent of certain luxury steel sports watches, it also had a much larger structural effect on the Swiss watch community as a whole.

The term crisis isn't an understatement either. It truly devastated the Swiss watchmaking industry, with employment falling from 90,000 in 1970 to 28,000 in 1988. However, like any crisis, there was an opportunity to be found. Large conglomerates and competitors alike saw a chance to pounce on prestigious brands with long legacies and pedigree, stunted by poor cash flow and an ever-growing mountain of debt.

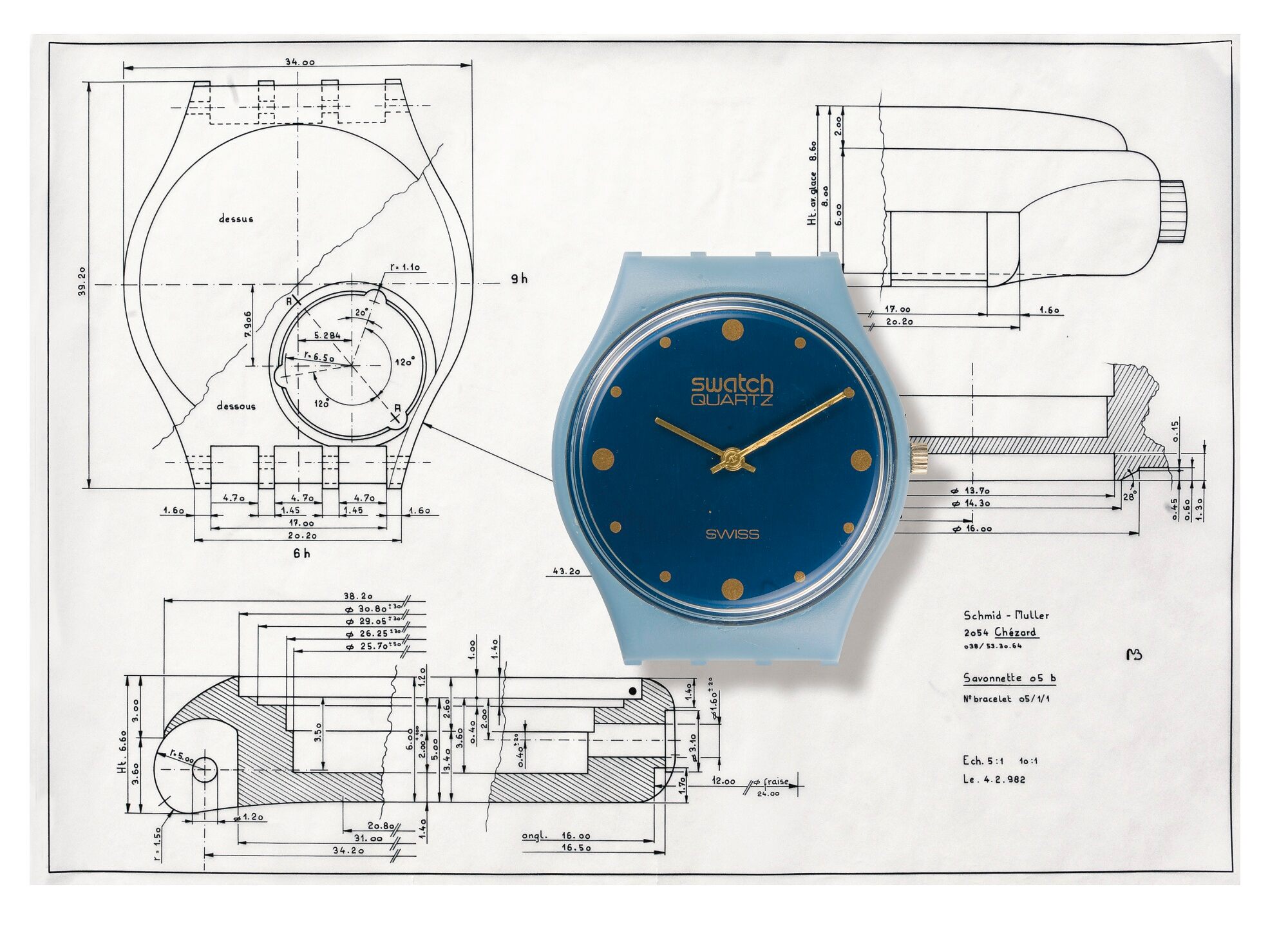

It wasn’t just groups that were a product of the Quartz Crisis, a few memorable watches were made as well.

Of course, these old manufactures were not bought up just for the sake of it. They granted access to crucial markets for younger brands, whilst giving the struggling manufacturers a lifeline. The group approach also makes sharing technology a lot easier, such as the use of Jaeger-LeCoultre movements in Ralph Lauren watches.

Since then, in the last 50 years, we've seen multi-billion dollar cash and stock-for-stock transactions, resulting in enormous parent companies who've risen to industry dominance. Specifically, stock-for-stock mergers have become particularly prominent, where the purchaser pays with their own stock. This is usually more efficient and helps a mutually beneficial outcome.

For example, in 2011, LVMH acquired Italian jewellery brand Bulgari in an "all-share" deal worth $6 billion. The Bulgari family sold their controlling interest in exchange for 3% of LVMH. Wind back to 1999, a simple announcement that TAG Heuer was thinking of accepting a $741 million cash offer from LVMH group for all its shares, caused their share price to rocket 8%. Although a frequent occurrence when an acquisition is announced, it's also indicative that the market expected the deal to have a longer-term positive impact on LVMH's stocks. With that in mind, let's have a closer look at the groups.

Swatch Group SA

Logically, the place to start is with the Swatch Group. Although not the largest group by value, the Swatch Group has arguably the most significant foothold in the watch industry and the most enthralling story to tell. Founded in 1983, Swatch resulted from a merger between two substantial companies, ASUAG and SSIH. Both corporations had a slew of watch brands, and this formation brought together brands like Omega, Tissot, Longines, Hamilton and Oris.

The watch that would prove to be so popular the group would be renamed after it, courtesy of Swatch.

Interestingly, both companies were forced to join by their creditors, the Swiss banks, in 1983, and Société Suisse de Microélectronique & d'Horlogerie (SMH) was born, which was later renamed to the Swatch Group SA in 1998. The renaming happened after the success of the cheap plastic watches that seemed to capture the public’s imagination. This merger was recommended by Nicholas Hayek, who put the idea and plan together and became Chairman and CEO in the process.

Later, in 1985, Hayek acquired a majority stake in SMH at very favourable rates, which gave him the autonomy needed to execute his plans. Widely credited as the man who helped save the Swiss watch industry, Hayek's celebrity lives on to this day.

Hayek can also be credited with a vision of consolidation and automation in the watchmaking world, seeing a huge opportunity to cut overheads and consolidate operations. He was also heavily invested in automating and standardising the manufacturing of watches across the group and, in doing so, unlocking more significant margins and centralising production. Regardless of whether you feel this had a negative or positive impact in the long term, Hayek's impact was sizeable.

The merger was more than a simple restructure of the organisational chaos that was SSIH and ASAUG. Take Omega, which at the time of the merger had over 2,000 individual SKUs across all segments and was on the brink of oblivion. Hayek fought hard to save the storied brand, putting in place new management and a clear strategy.

Two of the key figures behind the rise of the Swatch group, Jean-Claude Biver and Nicolas Hayek, courtesy of Hodinkee.

Hayek's management style and philosophy went against the grain and ensured that the Swiss watch industry was able to thrive through new-age thinking. Hayek saw what others couldn't, the emotion of watches. In a 1993 Harvard Business Review interview with Hayek, he spoke about the crucial importance of emotion in watchmaking:

“I understood that we were not just selling a consumer product or even a branded product. We were selling an emotional product. You wear a watch on your wrist, right against your skin. You have it there for 12 hours a day, maybe 24 hours a day. It can be an important part of your self-image. It doesn't have to be a commodity. It shouldn't be a commodity. I knew that if we could add genuine emotion to the product, and attack the low end with a strong message, we could succeed.”

Hayek's legacy of tight vertical integration extends to the Swatch Group’s manufacturing of movements, from the likes of ETA, and components, which today account for 25% of worldwide production.

In the years since its formation, the Swatch Group SA has made its share of acquisitions. The shopping spree started in 1991 when they purchased Blancpain from Jacques Piguet and Jean-Claude Biver, who rebuilt the brand from nothing after buying it for CHF 22,000 in 1983. The CHF 60 million purchase left Piguet and Biver instant millionaires, with Biver remaining as CEO until 2002. Biver’s addition to the Swatch Group SA was overwhelmingly positive, and he played a pivotal role in repositioning Omega. Biver's legacy at Omega includes the idea to work with Cindy Crawford, and, of course, placing Omega into the James Bond franchise. In doing so, he pioneered the modern idea of a watch brand ambassador.

The next major acquisition was Breguet, in 1999, much to the disappointment of Jean-Claude Biver, who was also eyeing up the iconic brand. HODINKEE's Joe Thompson, who has been covering the Swatch Group for more than 20 years, once reported that Hayek's rumoured intentions when purchasing Breguet was to actually acquire movement manufacturer Nouvelle Lemania, which Breguet owned, rather than Breguet itself. Either way, the purchase secured vital parts for existing Swatch brands. For Hayek, Breguet went on to become the apple of his eye. Thompson also confirmed with Hayek and Biver, Biver's eagerness, and subsequent disappointment, to run Breguet in 1999.

Today, the Swatch Group's operations extend beyond watchmaking and movement manufacturing, with a global Swatch watchmaking school to ensure the craft of watchmaking continues for generations to come.

LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy)

The group was founded in 1988 by Bernard Arnault, who not only controls some of the biggest brands in watches, but also high fashion and beverages as well. LVMH was formed through a merger between Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennesy, with roughly 60 subsidiaries at present, of which just seven are watch brands. Most notably, these are Bulgari, Hublot, TAG Heuer, Zenith and – most recently – Tiffany & Co.

LVMH's rapid expansion into the watch industry began in 1999, when the group purchased a controlling interest in TAG Heuer for $739 million, only 14 years after the TAG Group acquired Heuer. This slew of purchases continued, with LVMH acquiring Zenith that same year for an undisclosed sum, bolstering up manufacturing capacity. Lesser-known brands Ebel and Chaumet were also acquired just months apart.

Bought by LVMH and taken over by Biver, Hublot was transformed by entering into a group.

Rather interestingly, in 1999, LVMH also purchased Phillips Auctioneers to dip their toes into online auctions, albeit an unsuccessful venture on this occasion. After just a few short, expensive years, LVMH sold the majority of its ownership and said farewell to the auction business.

Flash forward to 2008, and LVMH again added to their stable of watch brands, acquiring Hublot from founder Carlo Crocco. With that purchase, then Hublot CEO Jean Claude-Biver - minority shareholder and Board Member - became an employee of LVMH. Irrespective of your thoughts on Hublot, this might just have been one of the best decisions LVMH made – as Jean Claude-Biver went on to lead Hublot as CEO until 2014 when he was promoted to LVMH's president of watches. An industry titan, the undisputed legacy of Jean Claude-Biver's influence and watch-industry insight is well documented.

One of the more recent collaborations to come out of Bulgari with architect, Tadao Ando.

In more recent times, LVMH settled a deal to purchase Tiffany & Co for an insurmountable $16.2 billion dollars. This was noteworthy not for its watchmaking, though there is certainly scope and potential, but the sheer size of such a purchase. Not to mention the coveted watches that are sold in its stores.

Richemont

Lastly, we look briefly at Richemont, one of the largest companies on the Swiss Market Index. Founded by Johann Rupert in 1988, Richemont was essentially a spin-off of the existing family business, with a dedicated focus on luxury goods.

In a series of complex acquisitions and holdings, between 1988 and 1989, Richemont acquired a majority stake in Rothams group, which encompassed Cartier, Montblanc, Baume & Mercier, Piaget, and several other luxury brands.

In comparison to the Swatch Group and LVMH, Richemont's appetite for acquisitions was much stronger. In the 1990's they acquired both Vacheron Constantin (1996) and Panerai (1997). Just years later, in 2000, Richemont acquired Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC and A. Lange & Söhne, before purchasing Fabrique D'Horlogerie Minerva SA in 2006, securing some long-standing manufacturing prowess. Minerva was a tiny company with just 22 employees at the time. They specialised in the development and manufacturing of high-end mechanical movements. This purchase ultimately led to a partnership with Montblanc.

Buying Minerva was one of the last pieces to Richemont’s watchmaking puzzle, courtesy of Hodinkee.

Also, in 2006, they announced a relationship with a 20% holding in Greubel Forsey, just two years after the brand was formed. A year later, a joint venture with Polo Ralph Lauren led to the formation of the Ralph Lauren Watch and Jewellery Company. Richemont later acquired the component manufacturing operations of Manufacture Roger Dubuis SA, known now as Manufacture Genevoise de Haute Horlogerie, or more commonly MGHH. In 2007, Richemont also purchased a case manufacturer – Donzé-Baume SA, and then 2008, a controlling stake of watch manufacturer Roger Dubuis.

Things get particularly interesting in 2010 when the group acquired the majority of online fashion retailer Net-A-Porter as a complementary entity. Both Mr Porter and Net-A-Porter sell online luxury watches alongside luxury fashion brands like Gucci, Balenciaga, and Celine, to their established customer base. This move allowed Richemont the perfect platform for online retail, at a time many other brands were still wrapping their head around Facebook.

Net-a-Porter opened up the world of ecommerce for Richemont and all of its brands, courtesy of Mr. Porter.

More recently, in 2018, Richemont acquired Watchfinder Limited – which again gave them a significant revenue boost, and access to a pre-owned luxury watch marketplace, closing the loop in a sense.

Out of every crisis comes the opportunity to be reborn

The groups of Swiss watchmaking might be relatively young in the grand scheme of horology, yet their impact has been undeniable. Not only has their formation helped to preserve old manufactures that had seen better days, but they also helped breathe new life into an industry that had just been shaken to its very core.

While these groups are now massive entities that cover the globe, we can see that there have been a few key players that have made a real difference in their trajectory. Today, these conglomerates play a more vital role than ever in the world of watchmaking, as they ensure the continuation of the history that we all cherish and help bring horology to more people than ever before.

As for what the future holds, well, if the past is any indicator, we can expect these brands to continue to grow their retail and online presence, for both new and pre-owned. These acquisitions will continue, and the groups will continue to increase their global footprints when the opportunities arise. Whether the recent disruption the world has gone through will result in more cooperation in our industry or a fracturing, only time will tell.