The blending of technology and tradition in the watch world

Benoit Mintiens thought long and hard before deciding to put an electronic component into his Type 2 watch, the concept version of which launched a couple of years ago. Here was a £38,000 watch with its e-Crown, which linked it to your smartphone, so the time is spot-on whenever you go to put it on. At that price, the founder/designer behind Ressence pondered, watch fans don’t typically want components that are not easily replaced, or which require batteries.

“And, what’s more, I know that the batteries we use in that watch for sure won’t exist in maybe 10 years time,” he says. “We can’t even be sure we’ll be using smart-phones in decades to come. So we’re involved in the blending of two worlds – the mechanical, which has worked well for centuries, largely unchanged, and which would keep doing so for centuries more – and the technological. And I deliberated hard because I didn’t want the watch to become obsolete. But big new, disruptive ideas do come along.”

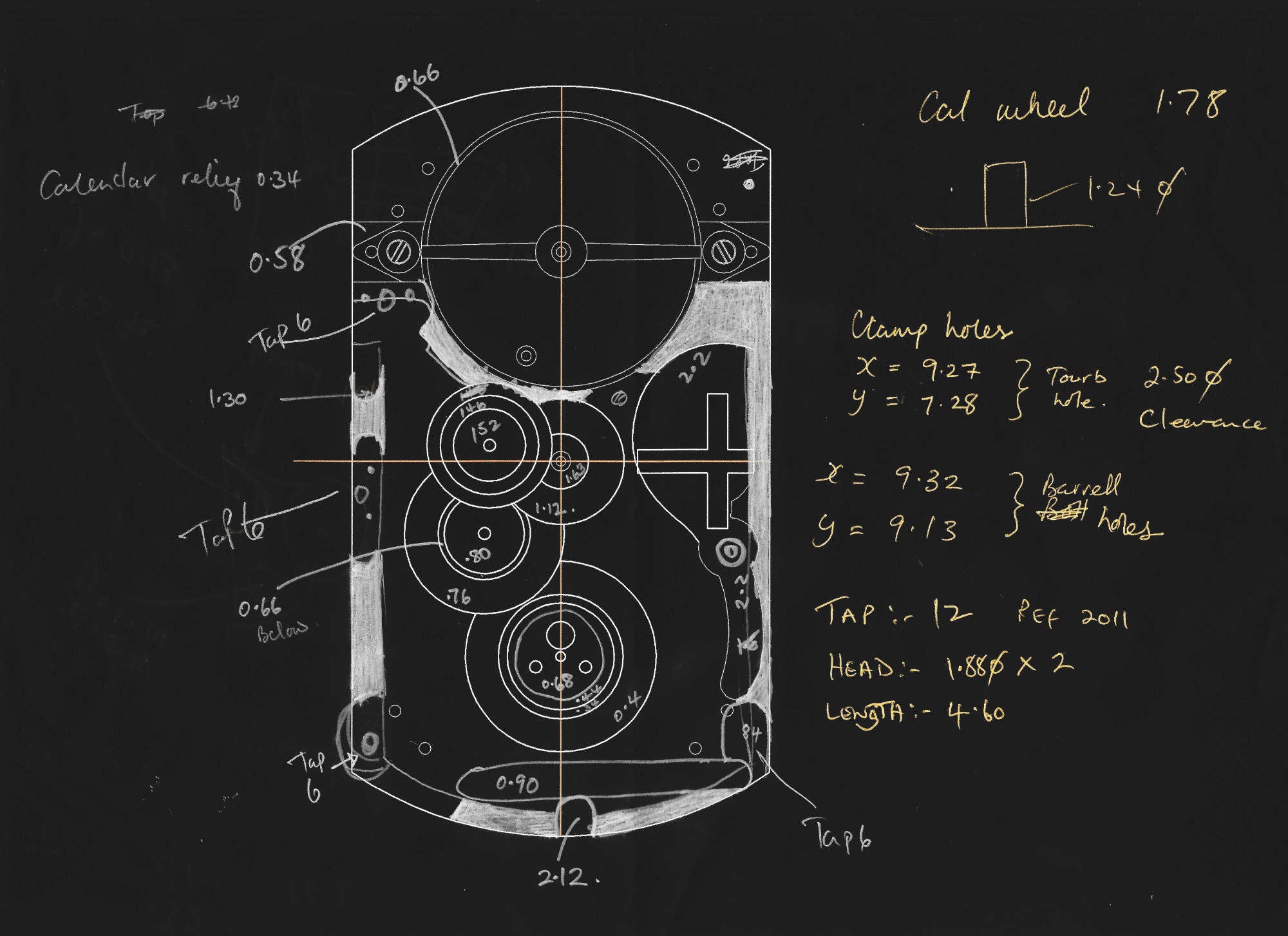

A technical drawing for George Daniels' Blue wristwatch.

Indeed, with a boom in our understanding of metallurgy and materials science, with ever more advanced computer-guided machinery capable of working at ever finer tolerances, it’s small wonder that there are high-end watches today that would astound a watchmaker of just a few decades ago. The watch world has always made small advances. But now it is seeing an interweaving of the traditional and the futuristic at a breakneck, if thrilling, pace.

“No wonder people are often confused by the seeming conflict between cutting-edge design and old-school materials, between the use of very new and very old methods in the same piece,” reckons Max Busser, founder of MB&F, with a sapphire top-plate and a watertight 3D gasket, among MB&F innovations. “It’s the conflict between the conception of watch manufacture as a high-tech, sterile laboratory, and the conception of it as being done by some old guy with a loupe at a bench in an Alpine chalet. Neither are right.”

Two of MB&F's more inventive pieces, the HM5 and LM101.

It’s why Mintiens defines fine watchmaking on the grounds that, however advanced it may be, in materials or methodologies it’s also designed so as to not become obsolete. That’s why his Type2 e-Crown not only functions without a smartphone, but also why its battery compartment is built into a chassis designed to be adaptable to batteries yet to come.

“It’s the smartphone, in fact, that is encouraging discussions regarding the future of the contemporary mechanical watch – the notion it has to offer some new perspective,” argues Gregory Dourde, CEO of HYT, which has recently launched a watch which allows energy stored in a mechanical micro-generator to illuminate a cluster of tiny LEDs, and hence the whole dial. “I think of our job as not being just to make improvements to the 18th century technology still being used across the industry – because I’m really not sure that improving a watch’s accuracy by one-tenth of a second each time is going to work for a lot of people over the next 20 years – but to bring completely new ideas, within a mechanical setting.”

The HYT Flow, the company's latest high-tech release.

Call it contemporary with a classical failsafe. Even Roger Smith, one of the greatest watchmakers of his generation, who one might imagine to be a traditionalist through and through, is now working with Manchester Metropolitan University to deliver a nano-tech coating to dry lubricate watch parts at the atomic scale.

“Certainly some people raise their eyebrows when they hear such a traditional watchmaker is doing this kind of thing,” laughs Smith, “but we’re also careful that this tech doesn’t affect the core of the watchmaking at all. Even if the coating only lasts, say, 30 years, the movement will continue to work with more traditional lubrication."

"I do think there are occasions when the introduction of a new tech to watchmaking is more about marketing. The escapement is already inefficient. Adding silicon, for example, just masks the fact. But we’re not Luddites. We have to be open to new ways of improving functionality, or durability.”

The Daniels Blue, created using only the most traditional of methods but made to last a lifetime.

“The worlds of tradition and technology in watches overlap continuously now. You can’t make any high-end watch – however futuristic it may look – without traditional methods,” says Theodore Diehl, horologist for Richard Mille. “There are aspects to our watches that are avant-garde, but at heart they’re quite conservative, mostly within the realm of metallics parts which will definitely be repairable or replaceable at any time in the future. There are some materials we would use – based on carbon, metalloids, ceramics – yet others we wouldn’t use – silicon, for example, because the future of silicon parts is uncertain.”

“It’s the conflict between the conception of watch manufacture as a high-tech, sterile laboratory, and the conception of it as being done by some old guy with a loupe at a bench in an Alpine chalet. Neither are right.”

- Max Busser, MB&F

But, he concedes, there is perhaps some kind of displacement going on, as bold, high-tech advances in watchmaking replace the tried-and-tested (which, naturally, were once high-tech themselves). Akin to the ethical question facing bio-engineering – how much of the human anatomy can you enhance before the being is no longer human? – maybe the question is how many incremental steps in the development of mechanical watchmaking can you make before a watch is no longer within the emotional, historic, cherished traditions of watchmaking?

Richard Mille's inventive designs at play, courtesy of Revolution.

The fact is that new materials are in development all the time – typically for other uses, then borrowed by the watch industry for some functional benefit – and so is the machinery used for making watches. “Machinery like 3D printers, multi-axis milling and turning machines, they all allow watch manufacturers to do what wasn’t possible just 10 or 15 years ago. And that developmental pace is picking up. You can produce components that were unimaginable back then,” says Walter Volpers, associate director of technics at IWC. “And yet then the industry is still using technology that’s a century or more old – preserving energy in a mechanical watch is still best done with a spring in a barrel, even if there’s a lot of money and research going into finding the next generation of that idea.”

And yet just because there is a new technology that could be introduced into a watch, it doesn’t follow that you should. Economics might get in the way. “There’s always industrialisation to consider – a new watch technology has to work at scale,” stresses Volpers, who oversaw the introduction of IWC’s use of ceramic oxide components to reduce wear and tear in winding mechanisms, and the five year study that resulted in the use of Ceratanium, a titanium/ceramic hybrid, light and strong but also scratch-resistant.

“We wouldn’t introduce a new technology until we knew we could scale it up – and we’ve had lots of innovations that we’ve had to stop for that reason,” adds Volpers. “It’s a tough decision and it can be annoying – but you go to management and say we can do it for one or two million more and they say ‘no way!’, because it doesn’t make business sense.”

Inside the IWC manufacture where they have integrated some of the latest technology to assist in the watchmaking process.

Even when it does make business sense – in terms of unit costs, pricing and profit – it may still not make business sense. Take the instance of Roger Dubuis, for example. Nicola Andreatta, the company’s CEO, notes that its remit is all about pushing at the edges of what’s possible in watchmaking - “if [its late founder] Roger had wanted to keep working in the world of classical watchmaking he’d have probably just stayed at Patek Philippe,” Andreatta notes, “not that Patek doesn’t still do incredible things”. But he adds also that it can do this in part because Roger Dubuis makes its watches in such small numbers, often as one-offs, typically in editions of just a couple of dozen or so.

But this doesn’t mean it will push at those edges at every opportunity. Why? Because it’s more important to Roger Dubuis that its watches carry the Poincon de Geneve – the Geneva Seal, a certification issued by the Watchmaking School of Geneva, which has to sign off on every technical advance the watch brands that carry its seal propose.

Two Geneva Seal movements - one from Patek Philippe, the other from Roger Dubuis - proving change doesn't doesn't have to mean rejection of tradition.

“While we want to explore the evolution of watch design we’re also strongly linked to tradition,” explains Andreatta. “And the Poincon de Geneve is limiting. When we did our first full carbon fibre movement, for example, or used a different material for the gong in a minute repeater, we had to present that to them. And there are other ideas we know won’t be compliant [with their vision of watchmaking]. We either have to try to change the rules they apply or, from time to time, just drop the idea. The seal is that important to us. It can sound like a marketing gimmick, but it’s indicative of watchmaking at another level.”

“Certainly some people raise their eyebrows when they hear such a traditional watchmaker is doing this kind of thing"

- Roger Smith

Indeed, while some advances in watchmaking materials or methodology make for good PR, getting the message of said advances in materials or methodology across to customers is not so easy – in part because the science can be complicated, and not least because, typically, they can’t actually see anything, short of breathing over the shoulder of a watch technician as they carry out a service.

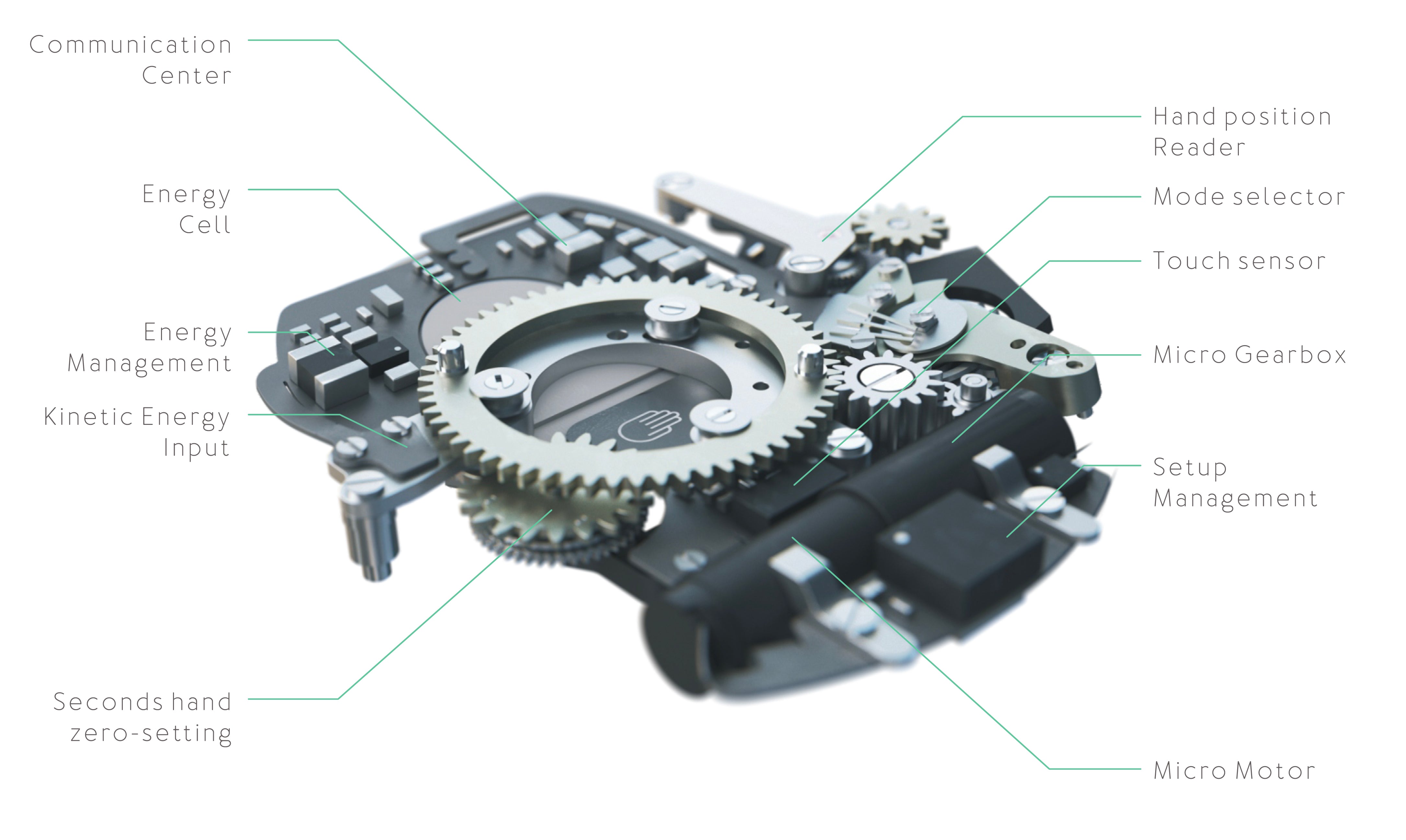

What goes into the Ressence e-Crown.

“You can have a watch, the design of which is still well within tradition, but the mechanics are extremely progressive, and that’s hard to get across,” explains Volpers. “But I think consumers are more and more buying watches for what’s on the inside, especially as they become more knowledgeable about watchmaking.

Of course, they also like to understand quite why they may be paying more for a watch – that it’s the use of new lightweight materials, or even a material rarely found in watchmaking, like aluminium, that allows a watch to use minimal energy to turn the discs of a big date complication, for example.”

Image does matter too. A new technology might be useable in a certain model, and might even give that model a distinct functional improvement. But the technology still has to feel right for that model; it has to chime with its story. It’s for this reason that, Volpers explains, you won’t necessarily get the new stuff in such a classic piece as its Portugieser. “You always have to bring the properties of a new material into context,” he says. “Ceratanium just wouldn’t be right given the romantic, maritime heritage of the Portugieser. A new tech still has to match the story of the watch it goes into.”

Ceratanium in the production and testing phases at IWC.

Feelings like this are hard to pin down, but it’s easy to see what he’s driving at, even if it buts up against our dubious 21st century conception of technology as being an unmitigated good – always indicative of enhancement, improvement and progress, always better to have and use than not. But, no, not always. Diehl draws an amusing parallel between the option to have a dog and to have a Sony Aibo robot dog, which doesn’t moult, yap or defecate on the carpet. The latter is in ways better. The former speaks to the soul.

And that's what mechanical watches are about. Martin Frei, co-founder of Urwerk – certainly one of the Swiss industry’s more progressive makers, both in terms of aesthetic and technology – makes the philosophical point that pretty much any advancement in materials or methodology in mechanical watchmaking is moot, since any mechanical watch, as a means of telling the time, is almost by definition outmoded in a digital age.

The futuristically designed Urwerk UR-102.

“I’ve got nothing against a tourbillon, for example – it’s a beautiful piece of engineering, but it was developed to make marine chronometers more precise and the argument has to be that as soon as new technology came up, which it did, the very idea of the tourbillon was out of date,” he says. “And the fact is that if the world around an object changes – as with cars today [in relation to congestion, pollution etc.] and yes, as with watches – then the object must change too.

“This debate about the balance between tradition and technology in watchmaking is really a re-framing what the wrist-watch is all about,” Frei adds. “If you stop thinking about it purely in terms of function, it gets a different, second life more as a beautiful object. It’s liberated, if you like. Artists still use the earliest techniques of art, right back to cave paintings, but they also work with the most contemporary technologies. So why not watchmakers too? Yes, maybe we’ve reached a point where watches need to be thought of more as pieces of art.”