In Depth: The Story of the "Dirty Dozen" - The First Wristwatches Specially Commissioned for the British Army

We all love military watches. It’s hard not to with the romance of a wristwatch bearing the scars of war and painted with the patina of a time long past. As a relic of a previous life, it is easy to let our imaginations run wild with what the watch has been through, and frankly, I love that.

I am certainly one who basks in the nostalgia of a time of utility, where the purpose of a wristwatch was pure. It seems the honesty of the design is something we can all relate to, and for that it commands my respect. A Universal Geneve Compax with a telemeter used by an artillery officer? Yes please. A 5517 MilSub issued to the Royal Navy? Where do I line up?

Perhaps it is the vicarious nature of these objects that so tickles our fancy, allowing us to step into the wrist, so to speak, of those who wore them before us. After all, isn’t our choice of watch, often, simply a reflection of how we see ourselves?

It is therefore, with great pleasure that I open up this new series for WATCH LIFE, where this week, we fittingly look into the first wristwatches specifically designed for British Army service. A group of military watches affectionately known as ‘The Dirty Dozen’.

So, lets go through the basics first. In the 40s, during World War II, Britain’s Ministry of Defence (MoD) needed watches to issue to army personnel – they felt civilian watches just didn’t quite make the mark. Perhaps in a bid to maximise production, rather than partnering with a specific brand, they invited any Swiss manufacturer who could build a watch to the requested standard, to do so. Well nearly any, but we’ll get to that later…

Due to the rigours of military life, very strict specifications were set, and all in, twelve watch manufacturers were eventually accepted, resulting in the nickname ‘The Dirty Dozen’. They were: Buren, Cyma, Eterna, Grana, Jaeger Le-Coultre, Lemania, Longines, IWC, Omega, Record, Timor and Vertex. These were all delivered in 1945 and accompanied by a pigskin or canvas strap. Remember guys, while these look fantastic with a NATO strap on, those didn’t exist before the 70s!

Military Specifications

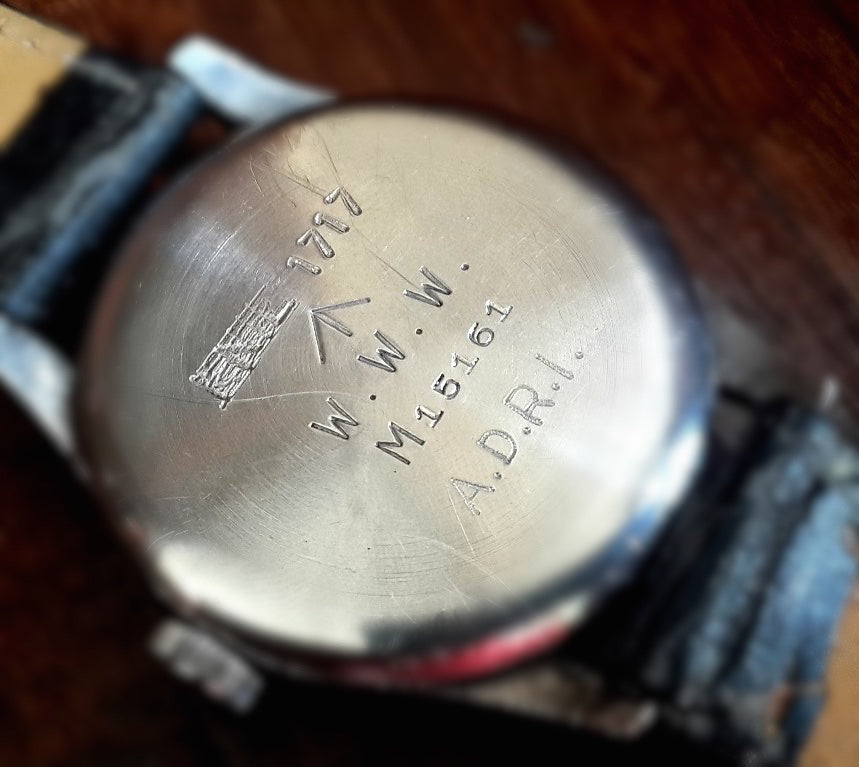

More formally, these watches were known as W.W.Ws, a code established by the British Army to distinguish these from other military equipment and it simply stood for Watch. Wrist. Waterproof. It doesn’t get any more utilitarian than that!

The MoD specs were exactly what you would expect a military watch to be - waterproof, luminous, regulated to chronometer level and composed of a case that was rugged. Two serial numbers were required, one being the manufacturer’s number, and the other (with the letter) being the military store number. On top of that, the dial needed to be black, with arabic numerals and sub seconds in order to maximise legibility. The case-back had to include the W.W.W designation and a broad arrow marking, with the dial only displaying the latter. The broad arrow frequently seen on military dials and case backs, is the traditional marking for Crown property.

Switzerland over Britain

It is interesting to note that the MoD’s choice was to seek watches in Switzerland rather than at home, as Britain’s watchmaking industry had deteriorated considerably by that point. It was not so long ago that the British Isles were a haven for mechanical watchmaking. Think of what quartz did to the Swiss watch industry in the 70s and you have an idea of what a failure to adapt to mass production, did to British watchmaking in the 19th century. Furthermore, the remaining British watch manufacturers had very much turned to making naval and aviation instruments for the war, and so it was Switzerland’s neutrality that allowed their watchmakers to continue to operate.

There is something unusual that really interests me. It is well known that the MoD received W.W.Ws from twelve Swiss manufacturers, but records show that they sent orders to thirteen. The thirteenth was a little known brand called Enicar. Each manufacturer was assigned a specific store number with Enicar designated no.10025, yet there are no known examples. Due to poor record keeping at the time, it is hard to determine what really happened, but rumour has it that the Allies investigated several Swiss companies and found that Enicar was supplying the enemy, and subsequently black listed them!

The whole dozen

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and today, these watches are highly sought-after by collectors. In particular, the ambition of acquiring all twelve has become a grail-like quest, as finding one is relatively easy, but all twelve? Good luck!

I have known collectors spend years diligently scouring the internet for these, just to complete their set, and still fall short. This is by no means a discouragement from trying, instead an advanced notice: It will be a test of your patience and research, but it will only make owning the whole “dirty dozen” that much more satisfying.

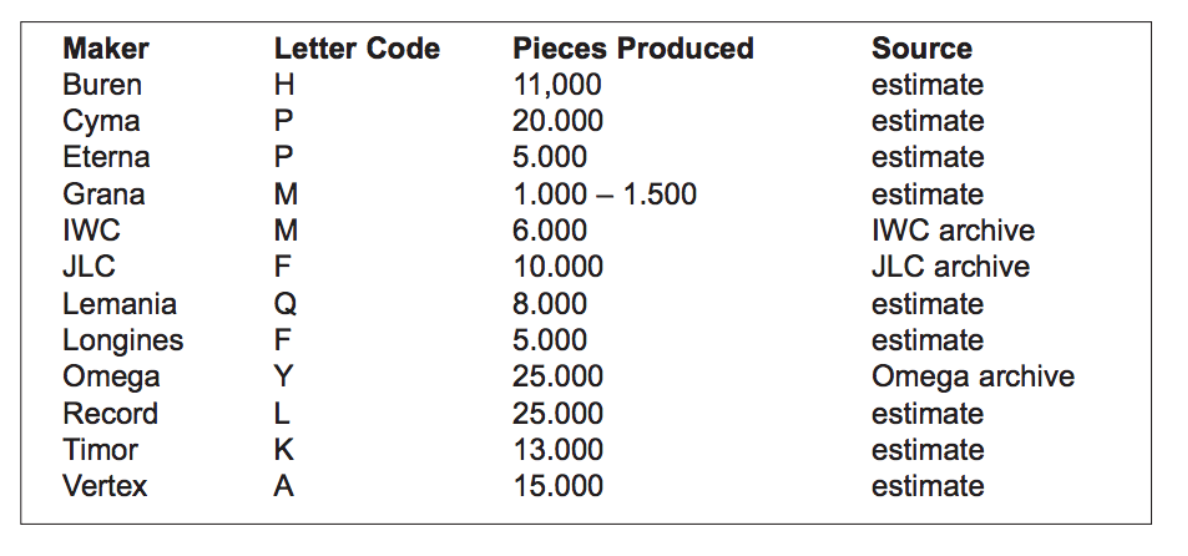

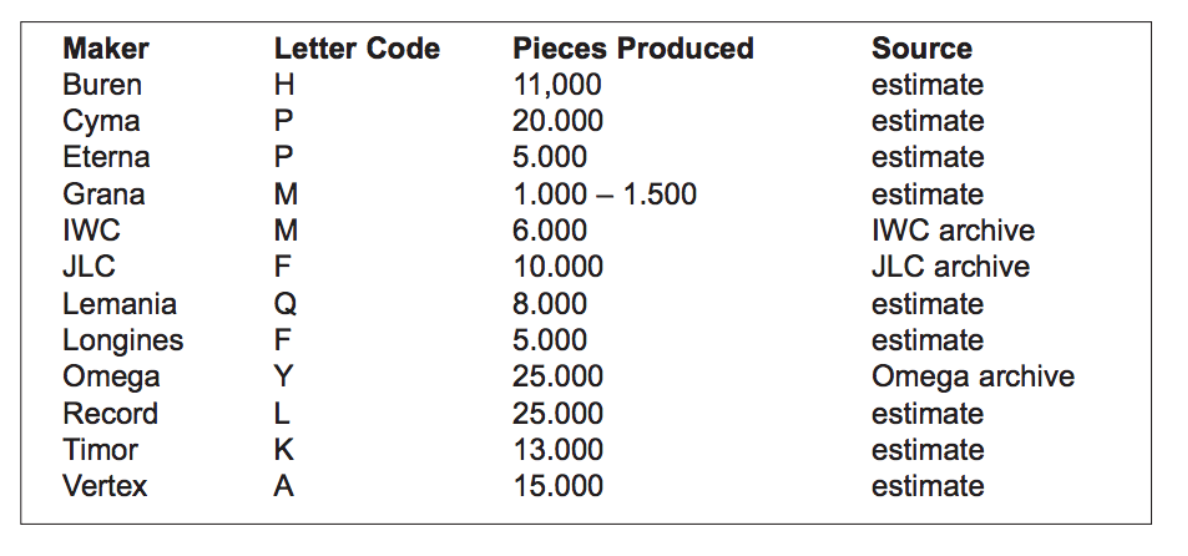

W.W.Ws are by no means rare, as rough estimates say that around 145,000 of these were produced and delivered in 1945, but each company produced a different number, which explains why it is so hard to complete the set. On top of that, it is believed that a lot of these W.W.Ws were destroyed in the 1970s due to the presence of radioactive Radium-226, in the luminescent material. The table below shows the estimated production volumes for each manufacturer and while a simple Google search will allow you to buy most of these - try finding a Grana!

From Konrad Knirim’s book “British Military Timepieces”

Whilst the IWC arguably has the nicest movement of the lot, it’s the Grana’s rarity, that pips it to the post. As the most coveted and expensive of the Dirty Dozen – it is often the one missing from a collection. If you do ever come across one, know that they are extremely rare! On the topic of IWC (as a side note) whilst the dozen were remarkably similar due to the strict specifications, one of the bigger variances is found on the IWC. If anyone is hunting for these watches, take note that they were the only manufacturer to use a snap on case back, while everyone else used screw-ons. IWC was the only manufacturer using a conventional crystal, with everyone else adopting flanged crystals with a screw-in retention ring.

Top to bottom: The IWC 83 calibre compared to the Grana KF320 calibre.

That being said, if I were to take a pick, I would choose the Longines. At 37.5 mm, it remains a great modern size and with its stepped case, larger minute track, the details on this watch are far more accentuated and beautifully proportionate - not to mention the legendary 12.68Z movement!

Extra Notes and a special few...

Whilst it’s clear why, just on scarcity, the Grana is the most coveted of the twelve watches issued, as always, it’s the nuances that collectors love, and boy is there one with the “Dirty Dozen”.

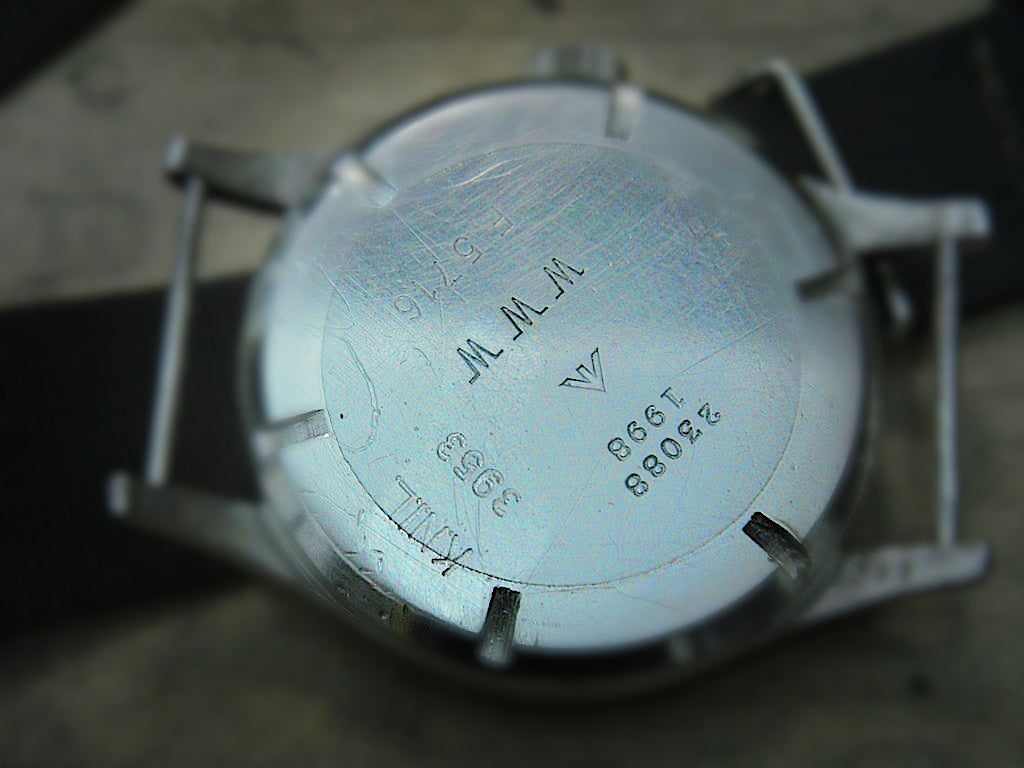

Recognised by their K.N.I.L. engraved case backs [1], these are perhaps the rarest of the “dirty dozen” with less than 10 pieces documented so far. The K.N.I.L. were part of the Dutch army stationed in the East Indies during their occupation.

A reissued Longines W.W.W. with a K.N.I.L. case back.

The story goes, that as these watches were only delivered towards the tail-end of WWII, Britain was left with a significant surplus when the war ended and was keen to get rid of some. While they were celebrating victory on the other side of the world in the East Indies (modern day Indonesia), the K.N.I.L. army, fresh from defeating the Japanese occupation in the region, was back in conflict with the Indonesian freedom fighters who had declared independence. With a need for military goods, the Dutch looked to Britain. Despite being allies, there was a reluctance to sell to the Netherlands, as Britain didn’t support the conflict.. However, providing military watches seemed like a harmless concession and so was allowed, resulting in what is known today as the mythical reissued W.W.W’s with K.N.I.L. case backs.

But wait, the story goes deeper! What is even cooler, is that these reissued W.W.W’s were then re-reissued, again, and this time to the A.D.R.I. (Army of the Republic of Indonesia). These two armies were in conflict, which means that it could very well have been that the watch exchanged hands forcefully. You can see on the case back that K.N.I.L. has been scratched off, quite violently if I may say so, and instead A.D.R.I. engraved. What you end up with is a watch with military history in the British, Dutch and Indonesian armies! If you are talking about provenance, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Notice the top of the case back roughly scratched. A re-reissued IWC W.W.W. with the K.N.I.L. on the case back scratched off and engraved with A.D.R.I.

A final word

There is an endless debate regarding the originality of parts and pieces of these watches as they were often changed during service. Because all W.W.W’s were maintained and repaired by the R.E.M.E (Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers), it seems it was common practice to chop and change watch parts without regard for each specific manufacturer.

Spare hands for Longines in the round case, identifiable through the label stating its stores number of 10032.

On top of that, dials were often replaced by the army, sometimes later on to a tritium or promethium (cheaper variant of tritium) dial or with no brand name (just serial numbers). These dials replaced by the R.E.M.E are known as either MoD or NATO dials, depending on the dial inscriptions and period, inadvertently giving way to a whole host of variances within the dozen. Remember, at the time, it wasn’t about originality and collectability but about function. That, coupled with the lack of record keeping, it is only through compiling and documenting the existing watches that collectors are able to determine what is deemed to be original.

There are many nuances that can be discussed, but if you are interested, check these guys out as they have done an amazing job and compiled images of user submitted W.W.W’s and all of its variances for your reference.

As with any vintage watch, it can be a confusing market, but if you are careful and brave, this can be highly rewarding. Anyway, I hope you enjoyed this article as much as I enjoyed writing it, and if I have spurred even the tiniest of interest in you for ‘The Dirty Dozen’, then I have done my job!

NATO replacement dials, with tritium (T) as a luminous material instead and no brand name.

Special Thanks

I would like to say a very special thank you to Siewming who very generously shared his Dirty Dozen and allowed us to use it for this article. All the watches seen in this article belong to him, except the K.N.I.L. and A.D.R.I. watches. Not only that, all the spare parts and the VERY rare IWC delivery box are his. His guidance in researching this story is also greatly appreciated. Ownership and all rights to the pictures remain with him.

FOOT NOTES:

[1] Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger or Royal Dutch Army of the East Indies