What Makes Gratté Finishing So Special?

Kwan Ann Tan

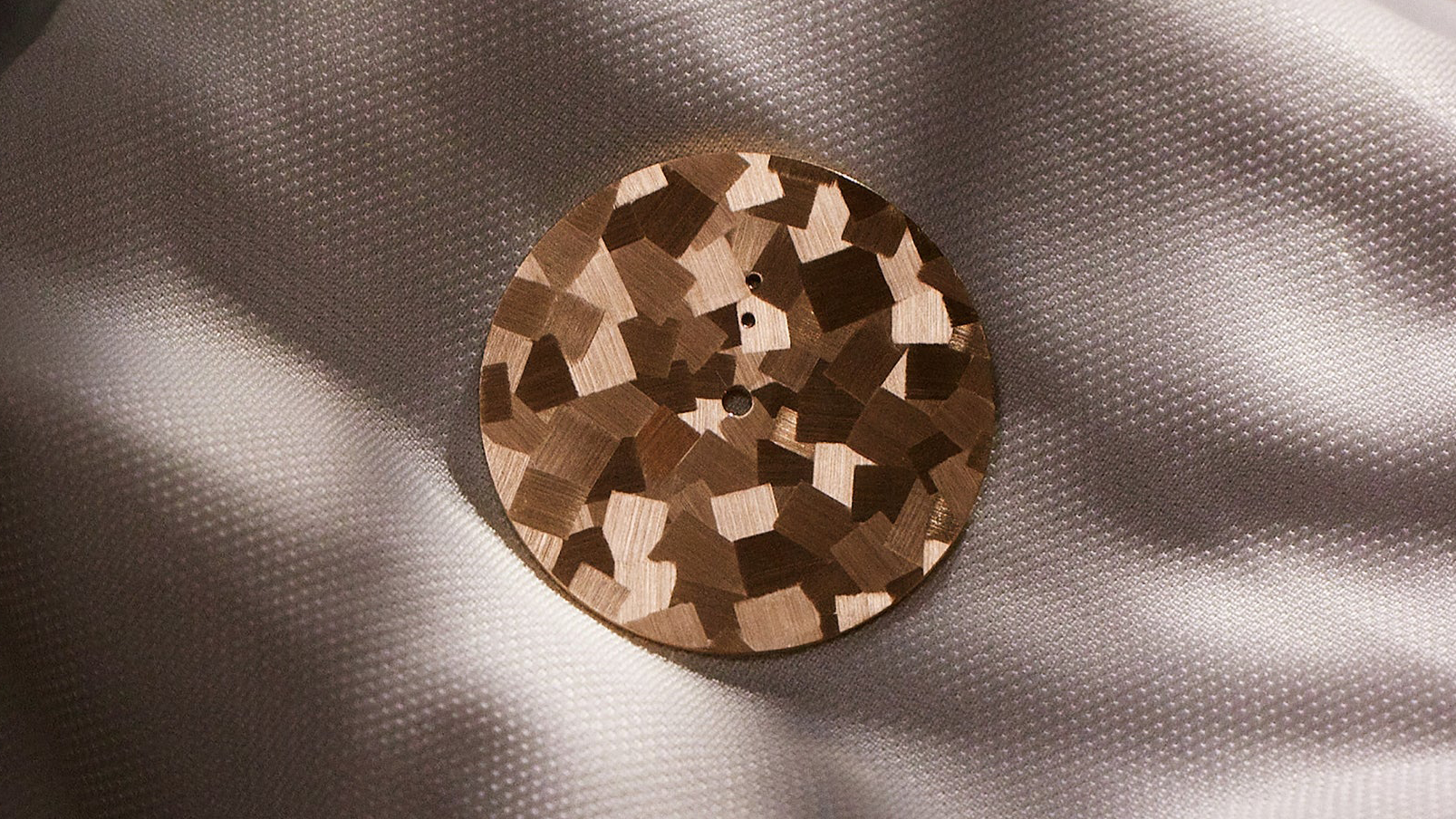

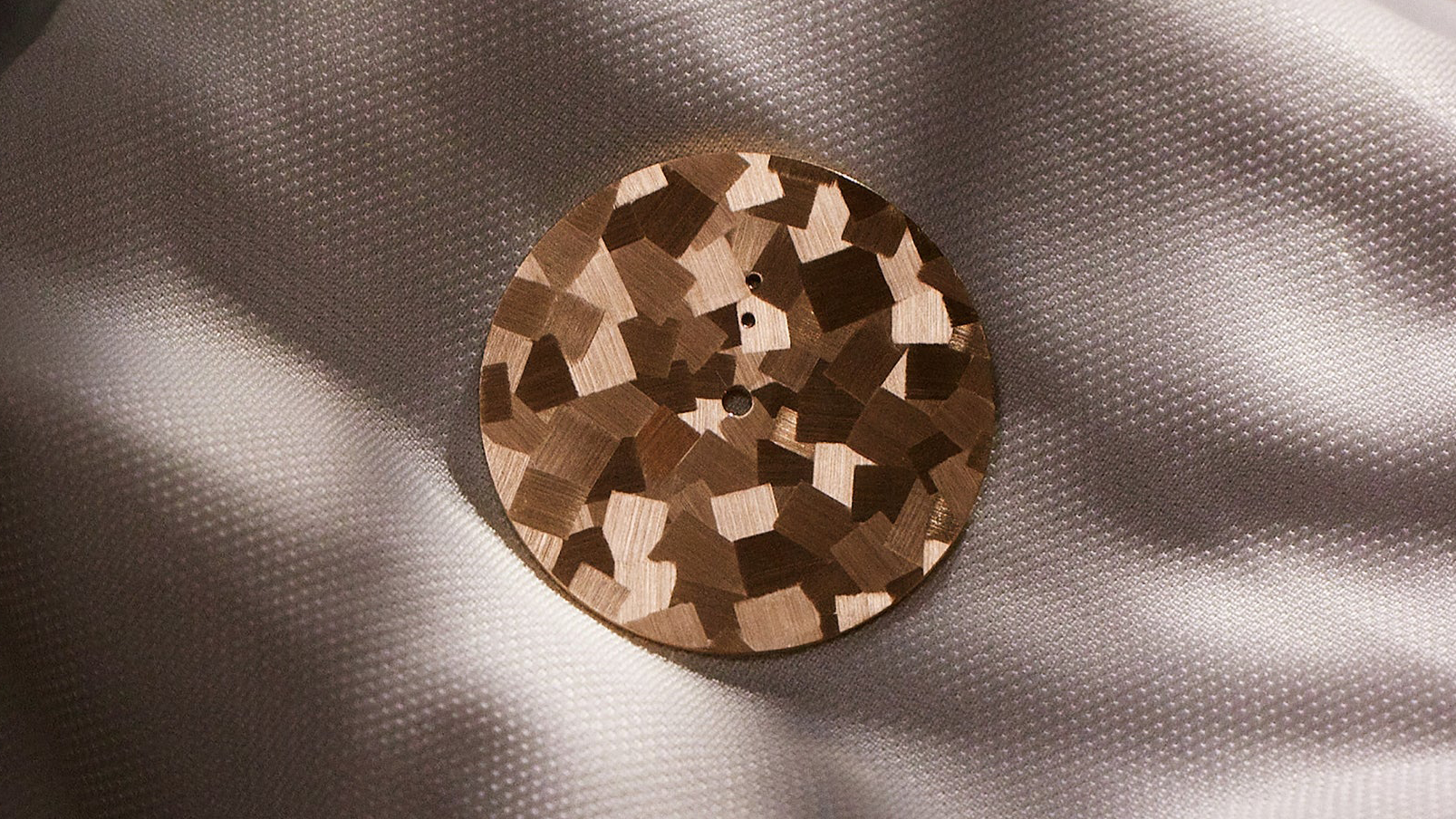

When you first glance at the dial, your eyes can’t quite distinguish its texture. Under the light, different points glint, overlapping to create a striking mosaic effect. Some have a harder, more precise texture, while others are softer, blurred in an Impressionist manner. Known as “gratté finishing”, this type of decoration is a rarely seen technique in the mainstream, with most of the watches featuring it coming from independent makers, as the craft required for each dial would be impossible to recreate at scale while retaining the same effect.

The process as we know it today was first developed by Greubel Forsey for the Hand Made 1, visible on the mainplate of the watch’s movement, through its sapphire caseback. Similarly, the decoration can be found on the reverse of watch dials created by Winnerl, such as within the Tremblage; on the movement of a unique piece from Théo Auffret. When Petermann Bédat chose to use this finishing in their unique 1967 Deadbeat Seconds, it was a texture they had long been considering, since they had a watchmaker who had previously worked at Greubel Forsey and was familiar with the technique required.

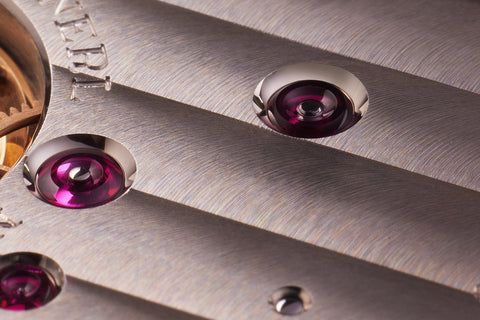

This type of finish has actually been transformed from a traditional type of finish used on machines and lathes, which is done to achieve an even surface. According to Theo Auffret, “The gratté has roots in machine work, and is typically used to achieve perfect geometry on the machines. The finish’s surface is quite porous, so it helps the oil stay in place and ensures good lubrication. It’s a type of finish quite similar to ‘charbonnage’ and the decorative styles typical of school clocks from late 19th-century Paris. Some ‘charbonnages’ were smoked, while others were much more geometric – for example, in ovals, ripples, or checkerboard patterns.”

The surface of the plate must first be softened, through fine circular brushing technique called “brouillage” in French. Then, the watchmaker prepares a piece of wood known as a cabron, using a knife to shape it, then attaching a tiny piece of sandpaper the size of 20 micron to the tip. They use the cabron to mark the plate, creating blocky strokes that layer over each other and have a similar appearance to brushstrokes, then go back and forth across the whole dial from different angles and approaches to create the most striking contrast.

In the case of the unique 1967 Deadbeat Seconds, the watchmaker starts creating these strokes from the outside, slowly moving towards the centre. According to Gaël Petermann, “To keep the texture even and to ensure a perfect layer it’s down to the sensibility of the watchmaker and their ability to see how the metal reacts. The main goal is to be consistent during the whole process and apply the right pressure, that’s why it took us a very long time to achieve this finishing.”

Gaël Petermann

The gratté finishing is a delicate backdrop to the Eastern Arabic numerals found on the dial, giving a sense of depth and texture.

Naturally, creating the complex pattern on the dial is the most challenging part, as every aspect has to be carefully calibrated. Finding the right roughness for the cabron in order to get the right balance and achieve the densely packed brushstroke effect is crucial, as every mark must look identical. “Getting something homogeneous is difficult,” Petermann explains.

The result is a carefully calibrated piece of art, despite its seemingly effortless appearance. Both the process and its final appearance speak to the advancement of craft in watchmaking, not just mechanics. Discovering new forms of finishing and developing new formats which add to the deeply varied world of independent watchmaking.

Our thanks to Petermann Bédat and Théo Auffret for delving into the details of this finishing with us.